Two weeks ago, I announced the launch of slips slips, a new… well, I called it a literary journal, but I’m not sure if it’s as simple as that. My hope is that it will be an outlet for the unexpected, an experiment in words and pictures and design, a collection of modest printed anomalies. So let’s just say “publication.”

As with any publication, slips slips will have adoptive forebears that my co-editors Kristen and Hope and I will call upon for inspiration at various stages of its creation. Between now and November 24 - which I’ll seamlessly remind everyone is the deadline for submissions - I’m going to devote some Jeff Stream ink to a handful of these aspirational ancestors, starting today with the Push Pin Graphic.

The Push Pin Graphic is a bit of an umbrella term for a chain of related periodicals that were published from the 1950s through the 1980s as the house organ of the design firm Push Pin Studios. Founded exactly 70 years ago by four titans in the world of graphic design, Push Pin was essentially the Beatles of late 20th-century visual culture.

At its center are the Lennon-McCartney of illustration, the mercurially talented Milton Glaser and the affably prolific Seymour Chwast, who is amazingly still turning out steady work at age 93. Accompanying them were Edward Sorel, who left after three years to pursue his own career as a trenchant political and literary satirist (also still going strong at 95!) and the late Reynold Ruffins, one of the few prominent Black designers of the era, who is probably best known for his storied career in children’s picture books. Other legendary creatives passed through over the years, including the playfully elegant John Alcorn, faux-folk surrealist Paul Davis, and Lincoln Center’s iconic poster artist James McMullan.

Back in the sweltering summer of ‘54, Glaser, Chwast, and Sorel - all graduates of New York’s democratically exclusive Cooper Union - decided to ditch their day jobs and build on their modest freelance success by going into business on their own. (Fellow alum Ruffins joined the following year.) They chose the name Push Pin because they had already been using it. Starting in 1953, the nascent group had published the Push Pin Almanack as a showcase for their work. Printed at pamphlet size with an anthropomorphic woodcut pushpin on every cover, the Almanack bucked the minimal modernist design trends of the day by taking a playful look into the past. Like an avant-pop Poor Richard, each issue used found text like tongue-in-cheek folk maxims, vintage newspaper articles, and farm reports as the springboard for its own distinct brand of throwback graphic experiment - interspersed with free ads provided to the print specialists who helped bring the project to life.

By sending the Almanack to fellow designers and art directors, the collective gained enough attention to fuel the opening of their business. But by 1957, they began to feel that the clever quaintness of the Almanack had run its course, so after 15 issues they switched to a new name and format. The Push Pin Monthly Graphic was printed as an inexpensive but more expansive broadsheet to provide a larger and less creatively constrained canvas for the group’s increasingly ambitious explorations.

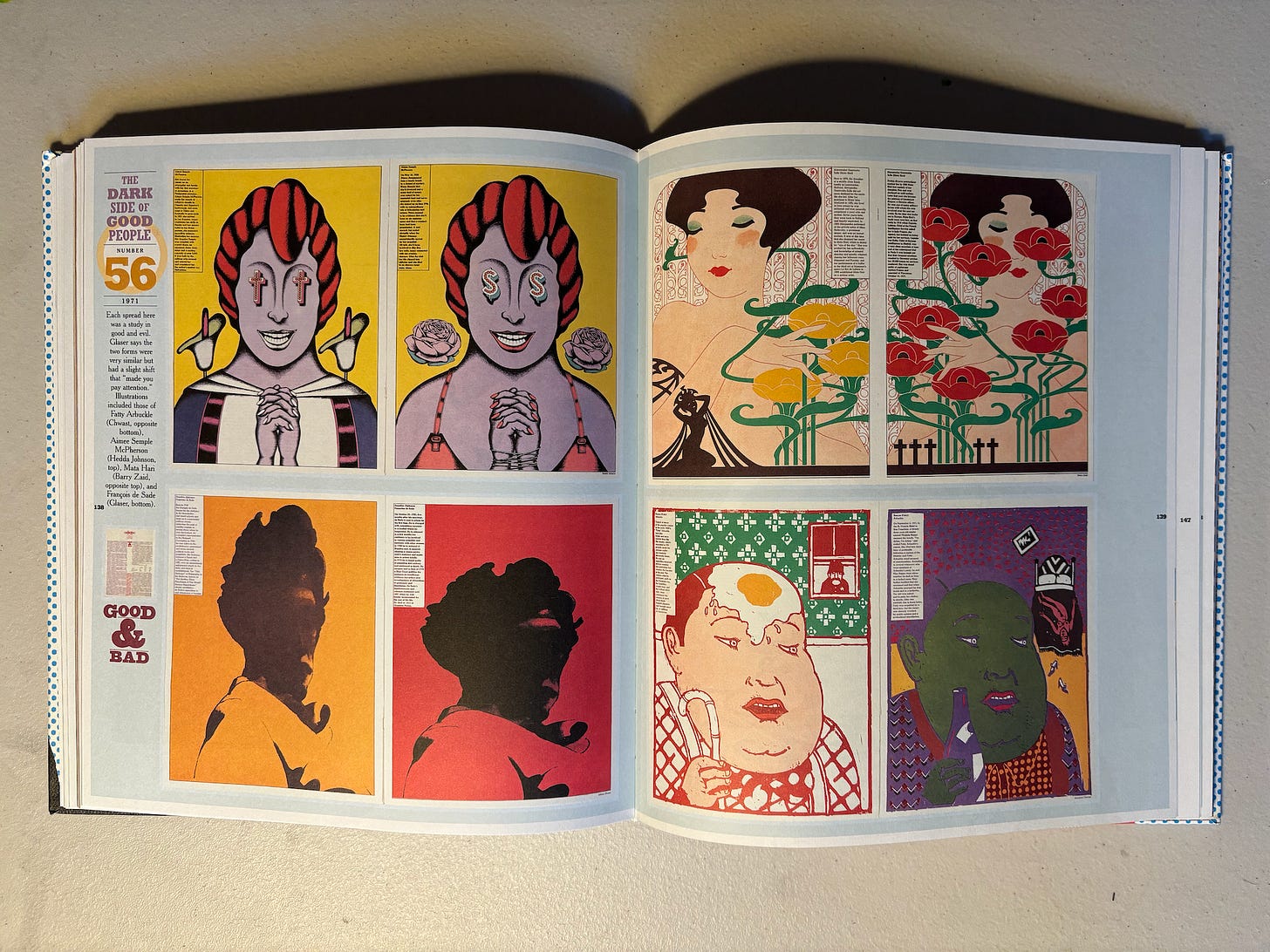

Each issue was structured around a theme that provided a loose connective tissue for the whims of the artists, ranging from the grand (Good Vs. Evil) to the goofy (Limericks). Along the way, each participant contributed to what in many ways became the house style of the 1960s - loose, funny, boundary-pushing, mind-expanding, and increasingly political, taking in the best of the past to build a vision of an eclectic, eccentric future. The Push Pin Graphic created the visual world that I grew up in - Glaser’s book covers, Chwast’s editorial illustrations, and Ruffins’s picture books all suffused my mind at a tender age, and flipping through images from the Graphic feels like looking at old photos of home.

Over time, Chwast, who mostly led the project, dropped the Monthly from its name because it was an unrealistic pace for the spec project of a busy design firm - but it kept coming out until 1980, for a total of 86 issues. Along the way, the publication adopted more of a traditional magazine format, with full color, fold-out posters, and other extravagances.

Chwast was the main constant, as Glaser left to form his own studio and a host of other artists came and went. He was also responsible for some of the publication’s most poignant contributions, including a 1967 issue devoted to “The South,” which provided a haunting juxtaposition of sentimental song lyrics and photos of civil rights martyrs, with a die-cut hole throughout the entire issue underscoring the violent history of the region.

So what connects the Push Pin Graphic to slips slips? When Push Pin Studios was founded in 1954, it was the project of four young firebrands on the make - beneath its flights of fancy was a solid wish to make their names and get paid. By contrast, slips slips is the project of three middle-aged creators who have already spent decades toiling on the literary and artistic fringe.

What we have in common is very little to lose - but even more so, a desire to explore the concept of a publication as a field of play. Sure, on the surface level, the old-timey content and approach of the Almanack and the early issues of the Graphic are a major influence on why we decided to experiment with a broadsheet format, and our inaugural theme of “Dispatches” provides a similarly informal focus for the content we’re soliciting. But more importantly, the Push Pin Graphic’s ability to constantly reinvent itself while refusing to take itself too seriously has been a serious stimulus to our collective imagination. We hope to bring some of that improvisational fury and magpie inclusiveness to slips slips. What’s it gonna be? I dunno, let’s do it and find out!

I’m deeply indebted the 2004 compilation The Push Pin Graphic, compiled by Chwast with an invaluable introduction by the design historian Stephen Heller (which is where most of the photos on this page came from). I have yet to get my hands on a physical copy of the Push Pin Graphic (and the Alamanack? Forget it), but I’ve taken inspiration from this book’s reproductions hundreds of times over the years.

If you’re an artist or a writer or anyone, really, who thinks it would be fun to be involved in something like this, check out the submission criteria for slips slips, and drop me a line if you have any ideas or questions.

Can I come over to your house and look at your push pin compilation volume?