History of a Defunct Theater Company, Part 4: The Infinity Six Versus Half a Dozen of The Other

A life on the Fringe

This is the latest part of an ongoing series that provides a show-by-show memoir of Piper McKenzie, the theater company I formed with my wife Hope in the late ‘90s.

Theater, to paraphrase Jean-Paul Sartre, is other people.

For sheer scope of humanity, no experience in my 15 years of producing low-budget spectacles came close to the New York International Fringe Festival. Founded in 1997, FringeNYC spent two weeks every August attempting to reproduce the scale and diversity of New York City through 200 shows of every size and description spread out over a couple of dozen downtown venues. It had its last go in 2019, after hosting many thousands of theater artists from the five boroughs and around the world. Across its two decades of existence, it was a messy, insane, mind-melting hotbed of creative ferment and low-budget dysfunction. There was nothing else like it - and probably never will be again.

For all of its flaws and insanity, the Fringe was a remarkably populist institution - in fact, that’s largely where the flaws and insanity came from. At least in the early days, you didn’t need an impressive resume to get accepted - just an interesting hook, a solid application, and a talent for believing your own bullshit. That’s why Hope and I, under the auspices of Piper McKenzie, produced our first New York show at the Fringe, and why, despite a soul-searchingly miserable experience, we decided to give it another go the following year.

The origins of this second outing can be traced to a weekly gathering of the new friends and colleagues we accrued during our first year in the city. The group was centered around people under the thrall of our former college professor, the exiled Iranian artist Bani Babilla - most were not Bard graduates, but had met Bani either through other former alumni or experiences in the still somewhat tight-knit downtown scene that the Fringe spiraled out from. Though Bani himself rarely appeared, this small conclave of burgeoning theatrical auteurs - christened the Legion of Doom by one or another of its participating wags - gathered every Monday night in a rented rehearsal room to discuss new projects, share work in progress, and generally flaunt our youthful arrogance.

The building where we met was another downtown institution whose time has passed: the Charas/El Bohio community center on East 9th Street. By the turn of the millennium - barely a decade out from the Tompkins Square Riots - the tenor of the East Village had begun to decisively tip toward gentrification, and Charas was a concrete manifestation of the changes that have turned the area into an unaffordable simulacrum of countercultures past. A hulking former public school, Charas had been converted into a thriving neighborhood institution in 1979. Primarily a social and cultural hub for the local Latino population, it also played host to middle-class transplants like us, who were indirectly responsible for driving up rents and welcoming big money into this previously low-income neighborhood. As it turned out, the building was in a legal limbo for the entire time we worked there, eventually being bought up for development by a Giuliani crony in 2001. Tragically, it has spent the past 22 years sitting empty and rotting - time it could have been making a major difference for thousands of people. Fucking New York, man.

As the Legion of Doom started meeting during the months following The Walking in Space Show, I licked my wounds by writing a series of snarky, intellectual comedy sketches. Under the steady influence of Jorge Luis Borges, David Foster Wallace, the looming smallness of living in the big city, and whatever weed I could get my hands on, I found my imagination circling around the concept of infinity. These absurdist scenelets generally depicted ordinary people baffled by the vast unknowability of the cosmos. They were simultaneously juvenile and pretentious, just like me and my friends. After reading these scenes out loud at a handful of Legion meetings, Hope and I decided to tie them together as our next show.

The framing concept, such as it was, was that the sketches would be performed by six actors depicting a group of people/entities/life forms/superheroes/angels/ demons/whatever dubbed the Infinity Six, who were tasked with the responsibility of acting out every conceivable scenario that the human mind could come up with. What we were showing onstage was just an infinitesimal sliver of what could possibly be, a heartbeat in time that demonstrated a range of the absurdities and paradoxes demanded by the infinite. Feeling small, I guess I had the inclination to think big.

By this time, some of our college friends had begun to wash up in NYC, and we managed to rope a few of them into joining Hope and I as the cast. Though I loved each of these people as individuals, it ended up being a very motley gang of folks with exceedingly different personal styles, levels of interest in the project, and degrees of comfort with our group’s whole doing-a-show-on-a-shoestring-for-no-money ethos. In retrospect, the only thing we really had in common was that we were almost entirely white, straight, well-educated, and momentarily delusional about the likelihood of building a theater career in New York.

Since the Fringe at that point would accept nearly anything, our show was accepted again. (They didn’t even mind our unwieldy full title: The Infinity Six Versus Half a Dozen of The Other. There were reasons we called it that, but they don’t make sense anymore.) Based on our previous Fringe experience, we decided to keep the physical production as pared-down as possible: The only set or props we had were six foldable stools that were arranged in different configurations depending on the scene. This was partly out of budgetary and logistics concerns, but partly to keep the focus on My Brilliant Writing. We mimed the props, improv-style, but put most of the budget in the audience’s imagination. Several times a week, we met to rehearse in a crumbling former classroom building at Charas - the only place whose rates (I believe $10/hour) we could afford on our office-temp wages.

Alas, whatever challenges Hope and I had with each other the previous year were multiplied sixfold with the addition of new collaborators. None of us burgeoning grown-ups had the greatest handle on the rigors and responsibilities of creating independent collaborative art. One performer called us asking to cancel rehearsal because it was raining. Another threw a chair across the room during an argument over exactly nothing. The show’s two co-directors (i.e., me and Hope) bickered constantly in front of the cast, while the writer (i.e., me) fought hammer, tooth, and nail against the removal of a single one of his Precious Words. We may have viewed ourselves as functioning adults, but each one of us was still at least 85% child.

In one incident that perfectly captures the low-stakes clusterfuck of the Fringe experience, our group’s collective immaturity clashed directly with the festival’s often draconian factory-style production model. With so many shows crammed into each venue, there were nauseatingly fast changeover times between shows, and no one - NO ONE - was allowed to leave props, costumes, or set pieces in the theater. Even our six stupid little dollar-store folding stools proved to be a hassle, and the cast deeply resented our decision to make them responsible for carrying one back and forth from each performance. One day, we showed up for our call time only to get blazingly chewed out by the venue director. Apparently one of the actors had preferred to secret his three-pound, flat-folded piece of plastic and metal in a hidden spot backstage, where it had been promptly discovered. We might as well have desecrated a historic church for the amount of blowback we got from this - recrimination that we of course passed along to the offender, who hurled fury back at us for expecting him to carry this minimal weight in the first place. The intensity of the drama stood in direct proportion to how little any of it actually mattered.

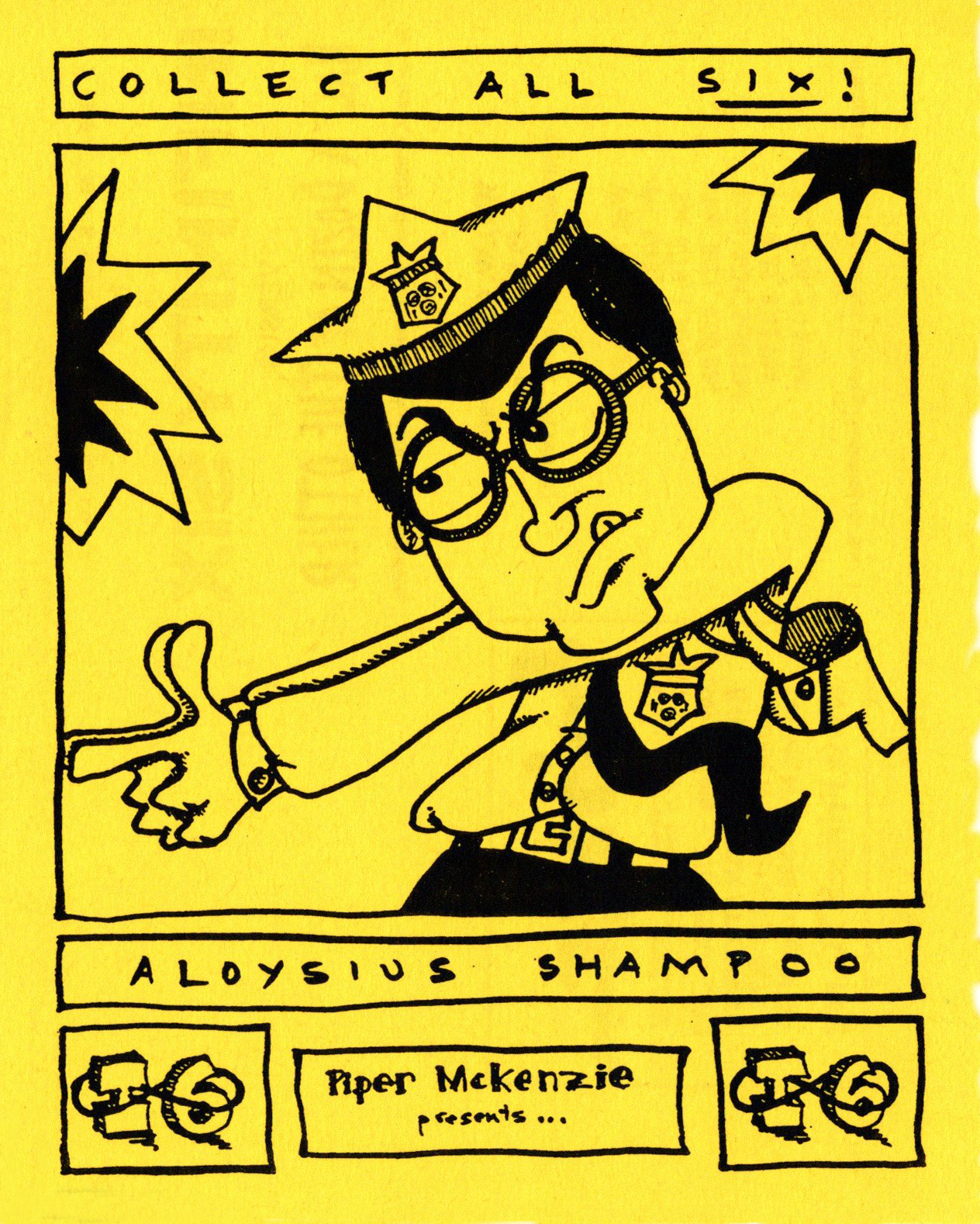

Another Fringe lesson we failed to master was the importance of marketing. Once again, we thought our charm and passion - bolstered by a new handful of friends - would cascade unceasing positive word of mouth through the entire festival, and once again, we were wrong. I was galled, because this time, instead of one hand-drawn postcard, I created six, depicting each performer as one of the show’s many characters. How fun and irresistible! Unfortunately, nobody knew who these characters were, and nobody really cared. We didn’t have a sexy title, a pop-culture connection, evocative photography, or even a helpful description to encourage audiences to come see the show, so, for the most part, they didn’t.

Even among those who did come, the feedback was not great. At one post-show dinner with several Legion of Doomers, an awkward silence reigned. Hope eventually burst out, “Do you have ANYTHING to say about the show?” One person murmured about how it was such a NEW show, they didn’t want to compromise it by providing premature feedback. Another suggested, “Have you considered using props?” A different member, after another performance, said, “Yeah, I don’t know, I’m suspicious of things that are clever.” These people may have been right, but that didn’t help at the time.

Still, despite all the dings, it’s hard to overemphasize what a scene the Fringe was in those days. We probably wouldn’t have come back if not for the electric vibe that coursed through the streets during the two weeks the festival was live. In those days, the venues were all within walking distance of each other in the East Village and Lower East Side, and you’d constantly collide with groups of frantic theatergoers rushing from one theater to the next. People would sit down and map out elaborate itineraries to try and schedule out as many shows as possible - often Fringing for 12 hours straight. Creators and crew automatically received (free? half-price?) tickets, space available, so you and your fellow artists would be running amok as well, squeezing every drop from your experience. If the stars aligned, dozens of complete strangers would roll up to your show when you least expected it.

And so that’s how we ended up having one glorious late-night performance in front of a raucous, appreciative crowd who went nuts for our dumbest jokes and grooved along with the tinpot philosophy. It was an unlikely and never-to-be-reproduced room full of like-minded hipster-stoners, temporary participants in a downtown scene that still enabled serendipity. For 90 short minutes, I understood exactly what we were doing and why we were doing it. It was the kind of wild, one-of-a-kind moment that became increasingly rarer as the very sociopolitical elements that brought a thriving theater scene to downtown Manhattan pushed it back out again, without so much as a thank-you along the way.

A few days later, the Fringe was over. Hope and I were eating in an East Village Mexican restaurant (anyone remember Mary Ann’s?) when some rando walked over to our table and said, “Hey, were you two in that show last week? The Infinity something? You guys were awesome! It was one of my favorite things I’ve ever seen at the Fringe. You know, the intellectual-geek factor…”

“The intellectual-geek factor!” It proved to me once and for all: My audience was out there, somewhere. I just had to find it.

23 years later, I’m still looking.

I love alllll of this.