From lad to dad I've been glad about MAD

The most important publication in the history of human civilization

I was born in 1976, but my life didn’t really begin until 1983. I was with my mom in the supermarket checkout line when I saw a most peculiar magazine. The cover was split down the middle, with a Dracula on the left and a Yoda on the right. But there was something off about their faces - they were identically freckled, with too-wide grins, a missing front tooth, bugle ears, and an indescribably doltish stare. I had no idea what I was looking at, but I knew I had to have it. My mom, bless her, gave in, and the course of my life was determined.

The magazine in question was MAD magazine’s Summer ‘83 Super Special: MAD Takes a 100-page (Gack!) Look at Horror, Sci-Fi, and Other Weird Things. It was a themed compilation of material from nearly 30 years of satirical skewering that charted the path of post-war American culture with loving derision. It featured parodies of things I knew (Star Wars, Superman) and things I didn’t (The Exorcist, ecological catastrophe), all of which revealed a world of gauche, snickering delights that my mom quickly regretted giving me access to. Little did my six-year-old self know, but by opening it up and poring over its pages throughout the following weeks, I was being initiated into an aesthetic and worldview that would armor me with the irony, skepticism, and humor I would need to survive into adulthood.

Last weekend, I had the opportunity to steep in this funky brew for a few blissful hours as a visitor to the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA. This is where you can go through October to binge on the greatest art exhibition yet devised by the human species, “What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of MAD Magazine.”

The Rockwell Museum does a great job carrying the torch for illustration as an art form - a few years ago, we attended a wonderful exhibit there of fantasy art, featuring the likes of Frank Frazetta, Gustave Doré, James Gurney, and dozens others. But there’s a more direct connection with MAD than you might expect. Not only did the magazine put great effort into lampooning the sort of established media outlets like the Saturday Evening Post that were Norman Rockwell’s bread and butter, they were also fans. In 1964, editor Al Feldstein contacted Rockwell to paint the “definitive” portrait of MAD’s mascot, Alfred E. Neuman, who had already been interpreted by dozens of artists in multiple forms. Rockwell politely demurred, but claimed to be flattered by the request.

MAD has always been famous for its visual overload, with jokes crammed into every corner of every panel. Will Elder, one of the original MAD artists, referred to this penchant for maximalism as “chicken fat” - the secret ingredient that adds indulgent flavor to any dish. Visiting the Rockwell show is like doing the backstroke in a giant bowl of chicken fat - the fly in the soup, it turns out, is you, so prepare to drown in the most delicious way possible.

MAD’s writers and editors receive a lot of credit (and blame) for being key contributors to the sophomoric, tear-it-all-down attitude of cultural contrariness that may or may not have led to the American public’s current inability to even pretend at moral seriousness. Their intentions were unquestionably high-minded - they were a crew of subversive progressives reacting against 1950s conformity and repression by savagely mocking everything in sight. And it worked! For a while, at least, until the goobers decided they were in on the joke, rather than its butt, and irony died its umpteenth death.

But the Rockwell show does a brilliant job of establishing the one thing the Usual Gang of Idiots took more seriously than anything else: their craft. Whatever your taste in humor, you can’t deny that every page of every issue of MAD in its golden age(s) was a demonstration of artistic magnificence. Like an Algonquin Round Table for imbeciles, MAD attracted the best eyes and hands of its time to provide a torrent of visual delights unmatched by any publication of the 20th Century. I’ll fight you on that.

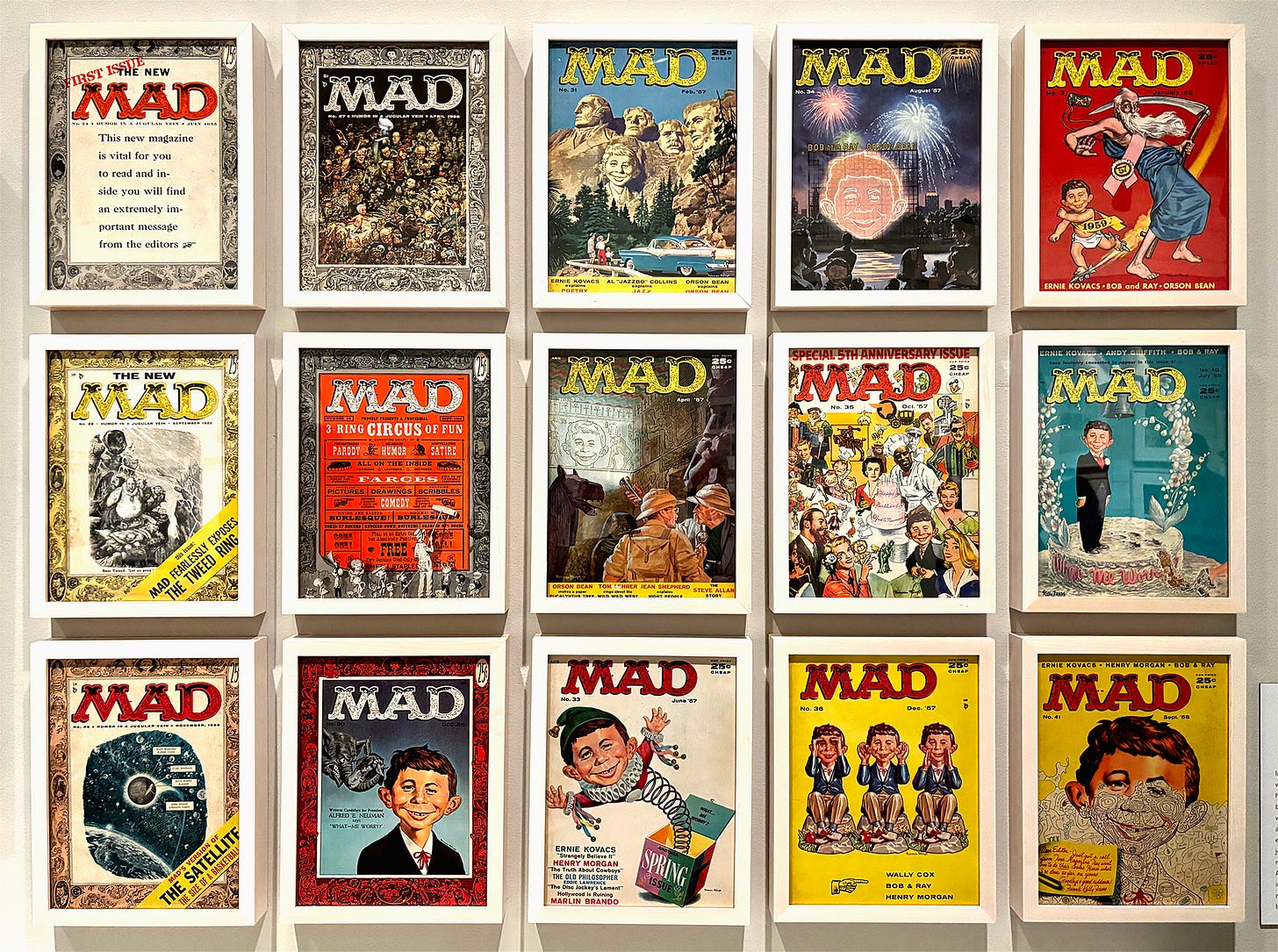

The exhibit starts out with MAD’s genesis as a comic book. For its first 23 issues, MAD was a full-color phantasmagoria that dragged every popular storytelling genre through its own exuberant mud. Under the editorship of Harvey Kurtzman - who wrote everything, provided layouts, and drew several iconic covers - MAD was an offshoot of EC Comics’ stable of horror and sci-fi titles, often mocking its own product as vociferously as its funnybook competitors’. Some of MAD’s best artists - Elder, Jack Davis, Wally Wood - had one foot in each of EC’s worlds, enriching both in the process.

Alas, EC was caught in the crossfire of the 1950s moral panic about comic books and shut down after getting dragged into punitive Congressional hearings spearheaded by well-meaning but asinine psychologist Dr. Fredric Wertham. Rather than submit to the indignities of industry self-censorship, publisher William Gaines closed up shop, discontinuing most of EC’s titles but relaunching MAD in a new magazine format that wouldn’t elicit the same scrutiny as the comic incarnation. Kurtzman left, bringing most of the original stable with him, but new editor Al Feldstein brought a more expansive if less virtuosic sensibility to the title. This is the MAD most people of my generation are familiar with, featuring black-and-white parodies of specific movie titles and showcases for idiosyncratic talents like Don Martin, Al Jaffee, and Sergio Aragones.

One of these later stars, who warrants an entire room of his own at the Rockwell, is Mort Drucker, the master caricaturist whose film and TV parodies scream MAD magazine to people who have never even opened an issue. I could write an entire essay about each of these guys - and yes, they were all guys, another reflection of the previous century’s small-minded shortsightedness, which stings a bit more coming from folks who should have known better. But this was an institutional failure, not the fault of any individual artist, and I’ll love each of them - how else? - madly until the day I die.

MAD continues today, in its way. A whole raft of latter-generation artists have temporarily called it home, and while it’s rarely reached the heights of its earlier incarnations, there’s always something to enjoy. After Gaines’ death in 1992, MAD became more tightly reined in by its corporate overlords, DC Comics and Warner Brothers; after decades indelibly representing its native city of New York, it made an ill-advised move to Los Angeles in 2018 and endured a flashy reboot that made many longtime readers go “Yecch.” Today, MAD is little more than a nostalgic retread, with new covers wrapped around more reprints of old material, but we subscribe anyway, and the whole family enjoys giving it a look.

The thing is, I THINK in MAD magazine. When I’m reading, I imagine characters as being drawn in the distinctive styles of these artists - Davis or Elder or Wood. My memories of movies often don’t involve what I actually saw on screen, but Drucker’s take on a character or a shot. I find myself walking through life like an Al Jaffee character, with a stolid center but balletic limbs and pointy feet, thrilling to a sensation of capitalistic joy the moment before I step in a pile of poop. Spy Vs. Spy, Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions, the Lighter Side - these are all features through which I mediate everyday reality.

And presiding over it all is MAD’s mascot, the gap-toothed Alfred E. Neuman. An idiotic everyman, he turns up in endless guises, blithely oblivious to the insane world that lumbers around him. His “What, me worry?” catchphrase is the pinnacle of caustic cynicism, upending cultural norms through a patented combination of ignorance and mischief. Bystanders, like square parents, react with shock at his subversive antics, which only adds to his untouchable aura. Sound like anyone else you know?

And yet, I find myself pining more each day for Alred’s more innocent inanity. Alfred may be a dummkopf, a jester, a cretin, a dunce, but he’s never mean-spirited. He stumbles through a range of situations on MAD’s covers not to hurt anyone, but to demonstrate the absurdities our society is based on. However bad things get, he never stops smiling. He always survives to grace another issue.

Any MAD memories of your own? Any interest in a deeper dive on any of these artists? Anybody reading this far? Lemme know!

Not long after my mother married my stepfather, I saw him come home holding a MAD magazine and I thought, "This guy's alright!"