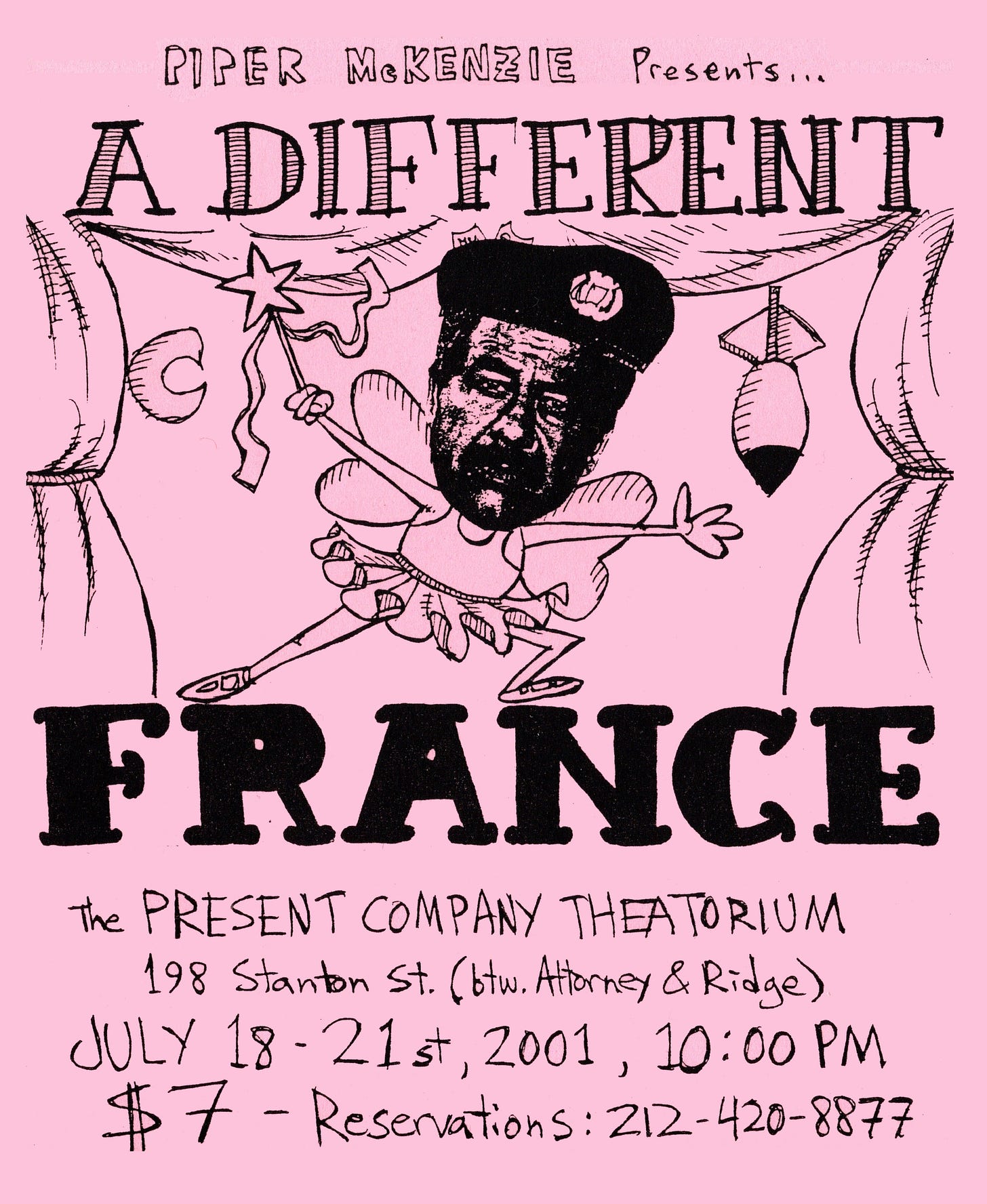

History of a Defunct Theater Company, Part 5: A Different France

Starring a teenage girl as Saddam Hussein

This is the latest part of an ongoing series that provides a show-by-show memoir of Piper McKenzie, the theater company I formed with my wife Hope in the late ‘90s.

A week or so before any theater production opens, it undergoes an ontological crisis. (“What is ‘show?’”) Producers should try to schedule this in, because it’s inevitable. Directors, actors and/or some of the less sturdy behind-the-scenes folks turn into feral lizards, staring jerkily around, bewildered and covered in sweat, as if waking up from a terrible nightmare. Something is horribly broken, and various solutions are put forward to fix it; in most of these cases, the cure is worse than the disease. Generally, the process works itself out and things return to normal in time for a live audience, but some shows never recover.

In the case of Piper McKenzie’s third show, A Different France, this crisis led us to scrap our show altogether and build a new one atop its ashes - all in the course of a single week.

The story begins right after our ambivalent experience in FringeNYC 2000. Frustrated with the limitations of writing and casting a “play,” we decided we might attract more committed performers if our next show went back to the collaborative roots of our first one. Around this time, I read a book about the working methods of British director Mike Leigh.I can’t say his work ever hit my sweet spot as a viewer (warty realism not really being my thing), but I was very intrigued to learn about how his plays and movies were devised through an actor-driven process. He started by working with individual performers to create complex, fine-grained characters, which he then slowly brought together for structured improvisations that eventually assumed the shape of a story.

Despite having no experience with this method, and very little temperamental affinity for it, we decided to make it the foundation of our next show. To accomplish this, we decided that, for the first time in our company’s (short) history, we wouldn’t co-direct - Hope would devote her entire attention to her role, while I would guide the process without appearing onstage.

I’ll be honest, there’s a lot about this process I don’t remember. What I do remember is that we started with three actresses and decided early on that they would all play teenagers. Being all around the same age, we set our improvisations during our own high school years - early 1991, on the eve of the first (and, this being 2000, the only) Gulf War. We spent a few weeks following the process, doing improv exercises individually and then in pairs, developing some characters and relationships that could be turned into a script.

And then, a pause. I have no memory of what stalled us - maybe we ran out of money for rehearsals, maybe there were scheduling conflicts, maybe we couldn’t manage to book a space. Whatever the cause, we decided to put the project on the back burner for a while.

During that hiatus, we made a fateful decision. A former classmate of ours had just moved to NYC and was eager to start creating their own work. In a burst of misguided altruism, we offered to produce their first show for them. We had visions of being creative producers like Joseph Papp, enlisting other artists to help us bring a larger vision to life. We looked forward to having input on a project from a different position and exploring a new approach to collaboration.

That’s not, of course, how it worked. Our friend was very strong-willed and had their own ideas about how to do things. The result was a lot of time and money spent supporting a vision that didn’t have any room for us other than as patrons and administrators. We once again found ourselves in the role of the sour, rotten adults spoiling everyone’s fun. For better or worse, we would rarely stick our necks out like that again.

Hungry for ways to bounce back from a profoundly unsatisfying, friendship-straining experience, we grasped at the idea of returning to the high school show. In the intervening months, one of the actresses had become unavailable, but rather than start from scratch we decided to continue the project as a two-hander between Hope and the remaining performer.

Befitting the workshop nature of the project, we booked a weekend at one of the scraggliest and most forlorn of all the Lower East Side theater spaces: the Downtown Variety Lounge. This flimsy coffin of a room was carved out of the lobby of the Present Company Theatorium, a much larger stage run by the same producers behind FringeNYC. What it had going for it was that it was cheap - no money up front, and a split box office after the first $50 or so. The tech was something like three lights and a boom box, and you could maybe seat 20 people. At least we wouldn’t have to worry about big, empty houses!

Based on all of the inputs from the first leg of the process, we settled on a storyline about two misfit teens: Rory was an aspiring actress who was far more concerned with the upcoming auditions for a community production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Lesley was an awkward wallflower incapable of recognizing or understanding her romantic attraction to Rory. Assigned to create a project for English class about the looming Operation Desert Storm, they improvised a radio play that mocked their teacher, wallowed in the unpleasant emotions of teenhood, and ultimately exposed fissures within their relationship.

This was all fine and good, but it somehow wasn’t us. The Leigh process, haphazardly executed, led us in the direction of an earnest realism that ran counter to everything we were interested in. I wrote a script based on our structured improvs, but rehearsing it felt strained and forced. We had the sinking feeling that we were going down the wrong path, and that we were going to be facing a reprise of our disappointing debut two years earlier.

About a week before we were set to open, the three of us gathered at Veselka1 to talk about how we could save the show. It turns out that NO ONE was happy with the direction things had taken. Hope and I were feeling very fatalistic about it - the train was in motion, and it was too late to do anything about it, right?

This is when we learned about the magic of working with the right collaborators. Because our third party asked the question we weren’t capable of asking ourselves: Can’t we just do this differently? Now that we knew what we didn’t want, could we use our remaining time to reimagine what the show could be? Like, what if we were to take what we had and completely retool it as a ridiculous, over-the-top comedy?

It was as if the clouds parted: Yes, the show could be saved - but only if we were willing to make a bold leap of faith.

It was a scary prospect, but also exciting. Because I’d been in this position once before.

During my junior year of high school, my submission to the Connecticut Young Playwrights Competition was one of six plays chosen to be staged. It was an overwhelmingly exciting moment for me, but there was a hitch: Despite its selection, the script was deemed to be inappropriate, and I was asked to make significant rewrites.

The thing is, they weren’t wrong. I had written an outrageously inappropriate absurdist piece called “Three Savages in Ugly Boxers,” in which the titular trio’s gibberish-spewing slapstick antics disrupt the quiet life of a struggling writer. In retrospect, it’s astonishing that a responsible adult organization would select something like this for potential production. I guess they saw potential but knew they’d have to make changes after they got me in the door. The problem was, we only had a week to do it. My assigned director had some suggestions, but, being petulant and indignant and 16 years old, I hated all of them. Instead, I spent the following days frantically scribbling a completely rewriting the play on a yellow legal pad during all of my classes.

The result was a new piece called “The Demon Children,” which replaced the savages with cartoonishly destructive brats and transformed the original edgelord story into a straight-up farce that built to a fever pitch of merry chaos. My frustration had somehow been spun into gold: It was undeniably a better play, and the high of writing under that kind of pressure is was a thrill that I didn’t experience again until the week we reimagined A Different France.2

About the only funny thing about the original script was its knowingly ridiculous title: A Different France. We kept that, along with the broad outlines of Rory and Lesley’s characters. They still needed to complete an English assignment about Operation Desert Storm, but everything else was distorted, cracked into pieces, chewed up and spat back out.

I joined the cast as the girls’ sleazy English teacher, Mr. Biederbecke, who meets the girls at the local mall to force them to complete their project. We piled on dozens of bizarre details: Lesley’s manager at the local McDonald’s is a bee. Mr. Biederbecke mounts a poetry reading in the food court for an audience of zero. Rory discovers a catalogue of every object on sale at the mall, and her orders are delivered by a fourth, silent character that a friend was generous enough to jump in and play at the last minute. Rory and Lesley transform into increasingly bizarre versions of George H. W. Bush and Saddam Hussein (a femme fatale, a Frenchman, a cheerleader, a hippie). The whole thing climaxes with the characters coming up with the idea for the era’s sub-”We Are the World” celebrity propaganda piece, “Voices That Care.”

By the time we opened, we had no idea what to expect. We were exhausted and exhilarated by the process of pulling a new show out of our asses, and in a sense it didn’t matter what anyone thought. And yet, our audiences loved it! This was still almost entirely our circle of friends and acquaintances, but the sentiment was 100 times warmer and more appreciative than after our previous outings. We hadn’t only surprised ourselves, we had surprised everyone else!

The key, I think, was that we didn’t have time to think about good or bad - it was just pure behavior. I don’t normally like working under pressure, but that’s probably because it’s not enough. When the pressure is so intense that there’s no time to think, that’s when you figure out what really matters.

I won’t hesitate to say that the secret weapon in this piece was trusting our collaborator. Not only did she pull me and Hope out of our rut, her creative contributions gave the show a flavor we could never have achieved on her own. She wrote much of her own material and really championed going further and weirder at every step. In contrast to our previous disappointing experience as hands-off producers, this collaboration was a truly simpatico synthesis of sense and sensibility. It’s no accident that we continued to work on various projects for years afterward and remain good friends today.

Looking back on Piper McKenzie’s history, I’ve often wondered why we didn’t do more bratty, angry, mean, and silly shows like A Different France. I think a big part of the answer was the timing. Part of the show’s absurdity was its look back, 10 years later, at what had come to be regarded as a non-event - the first Persian Gulf War. the joke was on us. Just a few weeks after our run, two planes flew into the World Trade Center, barely more than a mile away from the Downtown Variety Lounge.

Rather than a new beginning, the play turned out to be a farewell to a certain vision of the 1990s, the one that was concerned with irony and selling out and the vaunted “end of history.” Not for the first time and not for the last, the bottom fell out underneath us - and this time, from beneath the entire world. When we were to come back the following year, it would be from a completely different direction, one that looked deeper into the ugliness of the past - and, though we didn’t know it at the time, into the ugly future as well.

My freshman year in college, well before we were a couple, Hope came up to me and said, “You write plays, right? I’m sick of this theater department; let’s put one up in our dorm lounge.” So a restaged version of “The Demon Children” was technically our first collaboration, and the direct predecessor of Piper McKenzie.