Keep an eye on your leg

This week's record of cultural purlieus traversed

Guys, I’m pulling back to one post a week. I imagine this might come as more of a relief than a disappointment. I’ve been enjoying this very much, but two posts a week don’t really allow me time for anything else, and there’s a bunch of other stuff I want to do.

This newsletter is nothing if not pliant. I named it “The Jeff Stream” because I imagined it as a flow of ideas and words and images that run through whatever channel I carve for it. So I guess we can just consider this a narrower channel. Maybe it’ll run deeper? Ha!

In case it’s interesting (and I mean, if you’ve followed me this far it’s on you), I have three projects on my docket right now that I really want to spend more time with:

A second episode of The Nerve, the ball for which has already begun to roll

A third issue of Congress of the Monsters, to accompany the second issue that is SO CLOSE to being printed

A short film script that I’m part way through writing

And these are just the “small” projects! I have a hundred other projects of all shapes and sizes that excite me, but which I feel I lack the time and energy to pursue. The newsletter has accomplished its initial mission, which was to get me back into the habit of writing regularly. Now that I’ve built up some momentum, it’s time to diversify a bit. The good news is you’ll hear WAY more about all of this stuff whenever the time is right.

Last weekend we visited the Whitney with our friend Kristen. We caught very different shows by two fascinating artists, both of which shared the same floor.

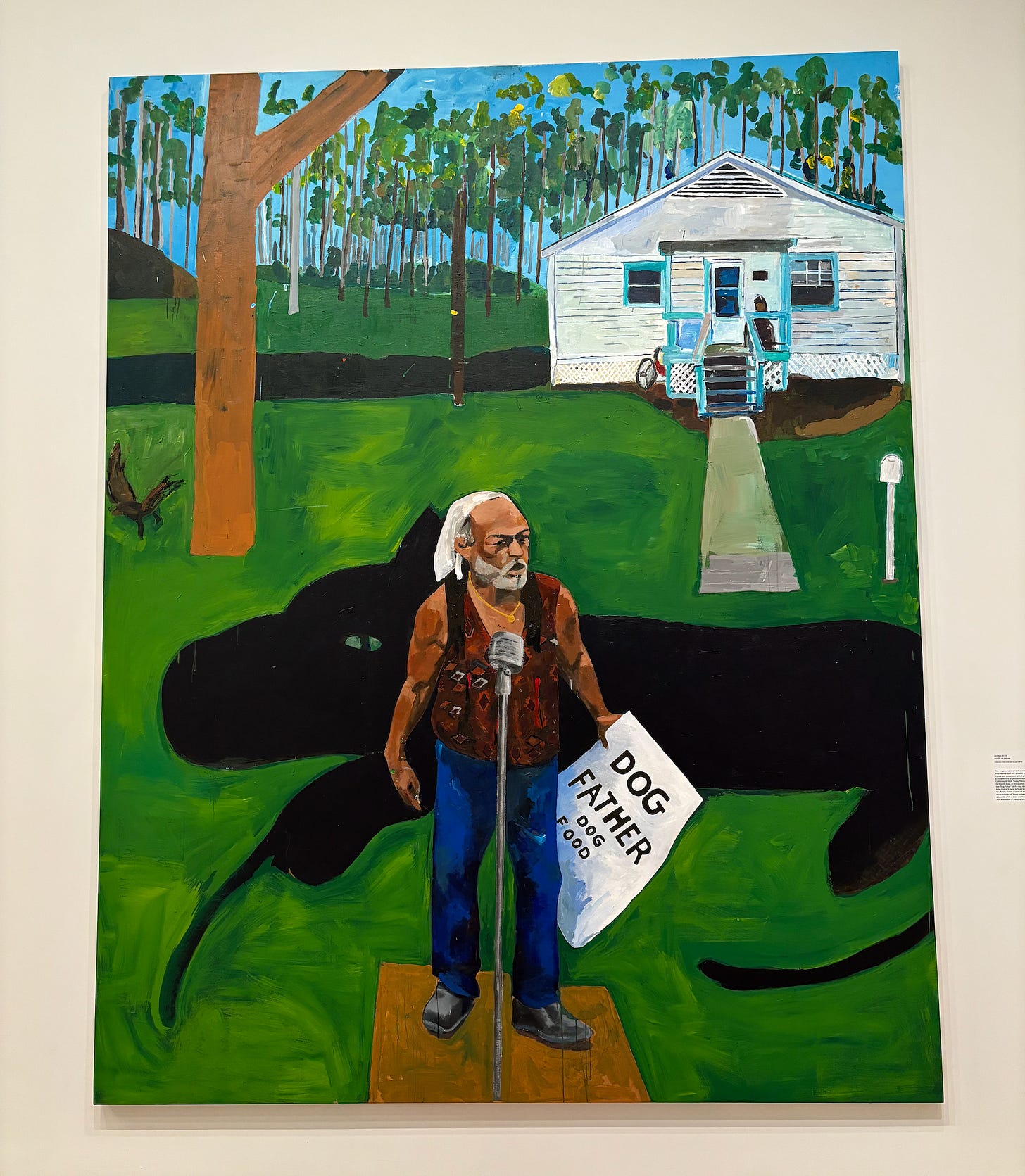

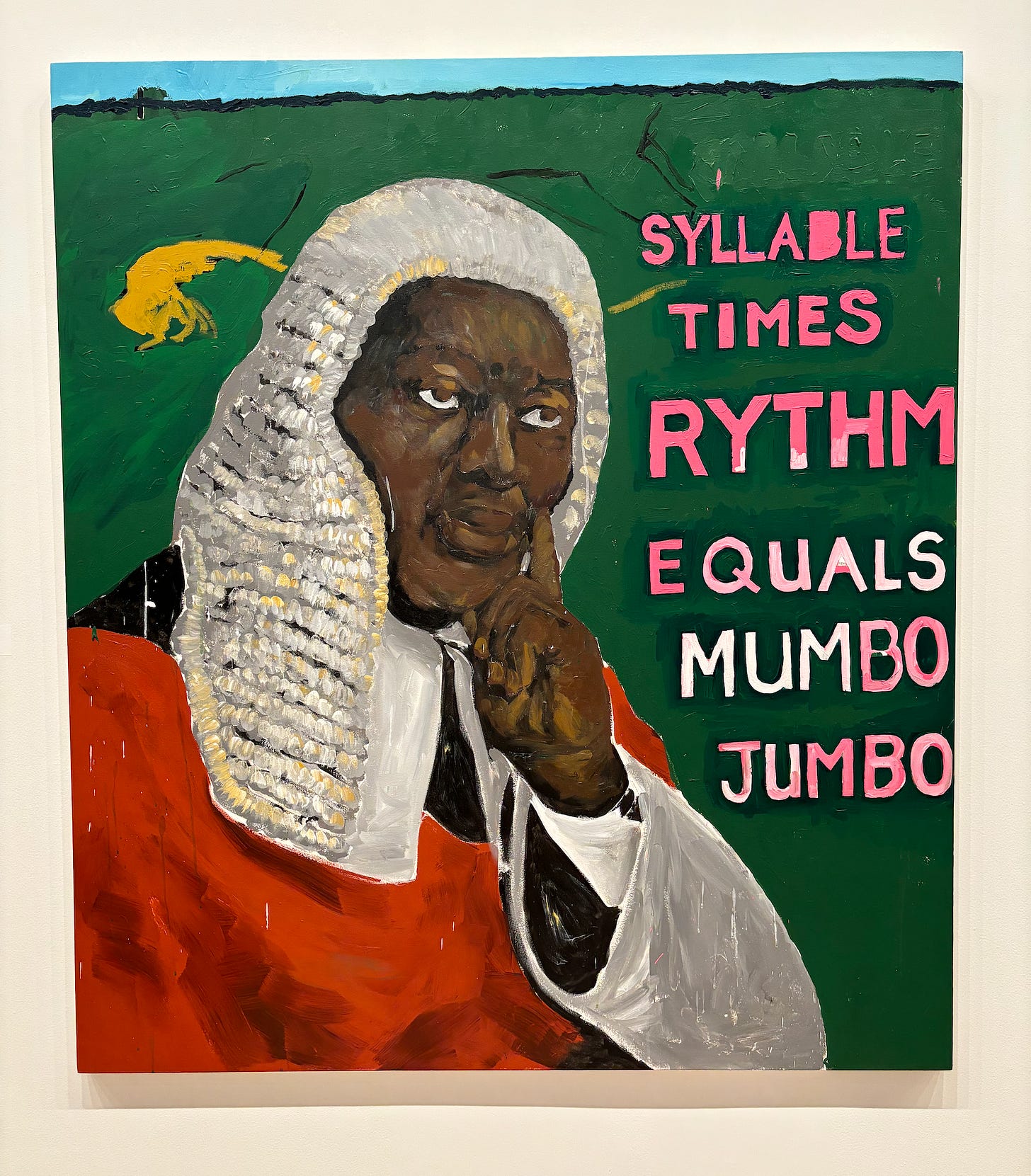

Henry Taylor is a Black American painter who brings a loose, improvisatory approach to his monumental figurative canvases. The result is excitingly unnerving, like seeing an awkward outtake from deep in your camera roll on the cover of a coffee-table book.

Born in 1958 as the youngest of eight children, Taylor is both a late Boomer and a late bloomer, whose long road to art stardom brought him through 10 years as a psychiatric technician and a Bachelors degree in his late 30s (he lacks an MFA, bless him).

These photos don’t do justice to the scale of his canvases, which dominate the room with a playful intensity. Yet their broad fields of color and carefully obfuscated details belie a deep emotion. Whether the subject is his love for his family, his rage at America’s institutional racism, or his pride in the achievements of those who made their mark on the system, there’s nothing cool or detached about his deceptively sure technique.

The result is an iconic style that I won’t soon forget. I wasn’t especially familiar with Taylor’s work before, but now I’ll recognize it any time I see it.

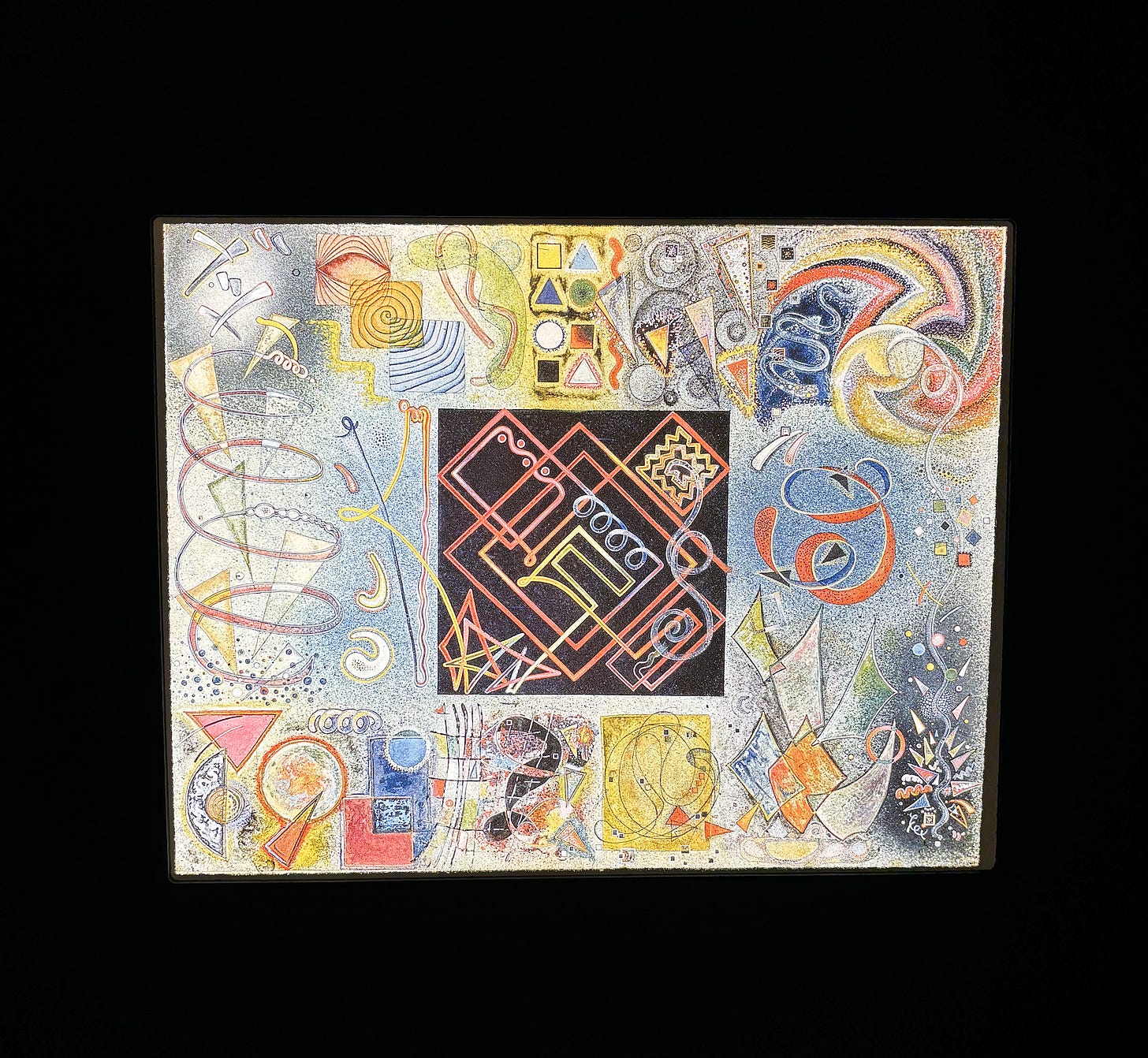

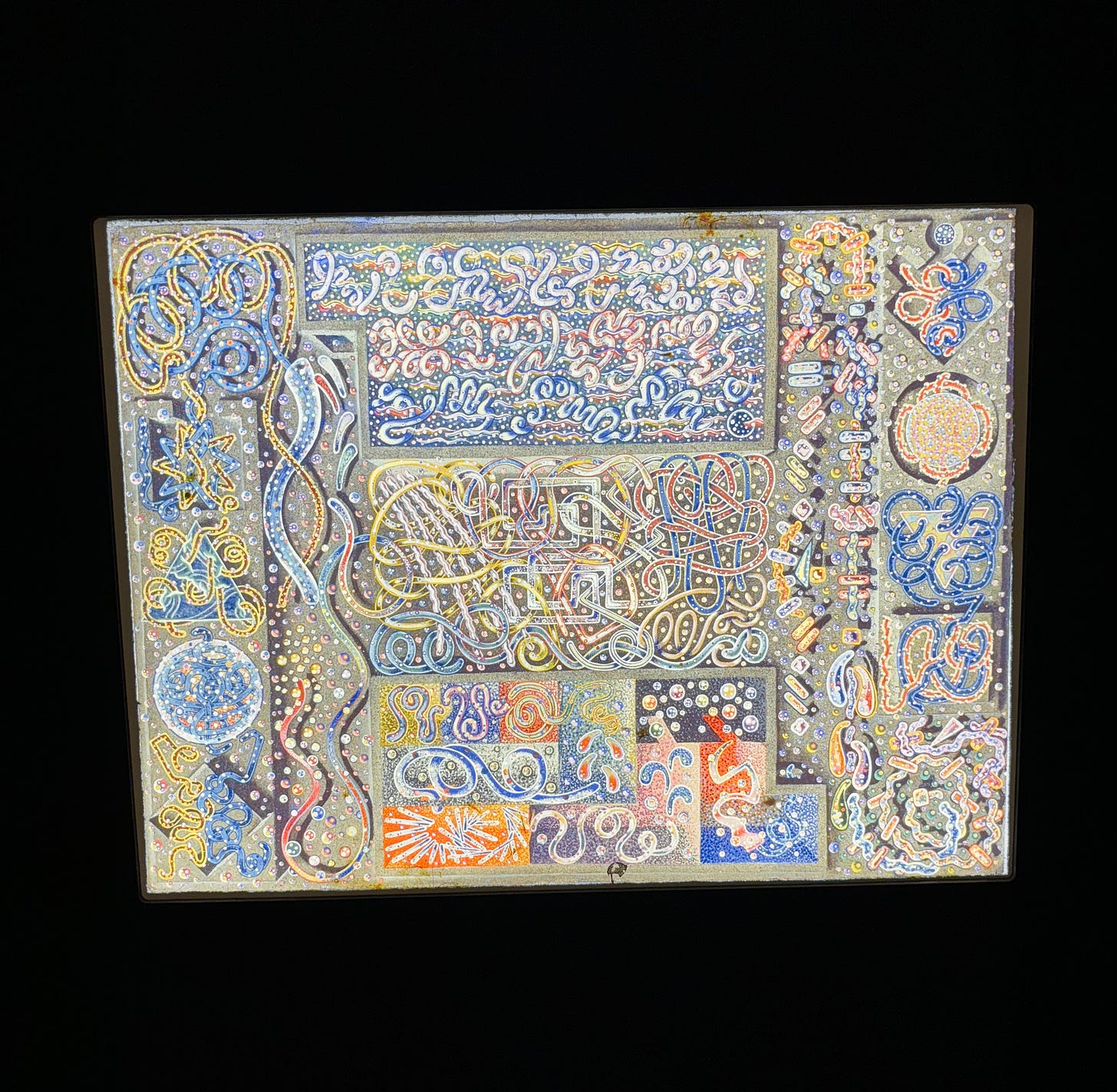

On the opposite end of the floor, at about half the size, was the exhibit that I’d initially come to see: a retrospective featuring the work of the weirdo mid-century polymath Harry Smith.

I came to Harry Smith through his Anthology of American Folk Music, a legendary feat of musical curation that first enchanted me about a quarter of a century ago with its mystique of the old, weird America. But the Anthology turns out to be just the tip of the wizard’s staff.

The exhibit features what seems to be a little bit of everything. A four-screen film installation featuring a cornucopia of imagery set to the strains of Brecht and Weill’s Mahoganny. A more intimate screen projecting stop-animation made from Victorian paper cutouts (Terry Gilliam avant la lettre). Lightbox projections of lost paintings painstakingly composed to align to specific jazz recordings. Abstractly mystical prints. Designs for a consumer tile business. Anthropological recordings. Paper airplanes.

Many of these objects were tiny, gnarled, and heady, in complete contrast to Taylor’s dreamy, sensual grandeur. It was harder to walk through and easily grasp what a “Harry Smith” looked like. And yet, that puzzle was part of the pleasure. A mind and a body of work composed of scraps. What does it all add up to?

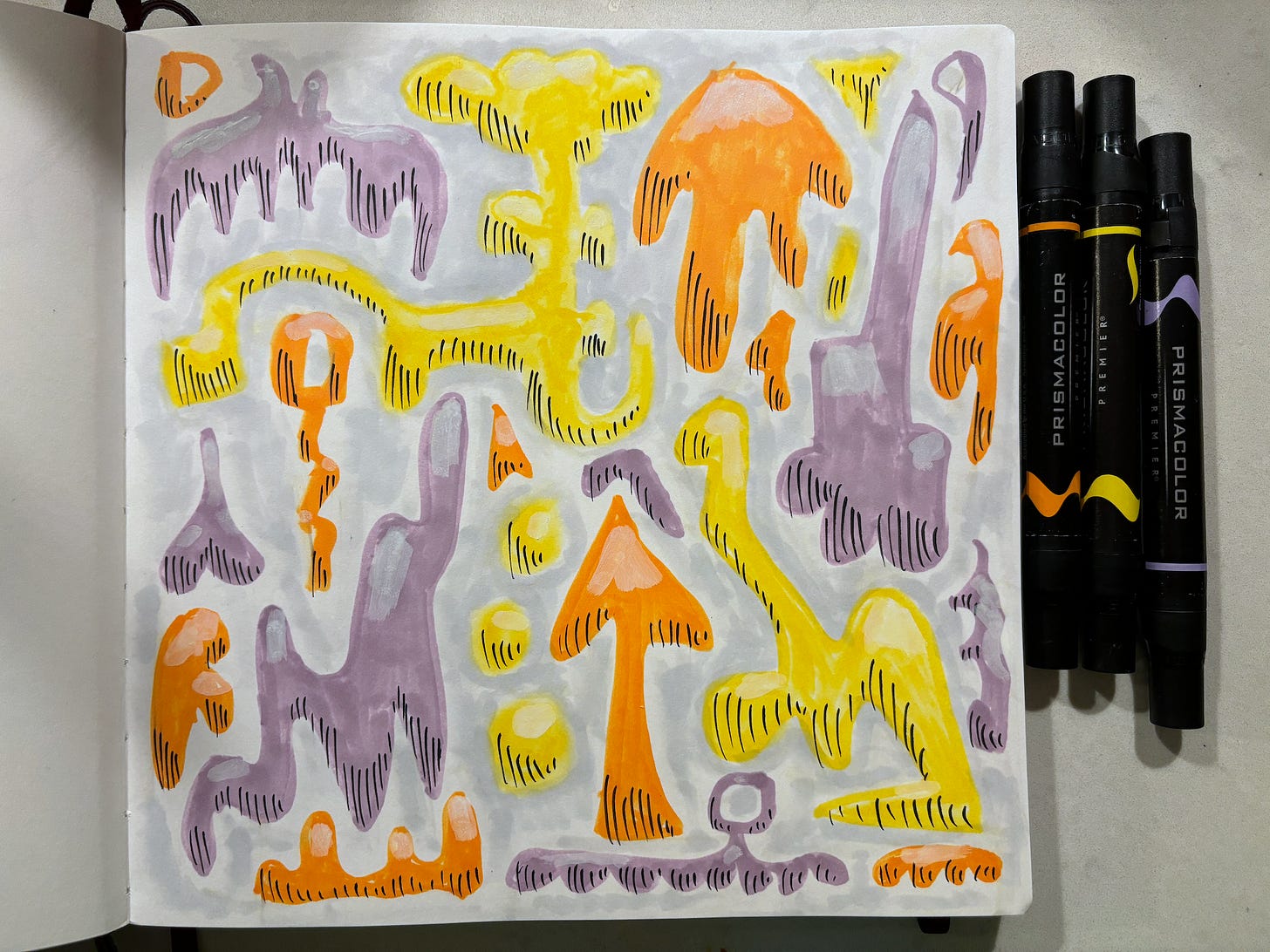

While I admire Taylor’s work, Smith’s is, for all its gnomic obscurity, more relatable to me. I’m a magpie - I follow my curiosity in incoherent directions, and all I have to show for it is a collection of disconnected scratchings and scrawlings. I don’t share Smith’s ambition to serve as a kind of post-industrial shaman, but I understand his attention span.

The existence of these two exhibitions side by side on the same floor of the Whitney is a fascinating study in contrasts. Two vastly different, but equally valid, ways to be an American artist (a male one, at least). One three times the size of the other: Taylor’s large paintings stark against the whitewashed walls, looming over the crowds; Smith’s works huddled against black and gray walls in the dark, with only the work itself illuminated. Grand statement vs. cryptic undercurrent, in a way that doesn’t track along the stereotypical boundaries of generation and race. This is the last weekend the shows will be open, so see for yourself if you can.

Whenever I discover unexpected parallels between two works of art that I just happen to encounter in rapid succession, I have to assume a large part of the similarity is an effect of my own projections. Sometimes, of course, as in the case of the Whitney shows above, it’s the result of curatorial intention. At other times, though, the coincidence is clearly the result of supernatural causes.

Last weekend, we watched two movies. On Saturday, we had long-standing plans to see Barry Lyndon screened at the Roxy. We’d never seen Stanley Kubrick’s three-hour costume epic, so when our friend Fred goaded us to join him, it seemed like the time was finally right.

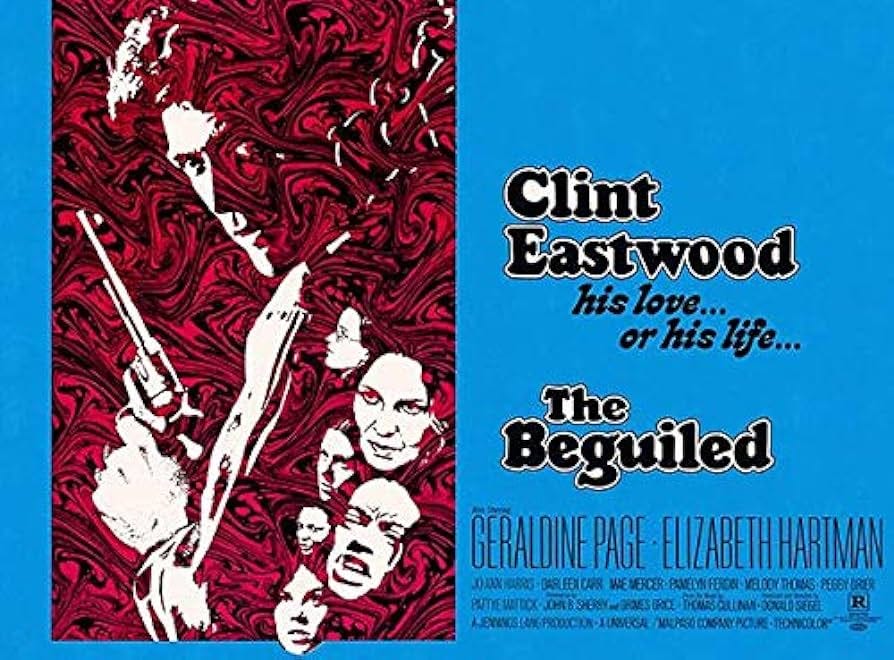

The night before, we were looking for something to watch on Criterion and saw that The Beguiled was leaving at the end of the month (the 1971 Don Siegel original, not the 2017 Sophia Coppola remake). Hope had been intrigued by this movie when she first heard about it a decade or so ago, so, once again, it seemed like the time was finally right.

If you’re familiar with both of these movies (which is another way of saying “spoiler alert”), you may recall that they have one thing in common. They are both movies about solipsistic men who are punished for their sins by having their leg cut off.

I mean, there’s a lot to be said about both films. Barry Lyndon is, to my surprise, my favorite Kubrick film by a long shot. I’ve never been a huge Kubrick guy, though I can appreciate where he’s coming from. It turns out the Roxy, where I’d never been, is a crummy theater: really bad sightlines that cast the head of the guy in front of me in a leading role; major sound issues that accompanied the first half of the film with the jazz band playing upstairs - don’t trust a hobby theater in a trendy hotel to provide a first-rate cinematic experience. I was really anxious about being stuck there for 200 minutes, but after about 20 I was all in. The film’s beauty softens Kubrick’s cynicism, and his cynicism sharpens the beauty. In the title role of an 18th-century Irish fortune-seeker, Ryan O’Neal is a feckless cipher, which works out just great because so is Barry. It’s a rags-to-riches-to-grinding-disappointment story that never quite takes the turns you expect it to, which somehow keeps you invested without giving anyone to root for. I’m surprised to find out that I’m looking forward to seeing it again.

By contrast, The Beguiled is gritty, ‘70s sleazeploitation dressed up in gothic, Civil War drag. Siegel’s Dirty Harry himself, Clint Eastwood, is a Union soldier injured behind enemy lines and taken in by the isolated denizens of a girls’ boarding school. Like Barry, he plays every angle he can to get what he wants but becomes a victim of his own hubris. His masculinity is a few slugs more toxic than Barry’s, revealing him to be more villain than antihero. As such, Siegel provides the sort of catharsis that Kubrick delights to withhold: Rather than lingering into an uncertain future, Eastwood’s character faces deliverance at the hands of several women just as pissed off at their own self-deceptions as at his more blatant lies.

But the kicker (ha!) is that each of them gets a leg chopped off, right under the knee, as the direct result of their own poor decisions. The freudian implications of this symbolic castration are more forcefully presented in The Beguiled, but in both cases the message is clear: moral integrity = bodily integrity. Don’t stick things there they don’t belong, fellas!

Anyway, The Beguiled is a compelling curiosity while Barry Lyndon actually turns out to be one of the greatest movies ever made. Now you know!

I don’t really have much to say about this music video from Japanese electronic duo group_inou, other than that it’s delightful. I first watched it projected onto our living room screen, but it reads even better on your phone, in what feels like an endless scroll of cheeky, sketchy manga/anime tropes:

Culture, whether large or small, is a spectrum. Better to ooze across the gradients than huddle in just one corner.

Anyway, from January 24, 2016, here’s undoubtedly the greatest photo I will ever take.

Enjoy your weekend!