After writing last week about a 23-year-old creative project I wrote and directed, I found myself stuck on some of the concepts that led me (just over 23 years old myself) to create it, and what has changed both in and around me since that time.

The Infinity Six was a play about the supposedly boundless possibilities of imagination, which we puny humans were unable to fully embrace due to fear, laziness, and stupidity. In the world of this show, imagination was an occasionally dubious but necessary good that was consistently devalued by a range of comical characters. The opening scene depicted a pair of newlyweds unexpectedly ushered to a subterranean cavern where the infinite possibilities of the cosmos laid open before them - but all things being equal, they decided to stick to their original plan and return to the Honeymoon Suite. There was a salesman who sold brains and couldn’t find a buyer. An inventor who “unvented” a perpetual motion machine. A pair of TV cops named Shampoo and Conditioner who were repeatedly thwarted by an omnipotent earth goddess. Stuff like that. I was fired up by creative possibility and wanted everyone else to feel the same.

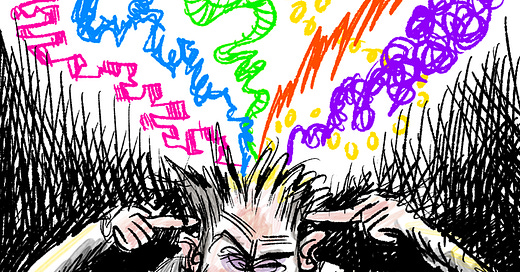

If I had been asked to define imagination at the time, I’d have probably said, “The ability to make things up” - or maybe “to see things that aren’t (yet) there.” The more bizarre, outré, unexpected, or unbelievable, the better. Imagination was a Dr. Seuss contraption of valves and pipes and filigreed flourishes that could serve functions beyond our conscious comprehension. Pure fancy, occasionally intersecting the waking world at right angles. Magic, essentially.

While this show had been my most direct expression of this thinking, all of our prior shows had contained elements of it, as had other writing I produced before and after. Over time, I encountered skepticism toward my half-baked “philosophy,” generally from people older and wiser than me. After revisiting these ideas for the first time in many years, I’ve begun to see their various points. Here are three anecdotes that help illuminate how.

1

In the middle of writing The Infinity Six, I had a very telling exchange with my ex-professor Assurbanipal “Bani” Babilla, an outsized genius/huckster/sad old man who I counted as my primary mentor at that time in life. We were at a Lower East Side party, smoking cigarettes on the fire escape, when he declared (apropos of god knows what): “The only infinite quality is love.”

“What about hate?” someone asked.

“Hate is the flip side of love; they’re the same force focused in different directions.”

I couldn’t let this stand. “I think our most infinite quality is imagination. The human mind is capable of creating things that can’t even exist, and it’s our only tool to understand the complexity of things that do. There’s no limit to what imagination can accomplish.”

“No,” Bani said with palpable disdain, as if I’d just asked if it would be a good idea to stick a fork in an electric socket. “Imagination has no qualities. It exists only as a vessel for love. Without love, imagination is nothing - it doesn’t exist.”

I indignantly disagreed, of course, and mounted the world’s most pretentious sketch comedy revue to prove it.

2

A few years earlier, when I was still a student, I had taken a poetry workshop with the poet Ann Lauterbach. Jumping off from my theatrical background, I wrote a poem called “Olga, Masha, Irina,” in which the speaker addressed Chekhov’s three sisters with a lengthy list of surreal fictional events that occurred after their time: “The vernal equinox was done in purple at Helsinki in 1929 / And the opportunity to follow whims has found itself increased by ten percent / Since 1952.”

The joke, which I didn’t really get at the time, was that the reality of the 20th Century would hardly have been less fantastical from their perspective, though the subversions and embellishments I created were a way to exercise my own developing voice.

Lauterbach liked the poem, but, discussing it in class, she made a remark that puzzled me - something to the effect of: “All that playing around with history - you can’t do that anymore past a certain age.”

It felt very reductive and sad to me, but I realize now she was making a similar point to Bani. Imagination illuminates experience, and the more experience you’ve had, the harder it is to make the world up. Living through history is less playful than projecting youthful optimism and irony onto it. Over time, life becomes far too real.

3

This one’s not so much an anecdote as another artist stating these lessons even more forcefully. A few years after my conversation with Bani, I stumbled on an essay by Federico Garcia Lorca, in which the great Spanish poet posits that imagination isn’t invention, but discovery.

The imagination is a spiritual apparatus, a luminous explorer of the world it discovers. The imagination fixes and gives clear life to fragments of the invisible reality where man is stirring…

The imagination is limited by reality: one cannot imagine what does not exist. It needs objects, landscapes, numbers, planets, and it requires the purest sort of logic to relate those things to one another. The imagination hovers over reason the way fragrance hovers over a flower, wafted on the breeze but tied, always, to the ineffable center of its origin.

Lorca goes on to argue that imagination is inferior to inspiration, which is the act of reality, in all its infinite nuance, impressing itself upon the poet. The poet no longer needs to make anything up - the world is enough.

I’m still not ready to go quite as far as Lorca. But over the years, I’ve come to accept that imagination is only as good as the diet it’s fed. This doesn’t only mean absorbing other works of art and culture (though that’s inevitable in a media-saturated world), but engaging fully in the world we travel through each day. The information we absorb through our senses is the raw material for the imagination - if we’re open to that.

True to what Bani told me on the fire escape, the promise of boundless imagination that I once envisioned now feels neutral at best. When I squint, it can even feel like a horrible burden - a gray goo of endless randomness failing to cohere. True to Lauterbach’s warning, my own capacity for imagining has been eroded by a gradual absorption of the world’s ugliness, which I was fortunate enough not to experience firsthand until I was an adult. I saw gleaming skyscrapers explode in flames, killing thousands. I’ve watched the reemergence of fascist themes and behaviors. I’ve lived through years of global pandemic. I’ve seen the sort of wars that I thought had been consigned to the barbaric past reemerge in full force. Literary games feel pretty small against such a backdrop.

When I contemplate the cruel, bloodless potential of imagination, I can’t help but think of the adherents of effective altruism, as personified by their fallen patron, Sam Bankman-Fried. A philosophy that relies upon envisioning and acting upon potential futures centuries or millennia hence sounds appealing on the surface, but in reality it’s so abstract as to be incoherent. Sure, you can imagine a world in which your smallest action today ramifies exponentially over time, giving you the power of a god over future generations. But what good does it do? Lacking the information to make such speculations meaningful, that kind of imagination threatens to produce havoc rather than heaven.

Thinking along these lines, Lorca’s more modest definition feels like a relief. We don’t need to take on the hubristic burden of inventing from whole cloth. Instead, creation can occur wherever we meet the world. As I’ve tried to reorient my artistic practice to reflect the humbler realities of my middle-aged life, I’ve begun to discover that imagination is most powerful when it arises inside the friction between idea and reality. The alchemy that I once though was entirely the product of my solitary mind actually exists in the space between conception and execution - between what I expect to happen and what actually occurs. The tooth of the paper as it pushes my pencil in one direction instead of another. The words I have to type to approximate the ideas in my head. The magnetic push or pull of a trusted collaborator. The unexpected observation that lights up the world around it. The seeds planted decades ago that finally begin to take root.

Since reality is just the transduction of concept and percept, imagination is both discovery and invention.