History of a Defunct Theater Company, Part 6: The Water Hen

Nothing more lonely than the avant garde

This is the latest part of an ongoing series that provides a show-by-show memoir of Piper McKenzie, the theater company I formed with my wife Hope in the late ‘90s.

I don’t read plays very often anymore. After two decades of extrapolating the written word into the theater of my mind, I burnt out on it. Most playscripts aren’t intended to be engaging reads on their own; they’re written for a communal context rather than solitary pursuit. So as soon as the effort was decoupled from my theatrical ambitions, it started to feel like a slog. Where are the actors? Where’s the audience?

But there’s one pleasure in particular I miss from my days of regular script-reading: the hot, dizzy sensation I’d get whenever the words on the page fell into such harmony with the images in my head that they’d prompt the most dangerous four words in the director’s phrasebook: “I can do this.”

That tingle hit me hardest at some point in early 2001, during a read-aloud session at a friend’s living room in Hell’s Kitchen. The loose alliance of off-off-off-off-off-Broadway theater artists formerly known as the Legion of Doom had drifted apart and reformed as a weekly apartment meetup with the equally silly name of the Ladies’ Auxiliary. Now, instead of workshopping our own material, we exploited our office jobs to photocopy already existing but woefully neglected plays, read them out loud together, and discuss. On this particular occasion, the host chose a play called The Water Hen, the best-known work by an obscure Polish playwright named Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz. I played the lead role, and every word that came out of my mouth increased my desire to direct and star in this play.

I recently revisited The Water Hen for the first time in 20 years, and I couldn’t quite recapture what I originally saw in it. Sure, this was partly due to reading silently in my head instead of aloud with a roomful of friends. But it’s also because I know how things turned out. It felt like yelling at the screen during a horror movie: “Don’t make that creative choice!” Bringing it to the stage wasn’t the first or last time my ambition outstripped my abilities, but it proved to be a formative entry in a pattern that would last for years: narcissistic excitement about an outsized concept crashing hard into pitifully limited means.

To help you better understand what we were getting into, here’s a little background on the life and work of Witkiewicz. Born in 1885, he grew up in the resort town of Zakopane, Poland, as the son of a successful regional painter, designer, and theorist. Taking the nom de plume of Witkacy (vit-KOT-zee), he inherited his father’s polymathic ambition - and then some - but infused it with a dark modernist twist. Restless, rebellious, and grandiose, Witkacy brought a flamboyant fatalism to every medium he touched: painting, photography, novels, aesthetic theory, theater. One of his most notorious gambits was the S.I. Witkiewicz Portrait Painting Company, in which he produced commissions on a sliding scale based on whichever drug he ingested beforehand. (The Public Domain Review has a great rundown of that project, where I also grabbed some of the images below.) Less prankish was his Theory of Pure Form, positing an approach to art in which narrative and representational elements play a subservient role to formal elements like color, shape, structure, and rhythm. The Water Hen was written with these principles at the forefront.

Not that I knew any of this during that first reading. Instead, playing the role of Edgar Valpor - a clear stand-in for the author - felt like surfing a wave of wild absurdity. It wasn’t the mannered nonsense of an Ionesco or the antic bleakness of a Beckett, but something more feral and unpredictable - not to mention written in 1921, a good three decades before the Theater of the Absurd. The play opens with Edgar aiming a rifle at his paramour, a mysterious woman known as the Water Hen, who flirtatiously urges him to execute her. When she dies, a son appears; when she resurfaces later in the play, the son falls in love with her. Meanwhile, Edgar marries an ice-cold noblewoman and fends off the criminal upstart who craves her affections, while a trio of old men plot a utopian future. Arbitrary events spawn capricious actions: characters are whisked to new settings in the course of a single line, their motivations transformed with a shift in the lighting. It’s impossible to see in one moment what will happen in the next. The play ends with a bloody revolution that isn’t even hinted at in the previous scenes.

But what hit me just as hard as the unhinged narrative was the humor. Witkacy’s words and images are all funhouse jabs at the emerging modern canon - think Chekhov’s The Seagull, Ibsen’s The Wild Duck. The tone veers from drawing-room parody to wild slapstick to profane mysticism. My impulse, especially in my 20s, was always to lean hard into comedy, so my reading squeezed every possible drop of campiness and burlesque out of the script. Hope, reading the role of the Water Hen, felt a similar affinity to the piece, and we decided that we had to make it our next Piper McKenzie production.

As it happened, it took more than a year to make our dream come true. We ended up staging a different show first, and then 9/11 happened and we were at all sorts of loose ends for a few months. But, in an attempt to learn from our previous mistakes, we spent our time slowly and carefully laying the groundwork. Learning that the play’s English translator, Daniel Gerould, was a professor at CUNY’s Graduate Center, we paid him a visit and got his blessing in advance. For the first time, we lined up a full team of designers and offstage collaborators - including the friend who introduced us to the play, who came on as dramaturg - and we held auditions to bring new actors into the fold. After four years of producing shows, it finally felt like we were doing it right.

But when it comes to Witkacy, false confidence is dangerously misplaced. The play is subtitled “A Spherical Tragedy,” and, despite all our preparations, as soon as we started rehearsals I felt myself slipping off its surface. This was due to many of the usual problems: not enough money, not enough experience, not enough time. As circumstances had it, the small investment firm I worked for during the day decided to make a post-9/11 migration out of the City. I planned to stay on long enough to collect my year-end bonus, but I soon discovered it was how hard it was to search for jobs while working out of state. And so I spent most of our rehearsal process taking a punishing daily commute from Park Slope to Greenwich, CT - over two hours in each direction. I rolled into our rented studio each night famished and fatigued.

Exacerbating all of this was my decision to direct myself as Edgar. Despite all the dents and dings our previous productions had made in my confidence, I still thought that I was capable of doing it all. Instead, my hubris amplified all the other issues and opened up a screaming inner void of panic that I never quite overcame.

The truth is, I related deeply to Edgar, who Witkacy portrays as a solipsistic nebbish molded like putty by the characters around him. I might have been able to turn in a decent performance if I hadn’t also been trying to wrangle the rest of the production. Likewise, I might have found creative ways to overcome some of our production constraints if I had focused on the big picture rather than myself. As it was, my approach to this complex and mystifying play was to bring it down to the level of campy farce that we enjoyed during the first reading - Witkacy for Dummies, essentially. Watering down his vision of Pure Form may have been the most viable way of getting the thing done, but it left out much of what made the play so haunting.

Most of the cast and designers were as green as I was, and they worked valiantly to make something out of the spotty support I was able to give them (assuaged, as always, by Hope’s organizational acumen and calmer bedside manner as a co-producer). But some people could clearly smell my fear. The dramaturg who first introduced us to the play turned out to be a prickly collaborator who strongly disagreed with my (admittedly unsophisticated) vision for the project. She ended up getting so fed up with my halting approach and shallow understanding of the material that one Saturday afternoon she started going over my head and directing the actors herself. I was so abashed by the situation that multiple people had to pull me aside and ask what the hell was going on - it was practically a scene from the play itself. After nearly surrendering the final scraps of my authority as director, I had to confront her and insist we part ways. The whole experience galvanized the cast for a day or two, but it wasn’t long before my creative terror began to seep back into the process - what the hell were we trying to do?

During our initial meeting a few months earlier, Daniel Gerould had excitedly told us that a performance of a different Witkacy play would be opening right before ours - it was the first time multiple Witkacy shows would be performed simultaneously in New York. And so, the week before our opening, Hope and I went to La Mama excited to see our hero’s work staged for the first time and share our love of his work with the creators.

The production we attended was a world premiere - the first performance in English of one of Witkacy’s more obscure plays (as if they weren’t all obscure). It was apparent from the opening moments that this group had more of everything: more money, more ambition, more self-assurance. Live musicians played an original score, there elaborate papier-mache puppet heads, and the cast performed every beat with disciplined sharpness. Instead of trying to make the play more accessible, like we were attempting with The Water Hen, this production leaned into the stranger, spikier elements of Witkacy’s vision. It wasn’t always clear what was happening and why, but they had clearly taken Pure Form very seriously. As we watched, our inspiration curdled into despair - how could we possibly compete with this?

Still, we were excited to connect with other admirers of Witkacy, so we stayed behind after the show to introduce ourselves to the director. We imagined it would buoy our spirits to talk shop and invite these like-minded artists to come enjoy our own humble effort to bring this deserving weirdo back to the New York stage.

Instead, it was one of the most humiliating conversations of my life. When the director finally appeared, it was clear she’d rather have been cleaning the La Mama toilets than wasting her time with us. She listened to our enthusiastic praise with proudly unconcealed disdain, regarding the Water Hen postcard we handed her as if it was a used snot rag proffered by filthy street urchins. After making it implicitly clear that she would be neither accepting our offer of free tickets nor extending it to her cast and crew, she bid us good day and disappeared backstage as quickly as the bare minimum of etiquette allowed.

We were crushed. Our perceived betrayal from one of the few people we felt we could count on to support our project haunted us up to opening night and beyond. Looking back, I’ve tried to give her grace - she was exhausted from a difficult job, and god knows we could come off like yappy little pups. But to have been pushed away not despite but because of a shared fringe interest made us feel more isolated than ever.

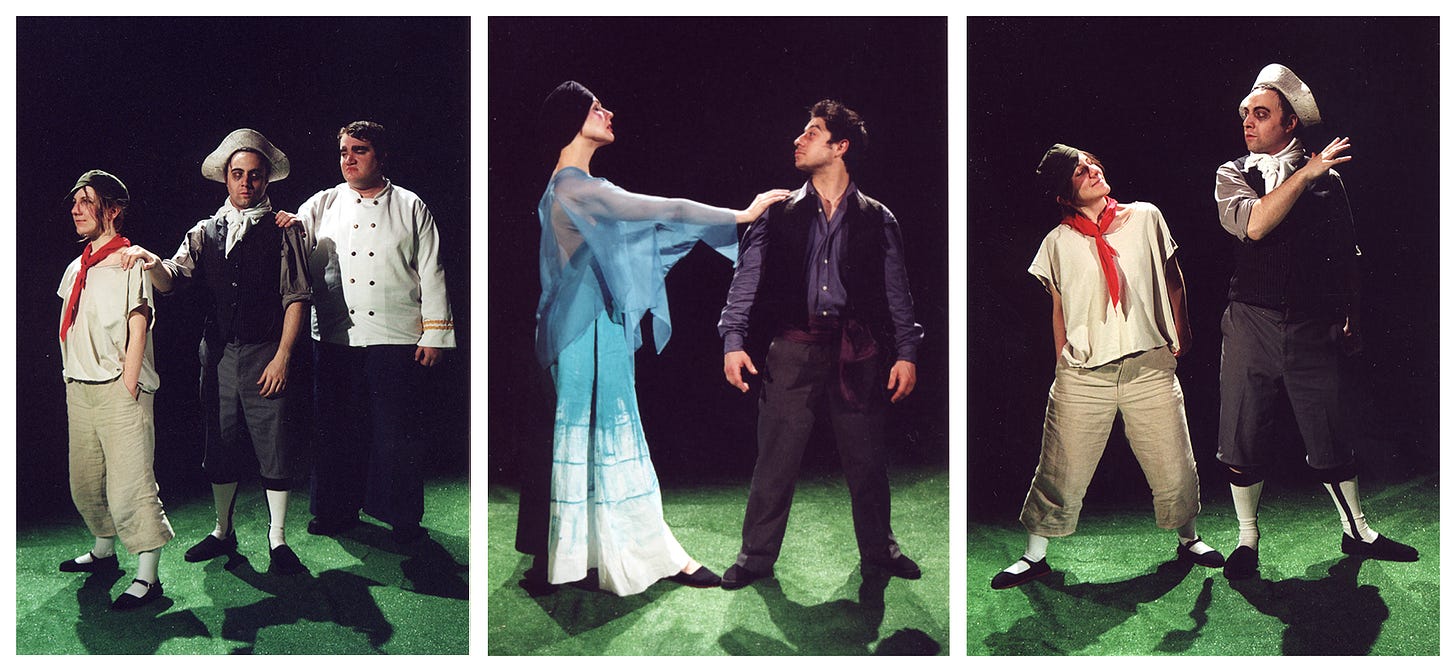

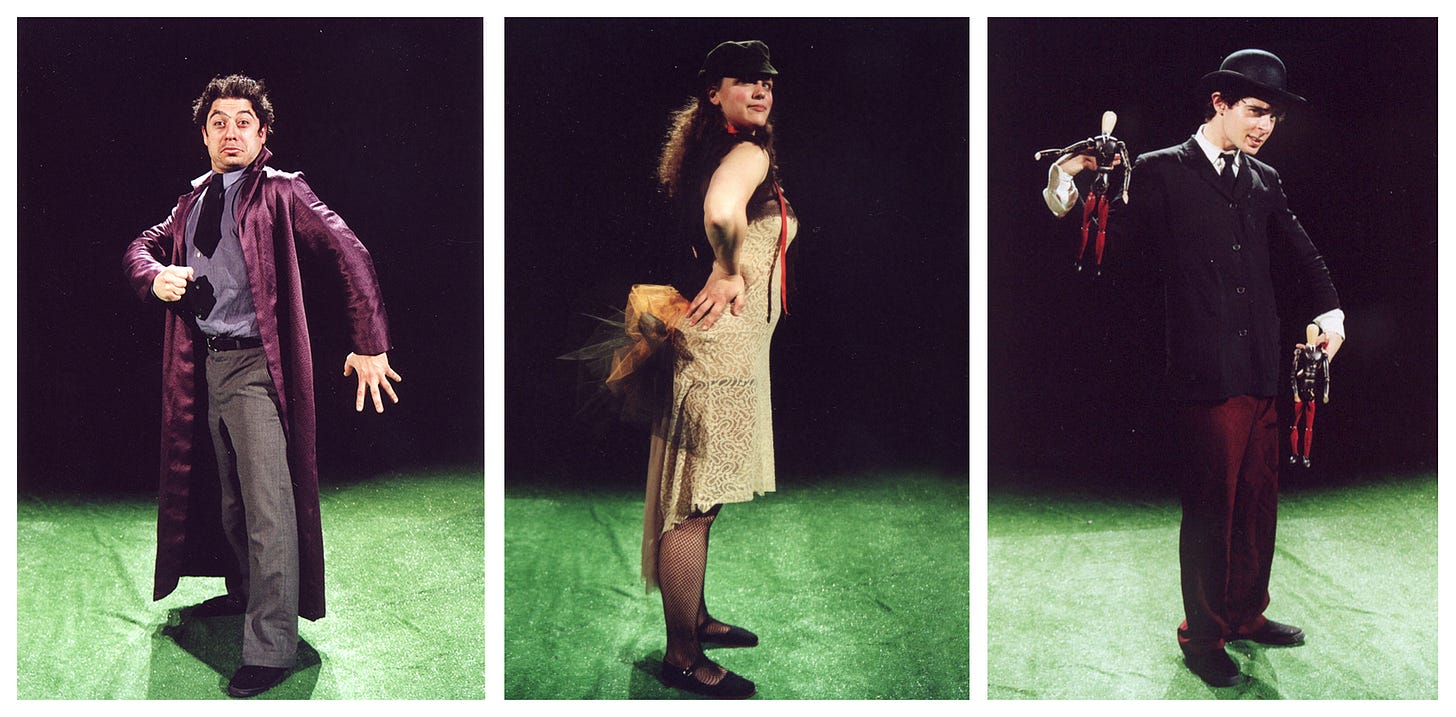

And suddenly, it was opening night, April 2002. I ended up leaving my job right before tech week, so I was hopeful I’d get the rest and focus I needed for the final stretch - but it was too little, too late. We were a jumble of miscellaneous artists barely pointing in the right direction, game for the attempt but in over our heads. Ticket sales for our two-week run were sluggish, and only one of our eight performances really connected with our audience - the final one, of course. We clearly didn’t know what we were doing, and neither did the people in the seats.

Witkacy’s own story had a far grimmer ending. Just as our production barely skimmed the surface of his work, I’ve barely hinted at the relentless anguish that flavored his biography and his intensely prolific output. He likely suffered from mental illness throughout his life, and his uncompromising and ironic approach to making art was not conducive to stable relationships or a lucrative career. In September 1939, when he was 54, the Nazis invaded Poland; two weeks later, the Red Army attacked from the other side. Witkiewicz had always had a foot in the future and a nose for impending totalitarianism, so he knew that this wouldn’t end well for him. He ended things himself by slitting his wrists under an oak tree. It would be three decades before his work was rediscovered in Poland, and its recognition by the rest of the world has been glacially slow.

If there’s a moral to this story, it’s that the avant garde is a very lonely place. Perhaps it’s a bit like Mount Everest: People climb it “because it’s there,” but most can’t finish the ascent - and the summit is littered with the corpses of those who do. I spent the process of The Water Hen resentful toward the job I needed in order to survive, resentful toward the extravagant expense of mounting even a bare-bones production, resentful of the people who treated me like I didn’t have a right to try. In a sense, they had me pegged - I was a lightweight. I didn’t have the brutal, single-minded will that Witkacy demonstrated his whole life: art above all else, and damn anyone who gets in the way. My problems with The Water Hen didn’t hold a candle to the brutal paradoxes of his life, but we did have one thing in common. Faced with doubt and derision at both ends - both from inside and without - I too folded. Fortunately, I was lucky enough to be facing laughably low stakes, where all I had to lose was my pride.

Our production of The Water Hen bore little resemblance to the galvanizing vision I experienced in that Hell’s Kitchen living room a year earlier. But we made some new friends and had a few interesting experiences along the way. The translator, Daniel Gerould, was very generous to us - as a kind, elderly man with a deep body of work, he had very little to prove, and he ensured we received a nice write-up in his publication, Slavic and East European Performance.

Most importantly, we would return to Witkacy two years later, with a far more successful production that built on the lessons we learned from The Water Hen - first and foremost being not to direct myself in a lead role. This turned out to be the last time I ever engaged in that particular folly - to which I say, good riddance. I may never be the artistic genius I once longed to be, but I’ve slowly learned to be more comfortable with what I’m not.