"Complicated Forms of Doubt and Pleasure"

The Lure of Imaginary Books

There are untold millions of books in the world, written in a staggering array of styles and voices, covering every subject imaginable. In my home alone I’ve gathered thousands of these volumes, tailored to every nuance of my taste, most of which I have yet to read. Thanks to the internet and the public library system, almost any title on record can be procured and held in my sweaty little hands within the week.

With so much bounty at my disposal, what accounts for my helpless fascination with all the books that don’t exist?

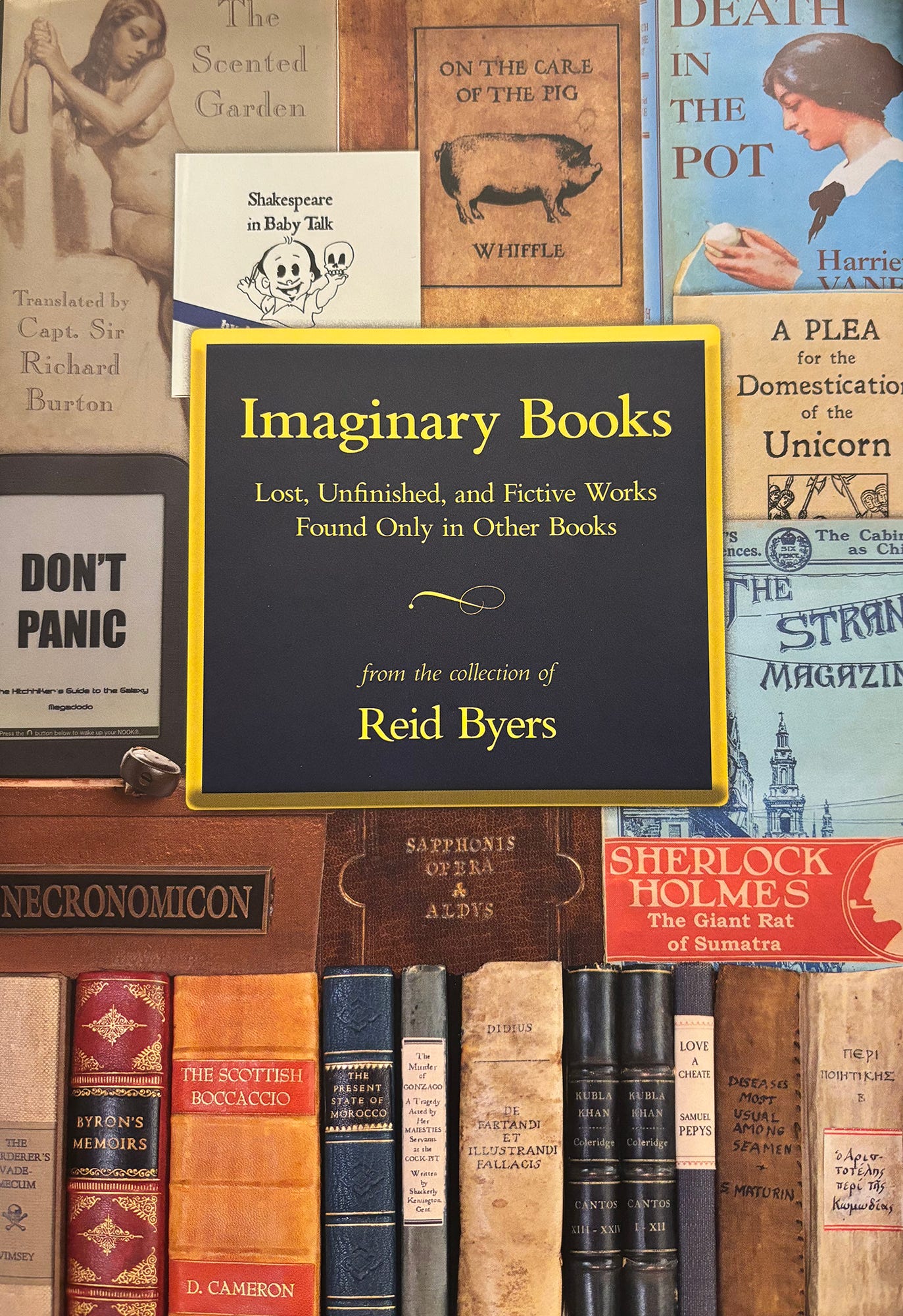

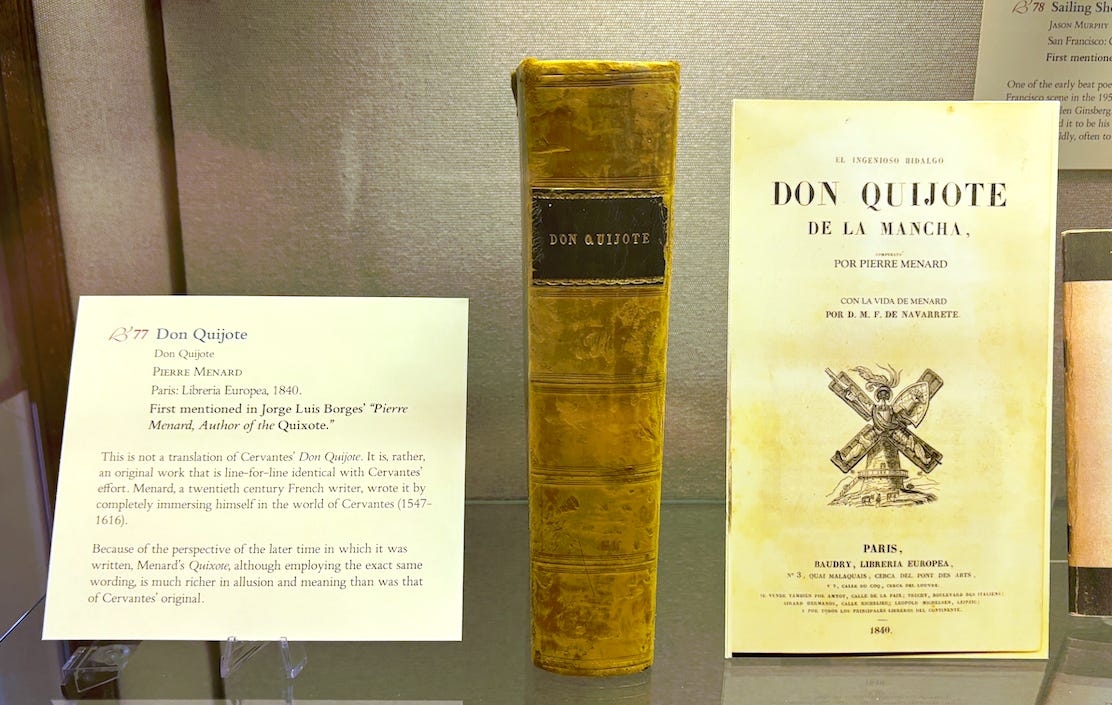

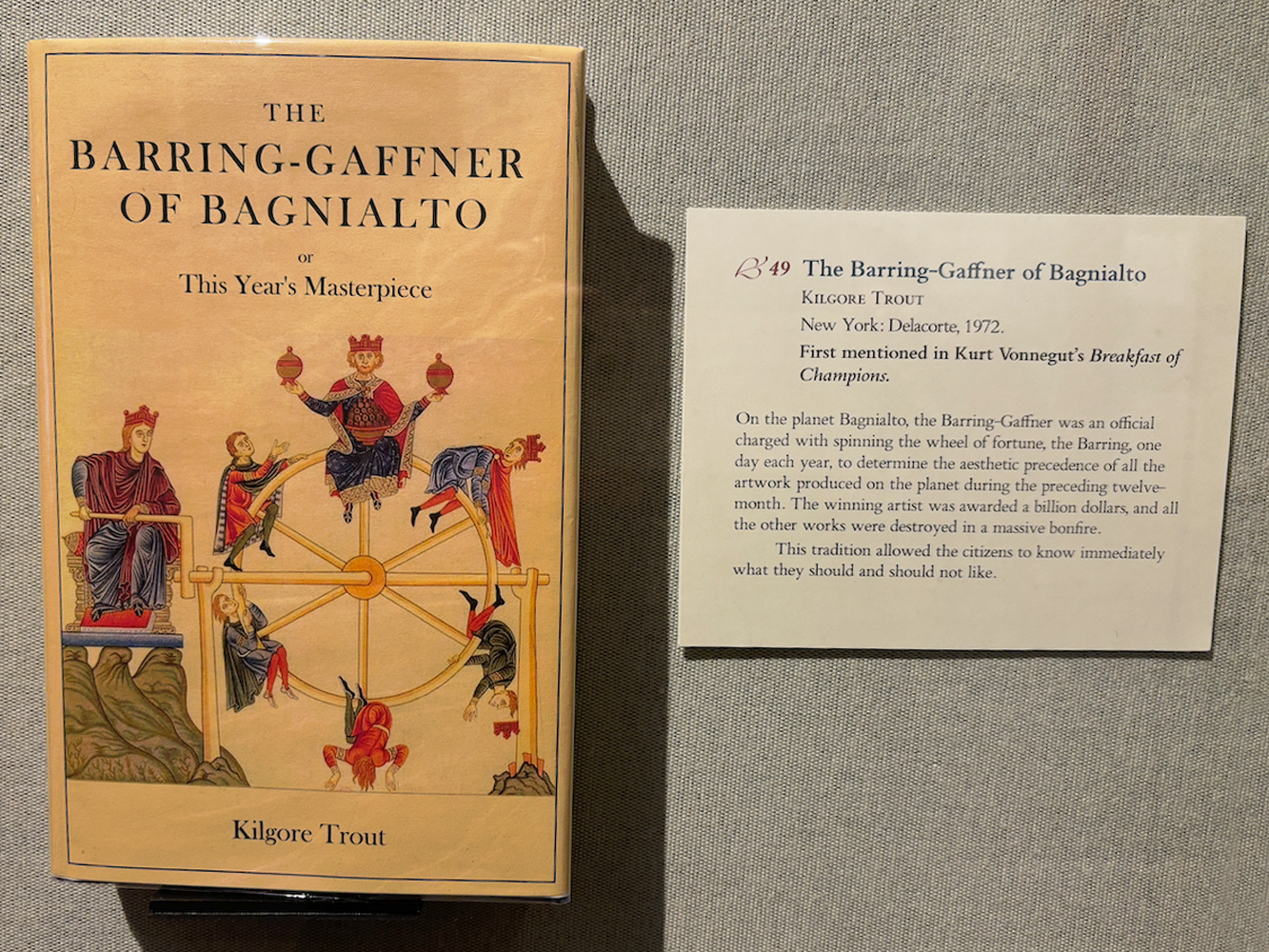

Manhattan’s Grolier Club recently hosted an incredible exhibit that I was lucky enough to visit a week before it closed. “Imaginary Books” showcased physical copies of vaporous works from throughout the ages, all from the “collection” of bibliophile an Grolier Club member Reid Byers. This unique collection of nonexistent objects comes with an appropriately chimerical backstory involving Paris’s Club Fortsas, a fictional institution inspired by an actual hoax, “founded” by Byers’s equally imaginary great-great-granduncle, Jean Nepomucene Auguste Pichauld, Comte de Fortsas.

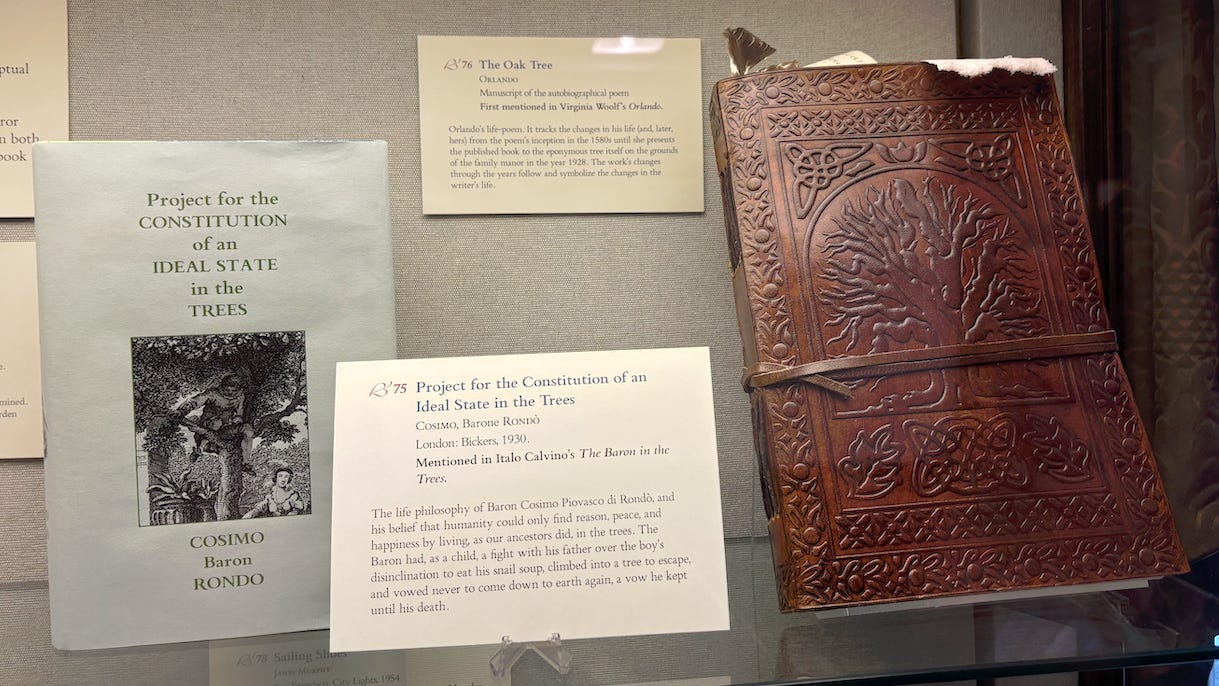

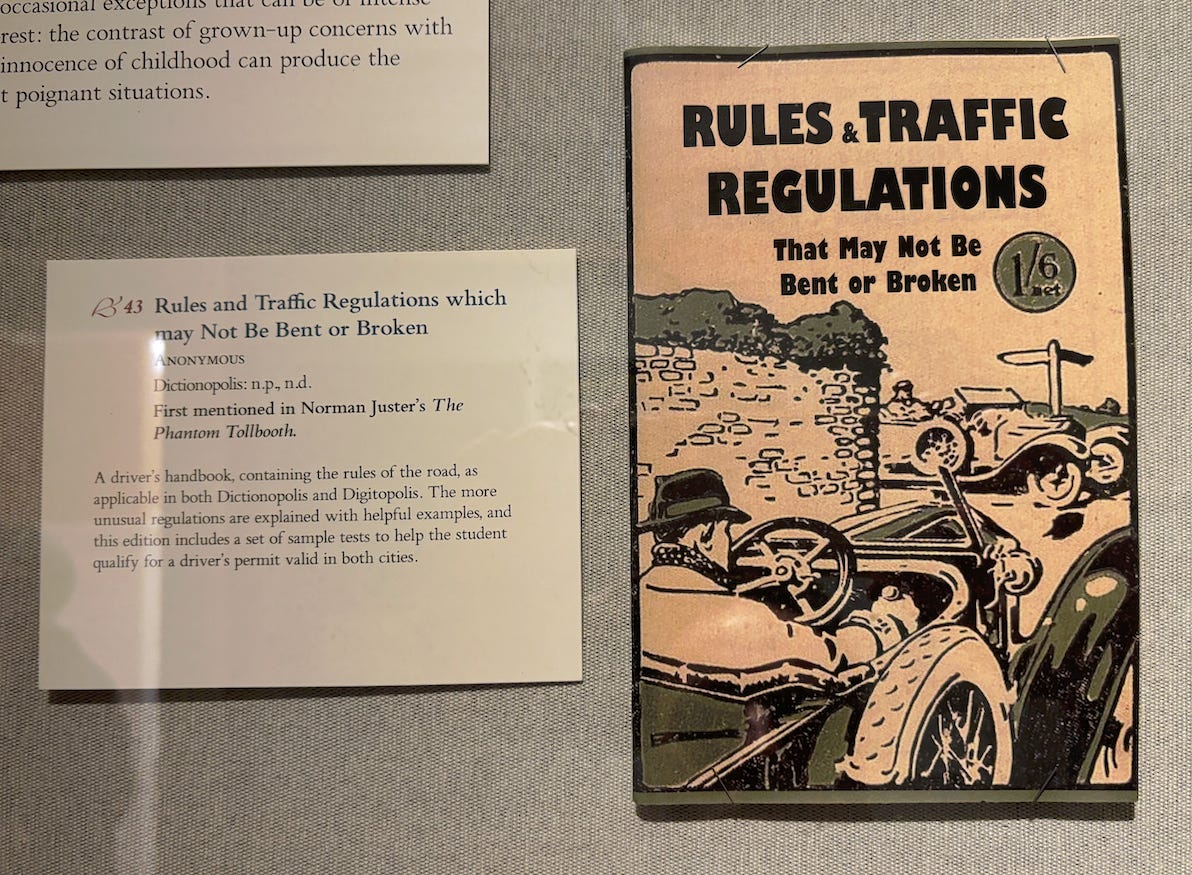

While the exhibit had much to enjoy on a conceptual level, it was made achingly evocative by the craft and imagination that went into the project’s execution. Supported by a select group of master craftspeople, Byers has brought dozens of titles from the obscurity of oblivion to the material world. As painstakingly designed embodiments of literary potential, they bring the ethereal to life in funny, clever, enlightening, and occasionally creepy ways. The sense of mystery is only enhanced by displaying these volumes behind glass, leaving you to wonder at all of the words and images that lie implicit between their carefully weathered covers, which represent not only the stories they purport to hold, but the stories they originally arose from.

Byers categorizes the works under three headings:

Lost Books (which once existed, or are believed to have existed, but have vanished without a physical trace)

Unfinished Books (which were conceived of or even partially written by authors before being abandoned to time)

Fictive Books (which were created entirely within the context of other books)

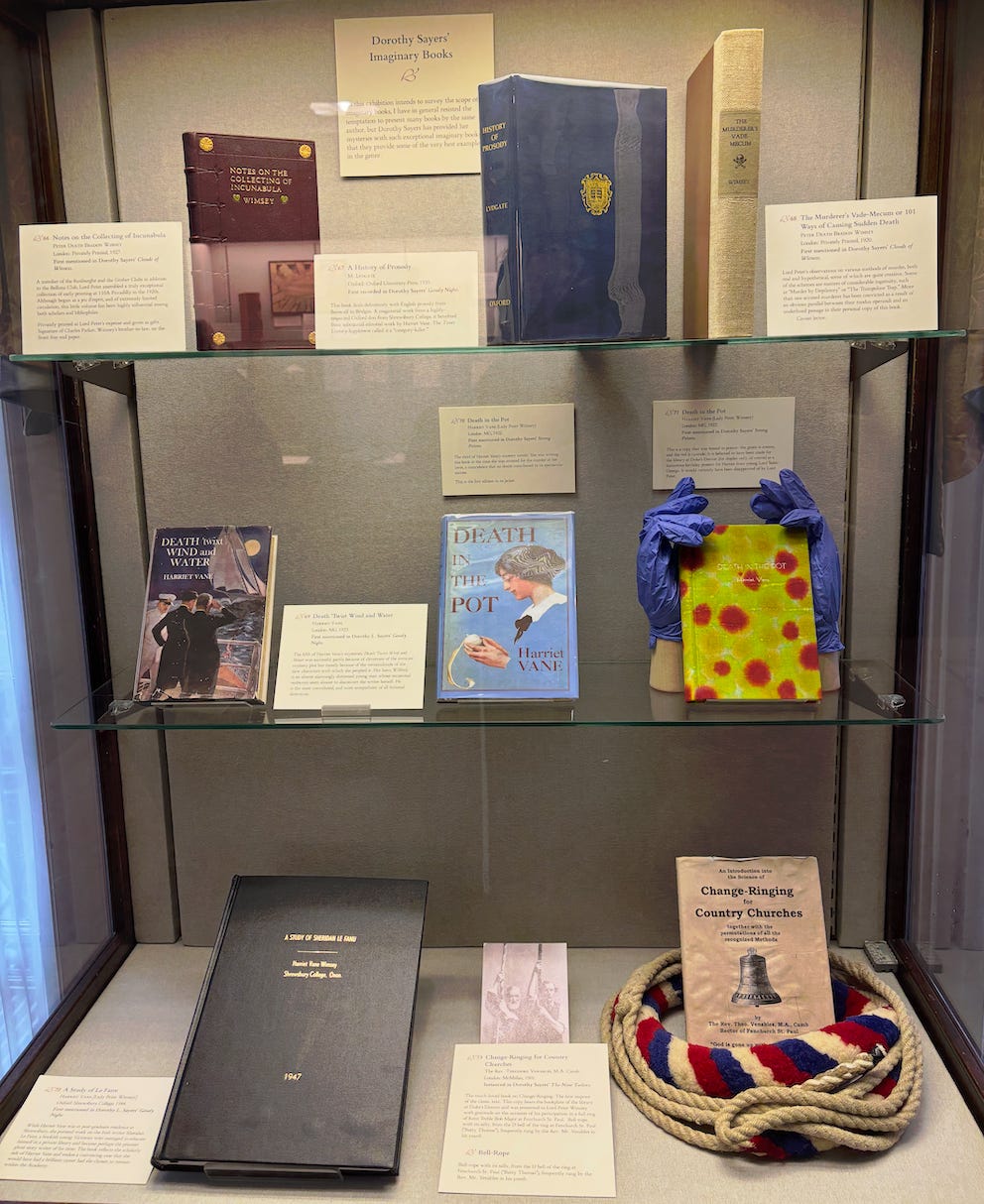

These three categories unfold across history, ranging from a 1920 copy of Homer’s lost comedic epic the Margites through a digital tablet holding The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (the guide itself, not the 1979 novel named after it), replete with towel. In between are categories ranging from “Fictive Non-Fiction” to “Imaginary Mysteries,” including a full cabinet devoted to imaginary books conceived by Dorothy L. Sayers.

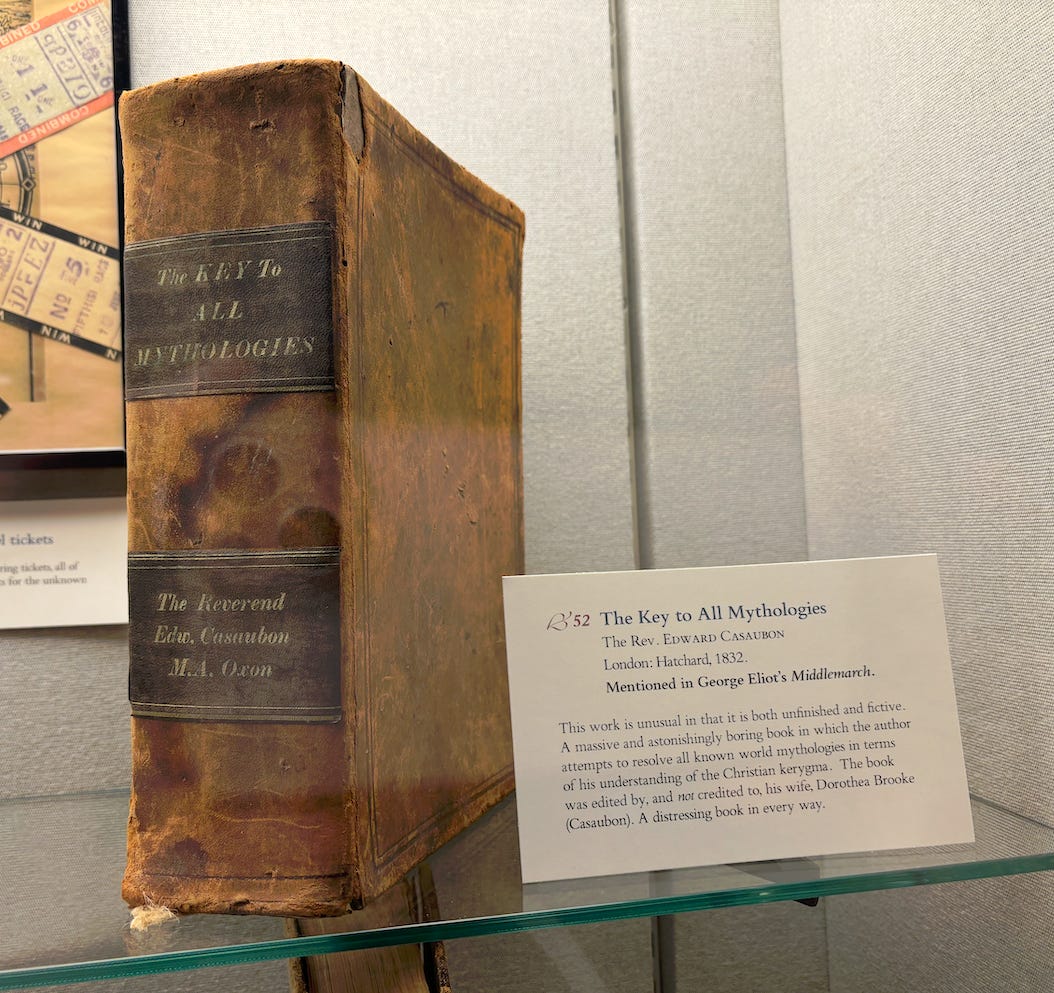

Hope and I attended the exhibit with our friends Trav and Carolyn, and we carried on giggling like precocious schoolchildren the entire time. Look, there’s Mr. Casaubon’s dreary tome The Key to All Mythologies from Middlemarch!

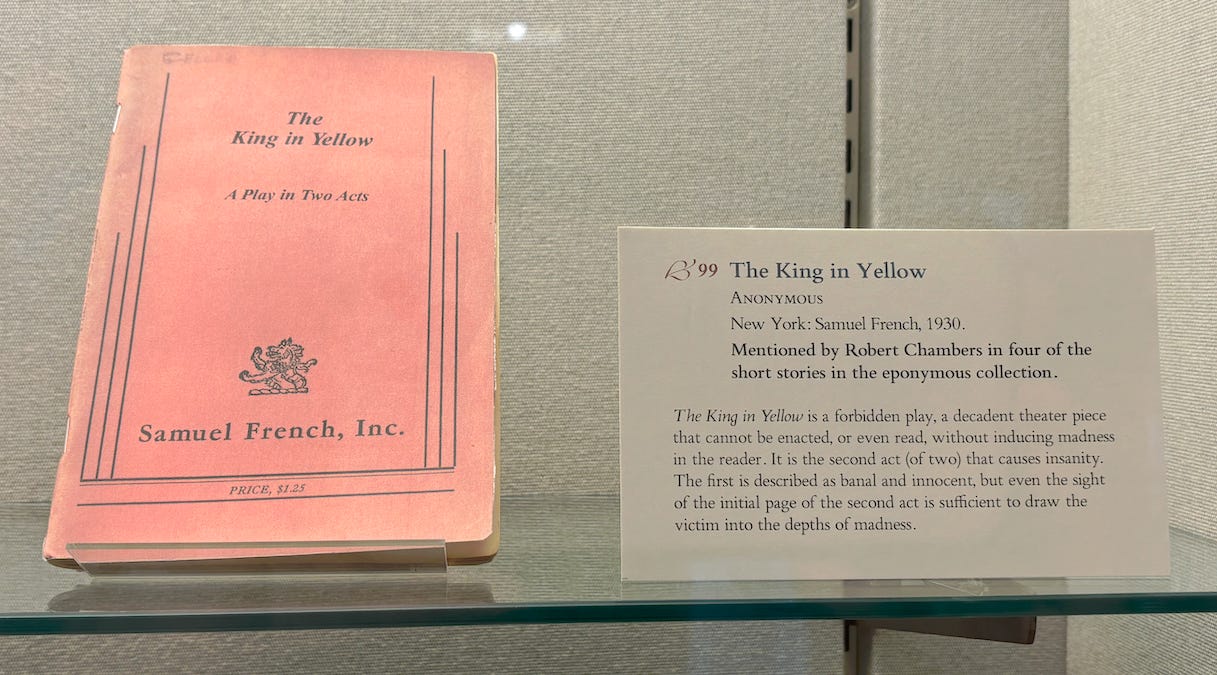

Over here - a Samuel French actor’s edition of The King in Yellow, a fictional play that drove readers and audiences irreparably mad! (I’ve seen a few of those in my time.)

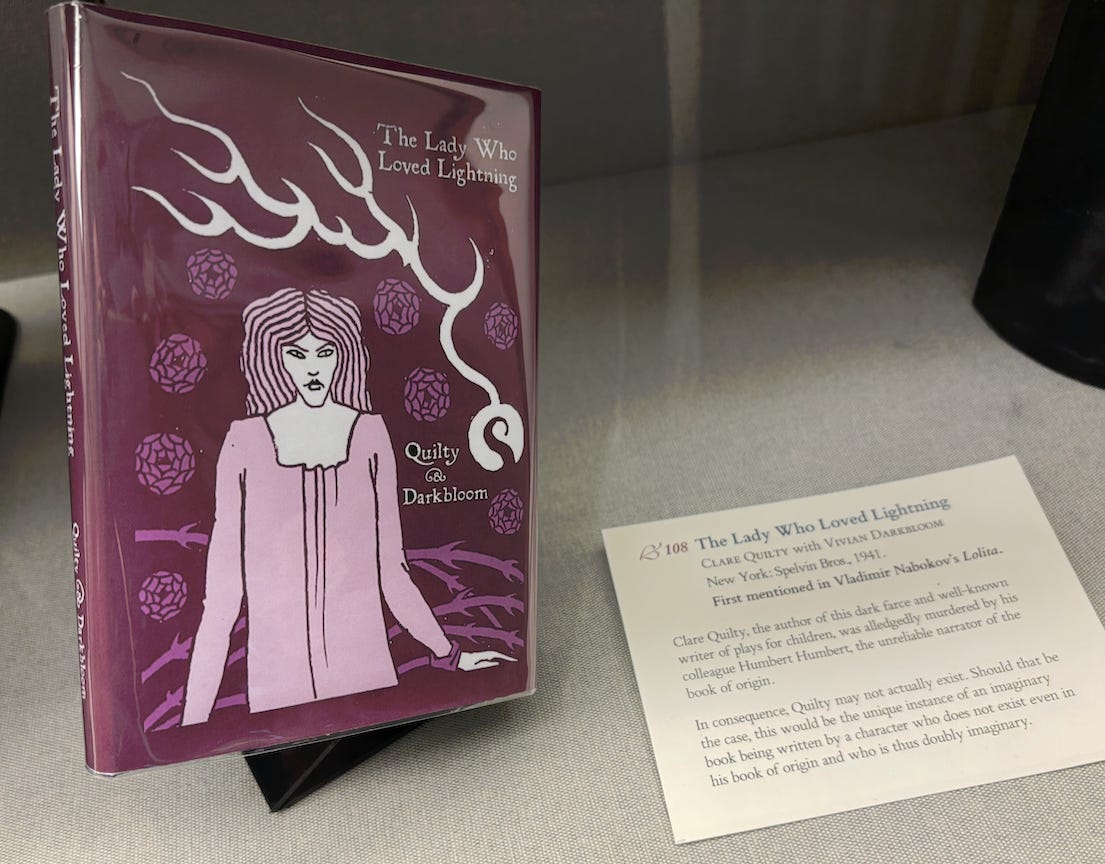

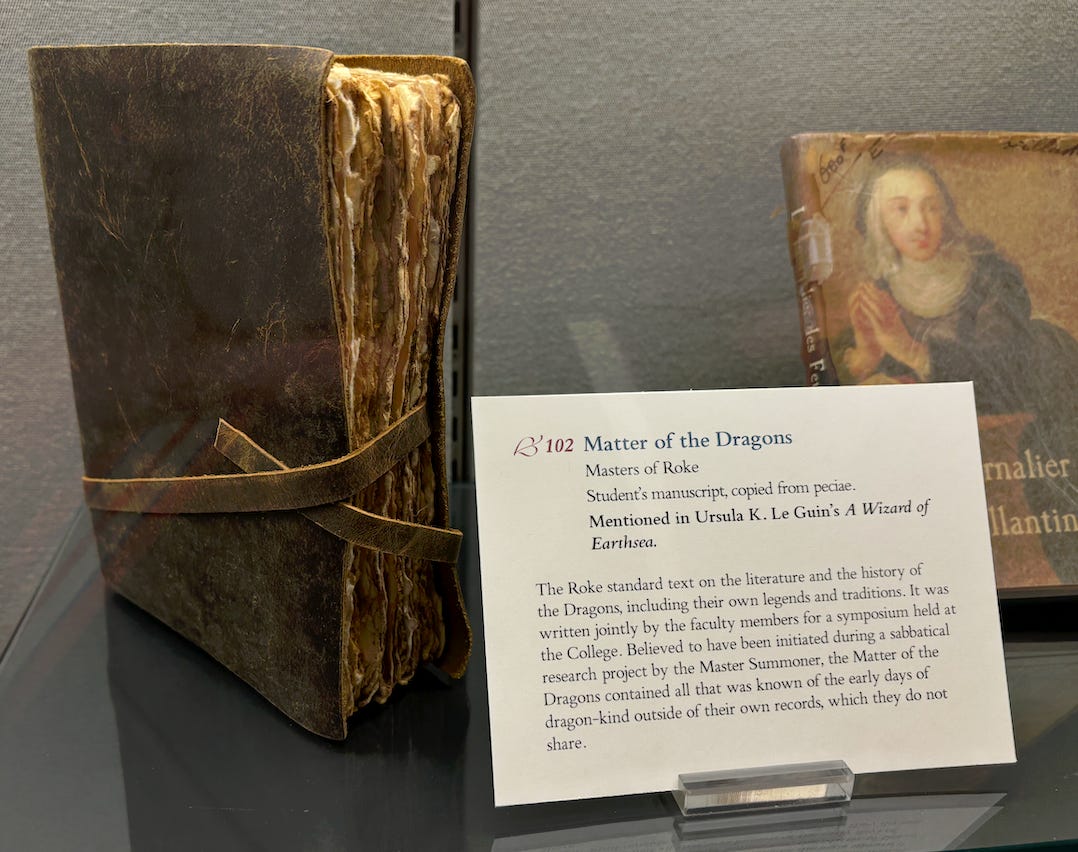

So many books I’ve read about but never read. It’s like all of my favorite authors came to a costume party dressed as their own deep cuts. Nabokov! Le Guin! Borges! Vonnegut!

I was so transported by the exhibit that I dropped some change for a copy of the catalog. (Don’t worry - if you’re not as insufferably print-obsessed as I am, you can view the exhibit online in perpetuity.) The book comes equipped with a half-dozen tongue-in-cheek introductory essays that provide deeper background on the parodic Club Fortsas, its history, and its members, along with more detail on the collection and its antecedents.

Paging through the book over the past few weeks has made me wonder why the imaginary books within its pages have even more pull than the books on my own shelves. I have several theories, some of which are explored within the book itself:

Everyone loves a mystery. The unknown has potential that the known can’t match. We’re hard-wired to be intrigued by anything that lies beyond our grasp. Since we’ll never know what these books are like, it’s impossible not to wonder.

These books don’t disappoint. Few things are worse than something that doesn’t live up to your expectations. Since the best book is always the next one on your list, these titles will never let you down. They’ll always be as incredible as you wish.

They’re at home in my dreams. I’ve written before about how I dream up imaginary books almost every night. So vivid at the moment, their memory drifts into mist the moment I wake up. By capturing the surface of similar dreams, this project gives me a glimpse into my own unconscious.

It’s the thrill of the hunt. The only thing I love more than reading books is finding and buying them. There’s no joy greater than scanning the shelves at a used bookstore for a treasure that I’ve long been seeking or an unlikely title I’ve never heard of. Imaginary books imply the existence of riches that we can constantly search for but never find - and isn’t that a metaphor for life itself?

With so much vivid, tangible, rot and evil unfolding in real time right now, it might feel awfully frivolous to spend so much time on what can be written off as literary parlor games. But at a moment like this, there’s something unbearably poignant about unfulfilled potential.

One of the book’s introductory essays (credited to an Elisabeth-Claude St. Martin de Beaurepaire of the Librarie Contes de Fees in Strasbourg but I suspect, like the others, penned by Byers himself) is called “The Uses of Fictive Books: A Checklist.” It delineates 34 different reasons why anyone would conjure or invoke an imaginary book, replete with illustrative examples, under headers like “To Entertain” or “To Argue.” Two in particular struck me as urgent:

To produce critical doubt: The Rise of the Colored Empires in Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. As Antoinette Lafarge said, “Fictive art produces complicated forms of doubt and pleasure. Doubt is one of the chief shields against authoritarianism or that narrowing of thought that leads to doctrinaire thinking.

To raise awareness in readers that not everything they read is real or true: Goldstein’s The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism in George Orwell’s 1984. This is especially important during periods in which deception and lies are considered acceptable forms of discourse. Seldom in the history of the world have they been so pervasive as at present; never has it mattered so much.

In other words, imaginary books can serve as vaccine against bullshit, introducing a harmless amount into our system to help us solidify the boundaries between what’s real and what’s not. The result has the potential to enrich both sides - shoring up our belief in the world as it is while enriching our ability to envision what it could be.

I run hot and cold about the inherent value of imagination, which can be employed by forces both good and ill - just look at the creative energy that’s currently being poured into the dismantling of our 250-year-old democracy. But it’s far easier to destroy than to build, and I’m enough of an artist - enough of a child - to feel exhilarated by the paradox of doubt as a key to harnessing imagination for good.

Ultimately, to dream of imaginary books is to dream of better worlds, and this is part of how we stay alive. Yes, we need to act in the world, with all the ugliness and compromise and tedium that entails - but we also need to keep that sense of potential alive inside of ourselves. For all their whimsy, imaginary books connect us to the infinite, where they can help us see the possibilities this world seems bent on denying.

I wish there were even more of them.

The Samuel French printing of King In Yellow is brilliant.