History of a Defunct Theater Company, Part 3: The Walking in Space Show

Two small children with no idea what they're doing

This is the third part of an ongoing series that provides a show-by-show memoir of Piper McKenzie, the theater company I formed with my wife Hope in the late ‘90s. The first two parts were shared in my old newsletter format, but I’ve migrated them over to Substack and removed the paywall so everyone can get up to speed on one of the most important stories of our time:

When Hope and I arrived in NYC on March 1, 1999, we were in no position to start producing plays. We had no savings, no connections, and no jobs beyond putting our names on file at a temp agency. But making theater was what we came to do, so it was time to get started.

In our eyes, we were escaping the confines of a stuffy theater education, where all attempts at experimental expression had been thwarted before they had a chance to grow. The head of the department for about 40 years had been a British expat whose friendly nickname, Bill, belied a forbidding academic sensibility. We mounted three mainstage productions a semester, and the written word was paramount. Directors, actors, and designers had to do their best to support the vision of the playwright, who was generally also British and forbidding and quite likely dead. Spareness was the order of the day. Bard College at the time was stuffed to bursting with gleeful liberal arts experimentation, but Bill’s domain was like a dour fiefdom amidst the scrum. We cursed him with one breath while flaunting our willful alienation from the rest of the school with the next.

In contrast to the mainstage, during classroom hours individual professors had free rein to cultivate their idiosyncracies. Most colorful by far was an Iranian expatriate theater artist we knew as Bani. He had been an outspoken and flamboyant art star in his native country but was forced to flee during the Revolution, eventually washing up at Bard. Bani’s every gesture presented an invigorating contrast to Bill’s stodgy regime. His was the anything-goes theater class, where we didn’t work on scripts or scenes but instead mounted wild improvisations that shot you across the cosmos over two hungover Friday-morning hours. Sitting in on one of Bani’s classes during a college visit was the entire reason I applied to Bard.

Learning from Bani was like staring into the sun - dazzling and dangerous. He wasn’t disciplined enough to lead a cult, but he still held many of us under a spell. Unfortunately, halfway through our matriculation he was fired following a very bizarre sexual-harassment scandal, when he wouldn’t stop pressing a female student for information about her boyfriend’s genitals. It took me years of learning and growing to acknowledge that maybe he shouldn’t have done that.

By the time we arrived in the City, Bani was living in squalor on the Lower East Side - his one day a week of teaching had been his main source of income, and he burned every possible bridge on his way out. But he was still a god to us, so we were eager to connect with him. When we gave him a call, he shared an important fact: Applications to the New York International Fringe Festival were due in less than a week.

This was galling to hear, because participating in the Fringe was a key part of our artistic plan – in fact, it was the only part of our plan. The previous summer, we had driven down from upstate to see Bani perform in a Fringe show he’d written, but we misread the schedule and showed up on the wrong day. So we watched another show instead, and it absolutely blew our minds. It was an experimental riff on a Columbo episode created by rising downtown mainstays Radiohole, filled with snarky dialogue, a bleepy/squonky soundtrack, and a guy dancing in a diaper. It turned out the company was founded by earlier Bard graduates, but this was nothing like the old-school theater department we had shared. Apparently we could do ANYTHING down here!

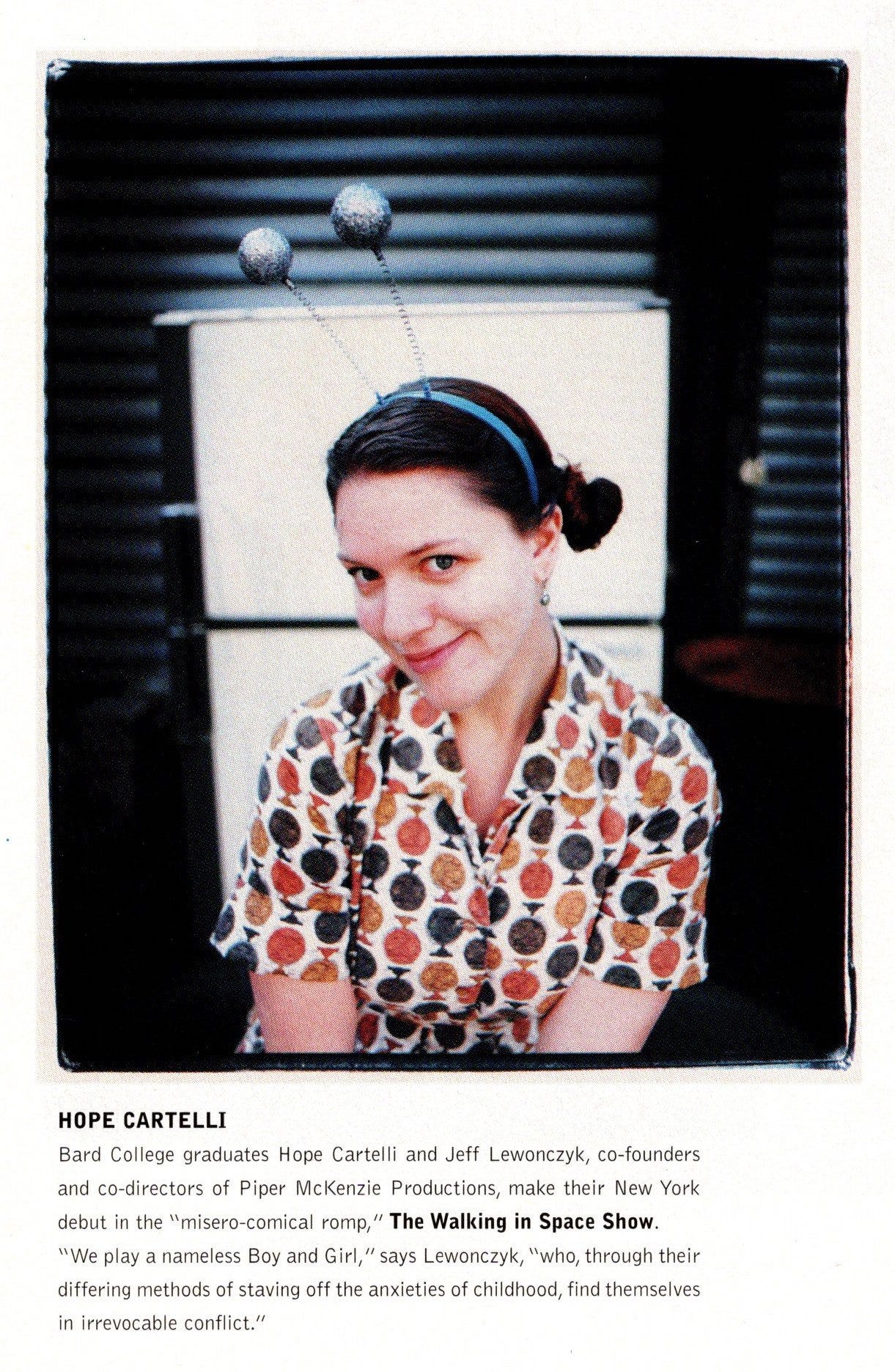

Right after speaking to Bani, Hope and I repaired to a Bowery dive bar named Phoebe’s (still there!) to down some five-dollar pitchers (not still there!) and hash out the show we were going to submit. We had been discussing a number of possibilities, but they were all too ambitious. There was no time to drum up other collaborators, so everything would be up to the two of us - the writing, the directing, the acting, the production, all of it. Sifting through a list of half-cooked concepts, we pulled together an outline about two kids who get lost in their own imaginary world. We were interested in exploring the terrifying absurdity of childhood, quixotically thinking that portraying children would be easy - it was so far in the past, we thought! I spent the weekend furiously writing a script, and we made the deadline by less than an hour.

We were cocky enough to assume we’d be accepted, but it still felt good to be right. Only in its third year, the Fringe was still a Wild West upstart, and I suspect it was easier to get in than be rejected. (Urinetown, the show whose Broadway transfer turned the festival into a behemoth, premiered this same year as us.) It also helped that our production was incredibly minimal – just two actors on a bare stage, no props or set or anything. This is one of the reasons we decided to name it The Walking in Space Show – it was literally just the two of us, walking in a space, depicting kids who pretended they were also walking in space. Adding to the excitement, our application for a one-night stand at HERE Art Center’s American Living Room Festival was also accepted. We were making it in New York – and it was all so easy!

Of course, there was still the small matter of mounting the show. With absolutely no money or resources, our initial rehearsal space was our kitchen. But having a roommate who might not appreciate a lot of thumping and hollering right outside his bedroom door, we also needed a Plan B. This turned out to be a small, tree-lined clearing just north of the Sheep Meadow in Central Park. Located 100 feet or so from any paths, it was generally empty enough to avoid interruption. It also had the advantage of being the midpoint between our latest temp gigs – me in a trailer on the construction site for the Museum of Natural History’s new Hayden Planetarium, and Hope at the New York Academy of Sciences in Midtown East.

Alas, there was nothing remotely scientific about our creative process, unless it was to establish the ideal conditions for generating a class A shitstorm. The pressures of finding our way in the city would have been tough enough without the added burden of pulling together a show mere weeks after moving. Without any collaborators to absorb the noise, our anxieties bounced back and forth across the empty room of our partnership, getting louder with every echo. I remember one day we got into a meltdown argument in the park, when this guy on a bike pulled up to watch us fight. Hope finally yelled at him, “You have a whole park, leave us the fuck alone!” The guy said, “Whatever, you’re the crazy ones,” and rode off. He wasn’t wrong.

By the time the Fringe rolled around in August, we’d met a few people. Bani had remounted his show that spring – a remarkable monologue about secret Nazis called Something Something Uber Alles, which I wish in retrospect had been a lot less prophetic. When we met up for drinks afterward, Hope recognized a guy that she had gone to performing-arts camp with, who had come to see Bani’s show with an actor who was starring in his one-man production of Dostoyevsky’s Notes From Underground around the corner. We also met Bani’s director, another earlier Bard alum who would go on to become a prominent theater critic and hire me to write reviews. We didn’t know it yet, but these people became the nucleus of our longtime artistic community in New York.

But before we could reach the future, we had to make our debut. Unfortunately, the show itself was entrenching an unhealthy dynamic between me and Hope. The story revolved around the cleverly-named Boy (me), an anxiety-ridden milksop of a lad who balked at the prospect of anything that challenged his constrained worldview. Girl (Hope) was his next-door neighbor, intrepid and outspoken, who dragged him into all sorts of imaginary games that quickly spiraled out of control. This wasn’t a direct reflection of our relationship, but boy, was Boy rubbing off on me. Or the other way around. The character was supposed to be petulant and strained, but everything I brought to it was also petulant and strained, which created a maudlin feedback loop. Nothing was working out the way I’d hoped - the only bright point of the whole project were a series of several manic dance numbers, accompanied by a mashup of Hanna-Barbera stingers, which were intended to embody the kids’ TV-addled gestalt. Jumping around to these nostalgic riffs was the only time I felt anything akin to the pleasure that acting had always brought me in the past.

Opening night loomed, but the black clouds lifted a bit when we got our hands on a Fringe catalogue and saw our names in print. This was really happening! Maybe we weren’t sure about what we were doing, but the audience would vindicate us. We were young and likable, and people couldn’t help but appreciate our efforts. After all, this was US on the stage - walking in space, with nothing else to hide behind. We may have been battered and bruised, but we were ready at long last to take the New York theater world by storm.

And finally, it was the big night. We peered through the curtains at our inaugural audience – both of them. This was not the glorious entrance we had anticipated. It was not the last time I would have to drag myself through an entire performance trapped in a bubble of disappointment, but at the time it felt like the absolute end of the world.

Our audiences stayed stuck in the single digits for the next four performances. I had imagined people pouring in from the street, attracted by - what, exactly? Our vague, 40-word show description in the catalogue? The ineffable aura emanating from our persons across the tenements of the Lower East Side? Instead, my gut seized up every time we walked into the theater, begging fate to throw us a bone.

My spirits lifted before our American Living Room performance, which landed near the end of our Fringe run. We were sharing the bill with a performance by a trapeze artist, and as we stood backstage we heard the laughter and applause of a sizable audience – this was more like it. But as soon as we walked out to perform, we were horrified to see people get up and walk out – followed a scene later by more, and then by still more after that. Halfway through our show, half the audience had disappeared. Perhaps some had only been there for the opener, but the rest simply didn’t want to watch what we were doing. We ran out of the theater that night burning with shame.

We had one Fringe performance left, our last shot at redemption on a Sunday afternoon. Our families were coming, Bani was coming, all of our new friends were coming – it would be our first full house (of 20 people, but still). We sauntered into the theater ready to accept our due, only to discover with horror that we had left our audiotapes on the table at home.

These tapes were essential to the show. It had become clear by this point in the run that my script was flat and forced, as were our characterizations. Maybe we were too close to still being kids to have anything cogent to say about it; maybe the strain of our process had prevented the show from growing into itself. Either way, these ridiculous cartoon dance sequences, which were weird and energetic and embodied what we were getting at in a way the dialogue only hinted at, were the only part of the show that actually worked. It would have been deadly without them.

There was still 30 minutes until the show, and since our running time was shorter than scheduled, we rushed back to Brooklyn in a cab to grab the tapes. We made it with something like two minutes to spare. After leaping out of the taxi to the applause of our waiting audience, adrenaline carried us through the next hour.

But even then, it wasn’t exactly a triumph. Most people were blandly pleasant, congratulating us without being too specific. Before we left the theater, Bani came up to share his opinion. “It was very difficult to watch,” he told me. “I didn’t understand what you were doing, and I didn’t trust your character at all. The only part I liked was your dancing. That should have been the entire show.” He saw many of our shows in the years that followed, and rarely had a kind word for any of them.

In an unexpected epilogue, the American Living Room asked us to come back for their encore series in September. It’s kind of a mystery why this happened, but it was likely in part because the production was so hassle-free to host. In any event, we were excited to have another shot.

For one of our two dates, the audience consisted of my sister and a college friend who came down from school to visit. The final performance had just one attendee – Bill, the elderly head of our former theater department. He had just retired to his Manhattan apartment after a decades-long career, and he made the trek downtown to come see us. It shouldn’t have been surprising - we had rolling our eyes at his dusty sensibilities for so long that it was easy to forget he had spent countless hours trying to serve as a mentor, an effort we barely appreciated at the time.

We emerged from the dressing room cross-eyed with chagrin – this wasn’t how we wanted him to see us. As we stood in the empty lobby, he told us warmly that he was proud of us for getting our start, even though the show wasn’t very good.

“The problem”, he told us, “is that you didn’t give yourself anything to work against. You acted as if these characters were fully formed from the start, which left you with nowhere to go. It’s very hard to create a world of just two people - you need something else, something from the outside. You need to let the world in first.”

It was the last thing he said to us - a few months later, he was dead.

And with that, The Walking in Space Show closed forever. We were now officially New York Theater Artists.

The trapeze artist was Carla Cantrelle.

My god, what memories this story brings back. I was in that American Living Room festival also, with "The Universe of Despair," my first full-fledged play in NYC. I remember seeing your show! (I was not one of the walk-outs.) But I would not meet you until a few years later in 2003, when you reviewed me in the NYC fringe.