Every time a new Wes Anderson movie comes out, the discourse takes a similar trajectory. Professional critics and Letterboxd reviewers alike say, it’s okay, but the schtick is wearing thin. Not as good as his last one. This time it just didn’t hit for me. Et cetera. And then they go on to praise the earlier films to which they had the exact same reaction.

I’m the sort of fan who was going to like Anderson’s latest, The Phoenician Scheme, no matter what. I just enjoy spending time in his imaginative world, and there’s a significant part of me that has no interest in whether or not a given film is “good.” That said, I believe they always are, because Anderson is a sensitive craftsman and thinker who clearly seeks depth and resonance within the narrow (to some) limits of his interests and abilities. So I find it funny when people complain this his films don’t live up to their expectations. I guess they have a hard time seeing incremental but vital changes of focus and intent as significant. But just wait - after the passage of time or a second viewing does its trick, they can start to see it for what it is. I mean, Shakespeare’s plays all sound the same if you’re not really listening, right?

So yes, I have a very specific bias. But I really do believe The Phoenician Scheme offers an interesting new wrinkle in Anderson’s work, and one that’s more suited to the present moment than a caper comedy set in an imaginary 1950s might appear at first blush.

A very common refrain of Anderson criticism is that he’s insufficiently political. His allegedly twee little worlds are little more than hermetic and carefully crafted reflections of privilege. I don’t think that’s true at all - even putting aside the fact that The Grand Budapest Hotel is explicitly about the rise of fascism. Much like the glorious screwball comedies of the 1930s, Anderson employs a level of cinematic poetry that takes the follies of the rich (or at least the successful) as a jumping-off point for flights of daring imagination and deeper human truth. But I’m sure Anderson fully recognizes this sentiment toward his work, and it appears that The Phoenician Scene seeks to address it - but in a way that seems calculated to frustrate the people who level such criticisms in the first place.

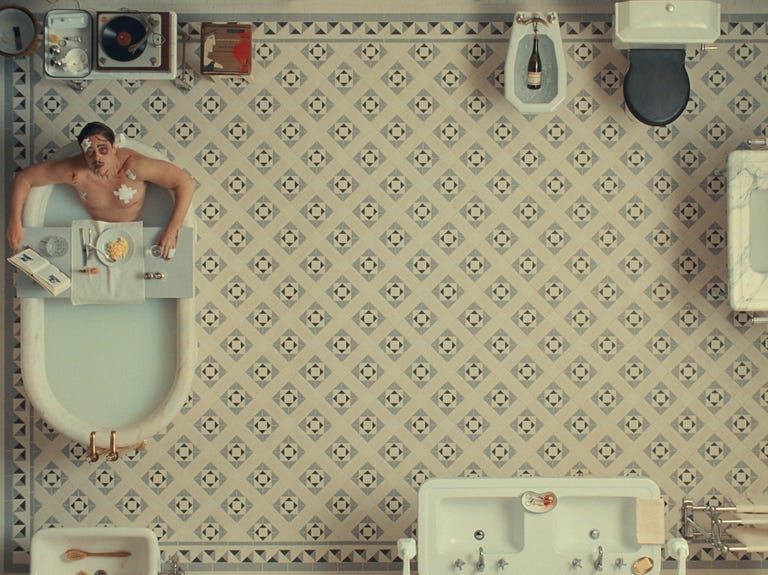

The posters for this film might as well read “Benicio del Toro IS Capitalism!” The character he plays is an arms dealer and international oligarch named Zsa-zsa Korda, Hungarian by birth but stateless by design, all the better to keep his vast empire of riches safely out of government reach. Korda is immoral, rapacious, and unstoppable. Survivor of an endless succession of airplane crashes and assassination attempts, he’s a literalization of the quip, attributed to Frederic Jameson, that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

But most insidiously of all, Korda is charming. His endless self-confidence and skill at eleven-dimensional chess lend him an insouciance that’s nearly impossible to resist. His stature as an Anderson protagonist is nearly metafictional, displaying a sense of advance planning that, combined with creative risk-taking, becomes downright seductive. Del Toro is so infernally watchable, and directed with such verve and grace, that it’s impossible not to enjoy him. Capitalism can clearly deliver the goods - so why question it?

Where Korda and Anderson part ways is at the point where this sense of style requires the pitiless exploitation of other humans. The titular development scheme at the film’s center is a multi-tiered construction project slated for the fictional Middle Eastern country of Phoenicia. This nigh-impossible gambit is about 90% MacGuffin, designed to expose the plot to an array of colorful backers played by A-list actors greatly enjoying themselves. But one sticking point keeps surfacing - the scheme’s successful completion requires a certain amount of slave labor. Korda shrugs it off at first, but his daughter - and the film along with her - refuses to let him off the hook.

Korda’s next of kin, Liesl (Mia Threapleton), is a novitiate nun on the cusp of taking her vows when she’s called into her remote father’s presence and informed that she is to be the sole heir to his incomprehensible fortune. Her skepticism confounds him and ultimately draws them together, as his materialism smears into her spirituality and vice versa. He undergoes a series of biblical dream sequences clearly inspired by Sergei Paradjanov’s The Color of Pomegranates, which it took me until now to realize is a clear influence on Anderson’s iconic (in the sense of Eastern Orthodox religious icons) presentationalism. Accustomed to snaking through all obstacles, Korda discovers that he can’t weasel out of having a soul.

Rounding out the story’s central trio is an entomology-tutor-turned-administrative-secretary named Bjorn (Michael Cera), who is lured into the story by another of Korda’s sneakily appealing attributes: his insatiable and genuine curiosity. Korda is a man who wants to know - in order to make a buck, sure, but also because he can’t help it. He consumes knowledge like he consumes resources, in order to generate more, more, more. As with Liesl, Bjorn’s disinterested love of science becomes compromised with exposure to Korda - though a third-act twist enjoyably muddies the metaphorical waters. Still, Bjorn’s feeding of Korda’s passions leads us to wonder about the purported moral difference between craving knowledge and craving material goods. Is science for its own sake nobler than science applied to civilization’s ends? And if civilization is inherently violent, what then? These questions rattle around in the film’s luggage compartment like the crate of brightly painted hand grenades Korda carries around to dispense as favors to his potential allies.

That the film finds its way to a happy ending of sorts is potentially what will most enrage those seeking a clear political message. Korda is set up for comeuppance from the start, and he gets it, though not as hard as haters might wish. But this is where it becomes most clear that Anderson, for all the careful precision of his narrative approach, is no allegorist. These characters may carry heavy symbolic freight, but they are people, in the end, and they deserve to learn and grow the same as those of us on this side of the screen.

The humbling redemption of Korda ultimately validates capitalism with a small “c” in a way destined to disappoint the revolutionaries. But as in those ‘30s screwballs, the social order is sometimes upended on the most personal of scales. What choice do we have but to play the cards we’re dealt? Just as a capitalist can always eke out an extra buck, an optimist can always squeeze some pleasure out of life, however reduced. We should all be so lucky as to find ways to live our humble lives in a quiet corner of the system rather than letting the system define us. Maybe lowering our expectations is the first step to creating real change.