Oh how lovely to live in NYC! I’ll never stop being grateful that I can wake up on a Saturday morning and make my way to an exhibition of work by one of my favorite artists, whose work embodies the very city I love.

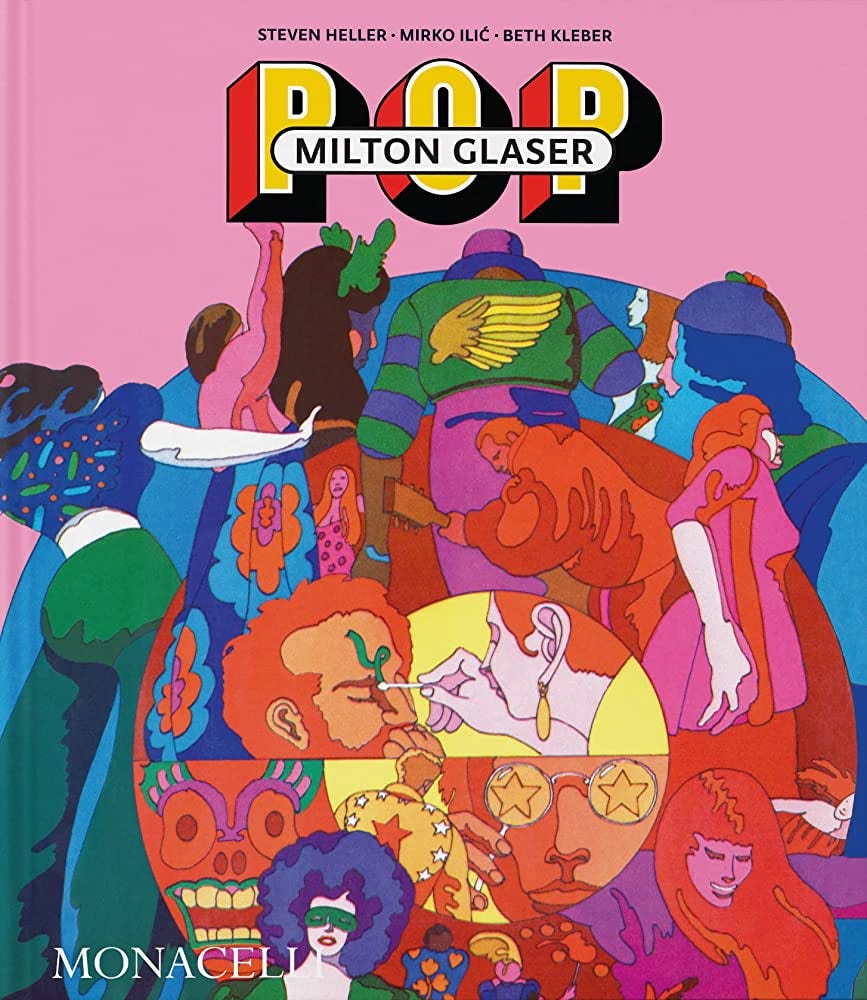

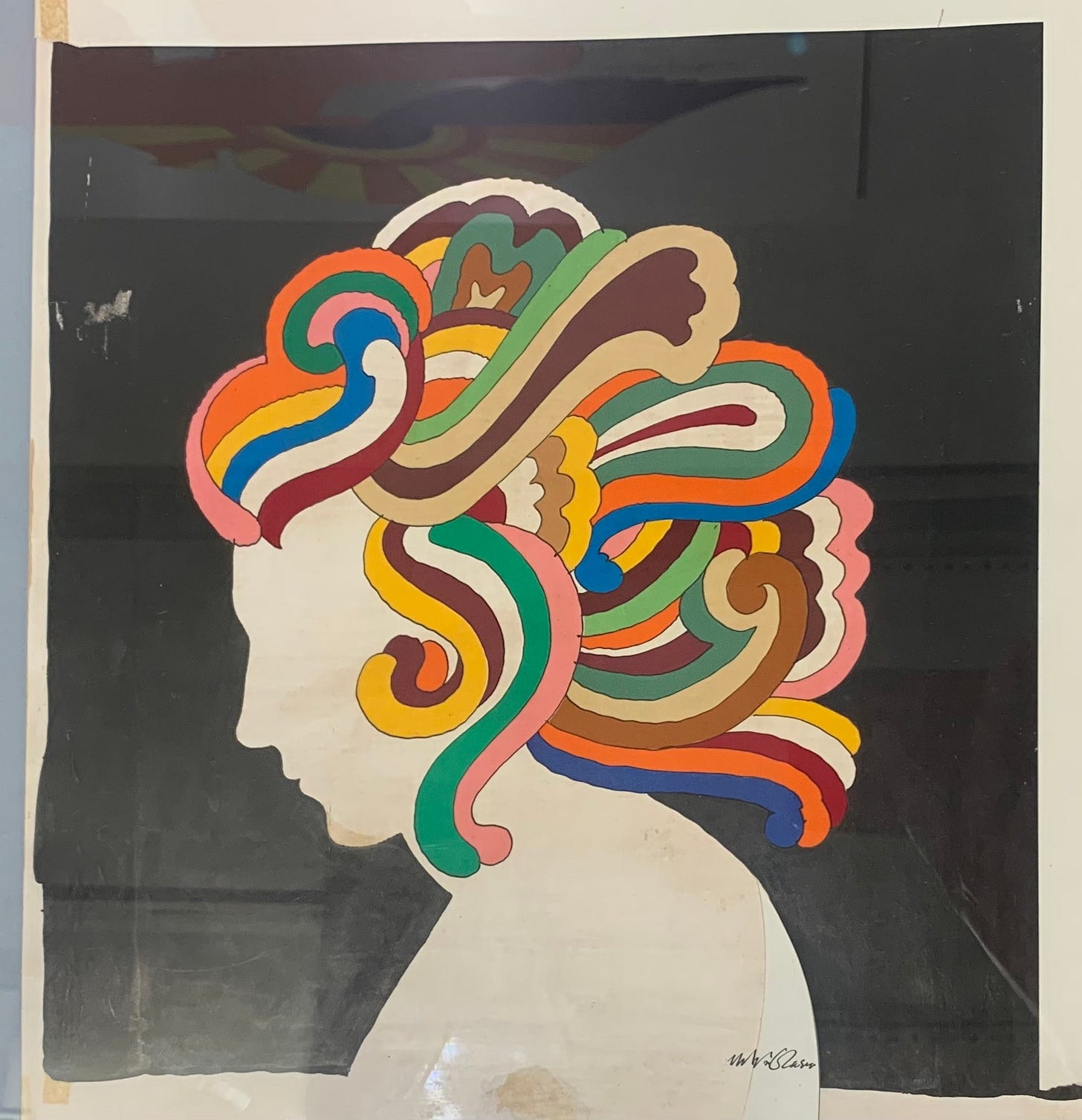

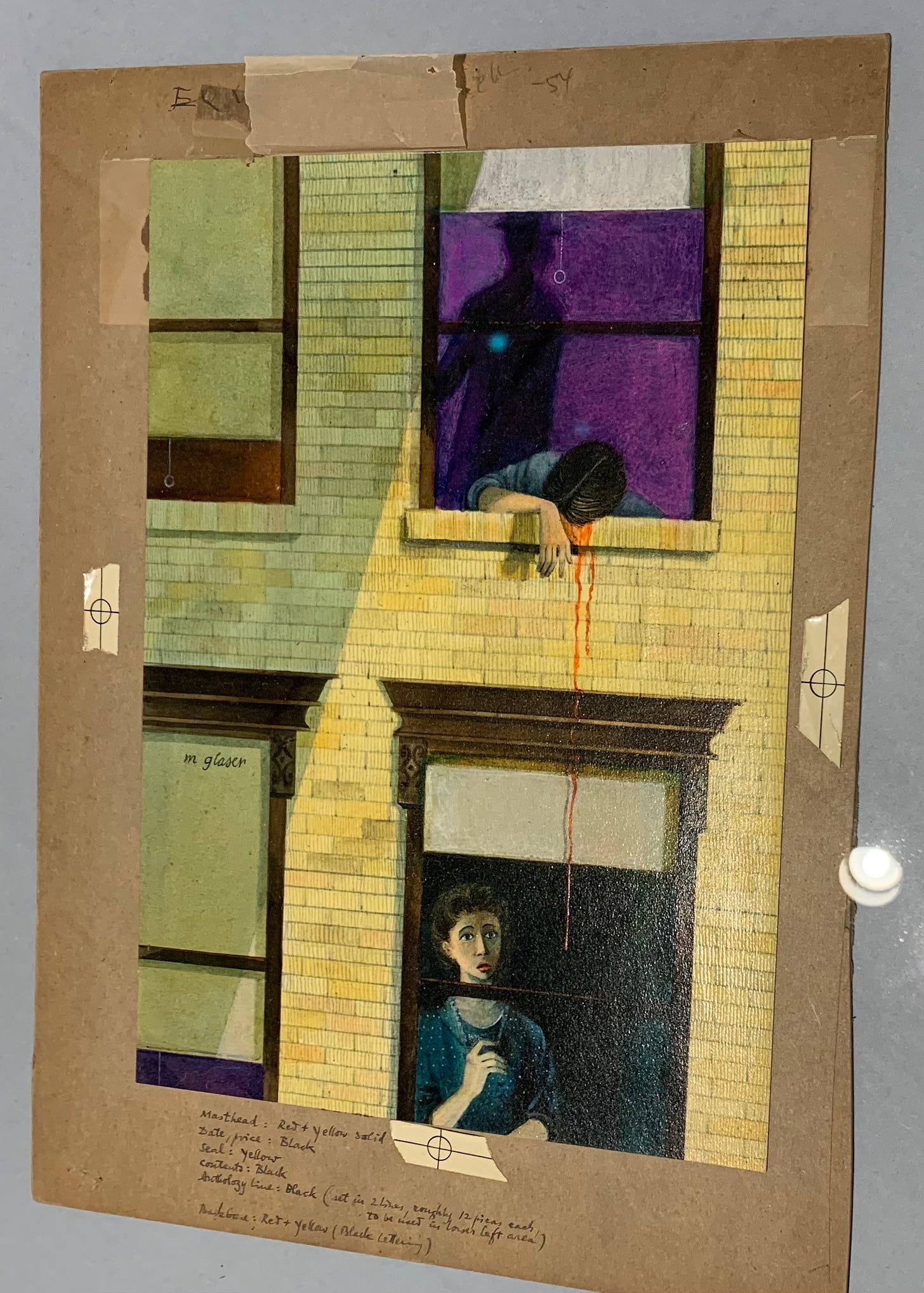

In this case, the artist in question is Milton Glaser (1929-2020), the legendary illustrator and designer whose work is on display until June 5 at the School of Visual Arts, where he taught for many years. The show is a companion to a wonderful new book - Milton Glaser: Pop - which covers his arguably most iconic period, from the ‘60s through the ‘70s. It features dozens of works both classic and obscure, many of which have been unearthed from SVA’s Glaser Archives for the first time in decades.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of Milton Glaser to my life - and probably to yours. As one of the most prolific and varied commercial artists of the 20th Century, you’ve seen his work everywhere - from his iconic Dylan poster to the I ♥️ NY logo, which feels so elemental that it’s hard to believe it didn’t always exist somewhere, just waiting to be discovered. Alongside his Push Pin Studios colleagues such Seymour Chwast, John Alcorn, Reynold Ruffins and others (not to mention fellow travelers like Heinz Edelmann and Peter Max), he created work that helped define one of the most heavily documented eras of recent history.

As a late Gen Xer - or very early millennial (though relating more to the former) - I grew up in a visual world that Glaser played a major role in creating. By the time I became aware of the pictorial artifacts that surrounded me - in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s - he had begun to move on from the psychedelic style that made him famous. But by then it had been fully absorbed into the culture, leaving its earmarks everywhere from TV ads to children’s books, Sesame Street to Time Magazine - all the stuff that a young American mind was exposed to at every turn. Directly or indirectly, his work shaped the way I see, think, and feel.

But my love of his output goes beyond simple nostalgia (though I’ll never underestimate the power of that particular drug). The sheer sense of play that he brought to his practice is inexhaustible and infectious. Seeing so much of his work all in one place like this, you have to walk away thinking he was one of the luckiest men who ever lived. He clearly had so much FUN treating every project like a new game - I’m sure that it was more of a grind than it looks from the outside, but as grinds go, it has to have been one of the better ones. He lived to a ripe old age, working the whole time, and he was tireless in support of causes he believed in. He was a beloved colleague, a generous mentor, and an all-around mensch. (Take a look at this excellent talk about the 10 lessons he learned, which I return to for affirmation every couple of years.) What more can you ask for?

The lens of this book and exhibit are interesting, because it feels like they’re trying to wrest the “pop” mantle from the better-known high-art movement of the same name. When most people think of “pop” in an artistic context, their minds go to Andy Warhol. Warhol was born less than a year before Glaser, and they both got their start as commercial artists around the same time - it’s fascinating to think of them as fellow jobbing craftsmen competing for the same gigs. But while Warhol brought the techniques and subject matter of commercialism into fine art, Glaser did the opposite, bringing his classical training and sense of modernist trends into new realms of the commercial sphere. I think that these are complementary phenomena, and that the fullest picture of that era’s visual culture requires paying attention to both of them.

But when all is said and done, If I had to choose between Warhol and Glaser, it would be Milton in a heartbeat. It could be an indication of how deeply I’ve internalized capitalism, but I’d much rather spend my life dwelling in Glaser’s experiments than Warhol’s. The variety, the curiosity, the sense of excitement that he brought to everything he did is infectious.

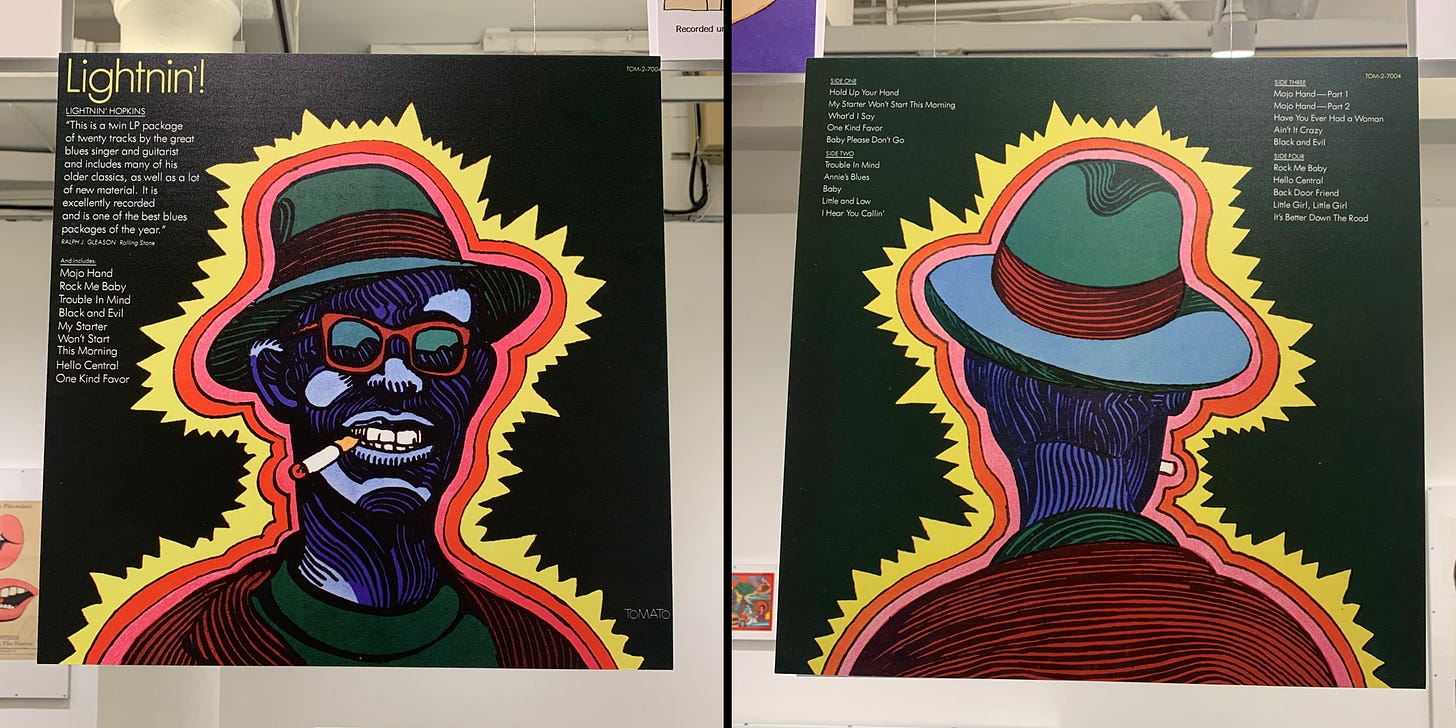

It helps that much of Glaser’s work was in service of the culture industry - his book and record covers are imaginative windows into the work of other artists, the opening salvo of conversations that continued through their works. I can’t tell you how many times reading Milton Glaser: Pop I found myself exclaiming, “I had that copy of that book! I had no idea that was Glaser!” My impressions of many different writers and musicians are viewed through a Glaserian lens - perhaps most significantly, Shakespeare, whose ink-scrawled Signet paperback covers defined his plays for me when I first started reading them as a teen, and in many cases still do. For all his high-art and celebrity-culture referencing, when I see a Warhol, I mostly just think of Warhol.

I’m constantly teasing out my relationship to fine versus commercial art. Those categories are less meaningful than they used to be, but it turns out the artists who speak to me most straddle the divide, with feet planted more firmly on the commercial side. Glaser is a perfect example, as are almost all other members of my personal canon, which includes the likes of Edward Gorey, Ronald Searle, and above all, Saul Steinberg, who transformed magazine cartooning into capital-A Art.

I wonder sometimes if what I’m attracted to is how these personal visions mix up our inner lives with the messy machinery of society. They point out how it was possible for people to make a buck while still making meaning. It seems much, much harder to do that nowadays than it was in the past - and that was even before AI developers targeted commercial art as the first object of its cynical technocratic takeover. So maybe this brings us back around to that nostalgia - a longing for a time when it was possible to make a living translating passion and play into widespread cultural relevance.

I fear that the phenomenal pairing of talent and timing that produced Glaser is unlikely to recur, at least not unless our culture gets a few more unexpected shocks. And it’s important to acknowledge that very few of his peers in the visual-culture racket of the time were women or people of color. But I still think his example provides an inexhaustible well of inspiration and enjoyment. I can think of few better ways to spend a Saturday afternoon than in the presence of his wonderful images.