Last Saturday night I read Jules Feiffer’s graphic novel Amazing Grapes. Marketed to middle-grade readers, it’s an unrelentingly strange fairy tale about an exploded family, with all familiar signposts removed. I wondered at the ability of its author/illustrator to continue surprising readers at the ripe age of 95. I did not yet know that he had died the previous day.

Almost everyone I know had something to say last week about the passing of David Lynch, an enduring cult figure who improbably attained the status of icon and prophet. The tributes to Jules Feiffer, on the other hand, have looked like a puddle next to Lynch’s raging sea. It’s a pity, because Feiffer was an artist who captured his own zeitgeist as broadly and resonantly as Lynch - he just didn’t have the dubious luck of dying at the height of his reputation. I love Lynch’s work, but Feiffer’s lives more deeply under my skin.

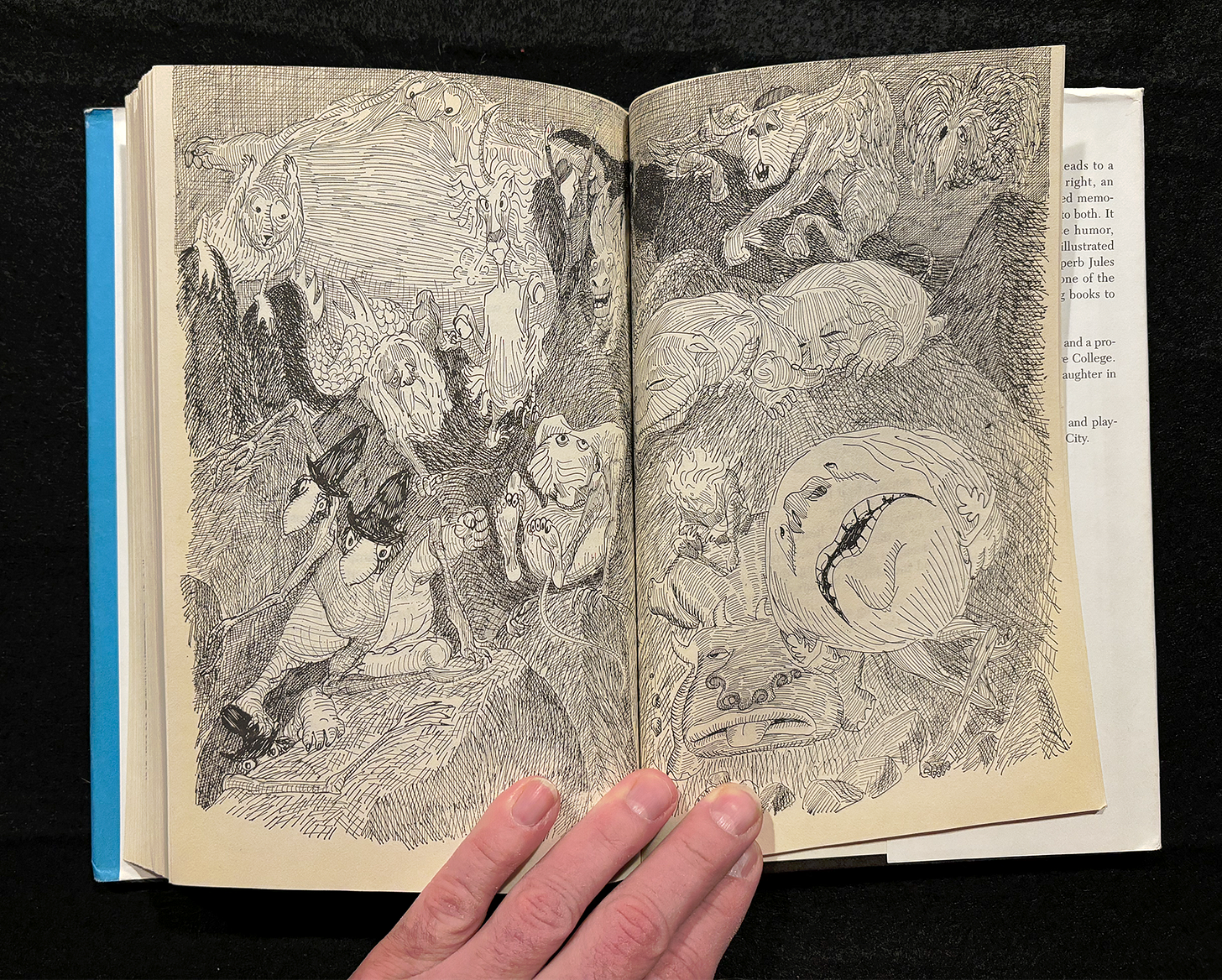

If not for Amazing Grapes, I don’t think I’d have seen much overlap in these two men’s respective oeuvres. But Feiffer, who frequently splashed around the edges of surrealism, went all in on this final work. Its suburban milieu cracks open to reveal netherworlds of occult import, nightmares filled with parents and authority figures that conceal multiple selves. Innate goodness is tested and, while it survives, a certain innocence is lost - the ending seems happy enough, but it carries with it a mass of unresolved contradictions. It veers from funny to scary to breathtakingly sad, sometimes across a single page. I have no idea if Feiffer was familiar with Lynch (who dabbled in cartooning himself), but he was certainly responding to a similar world.

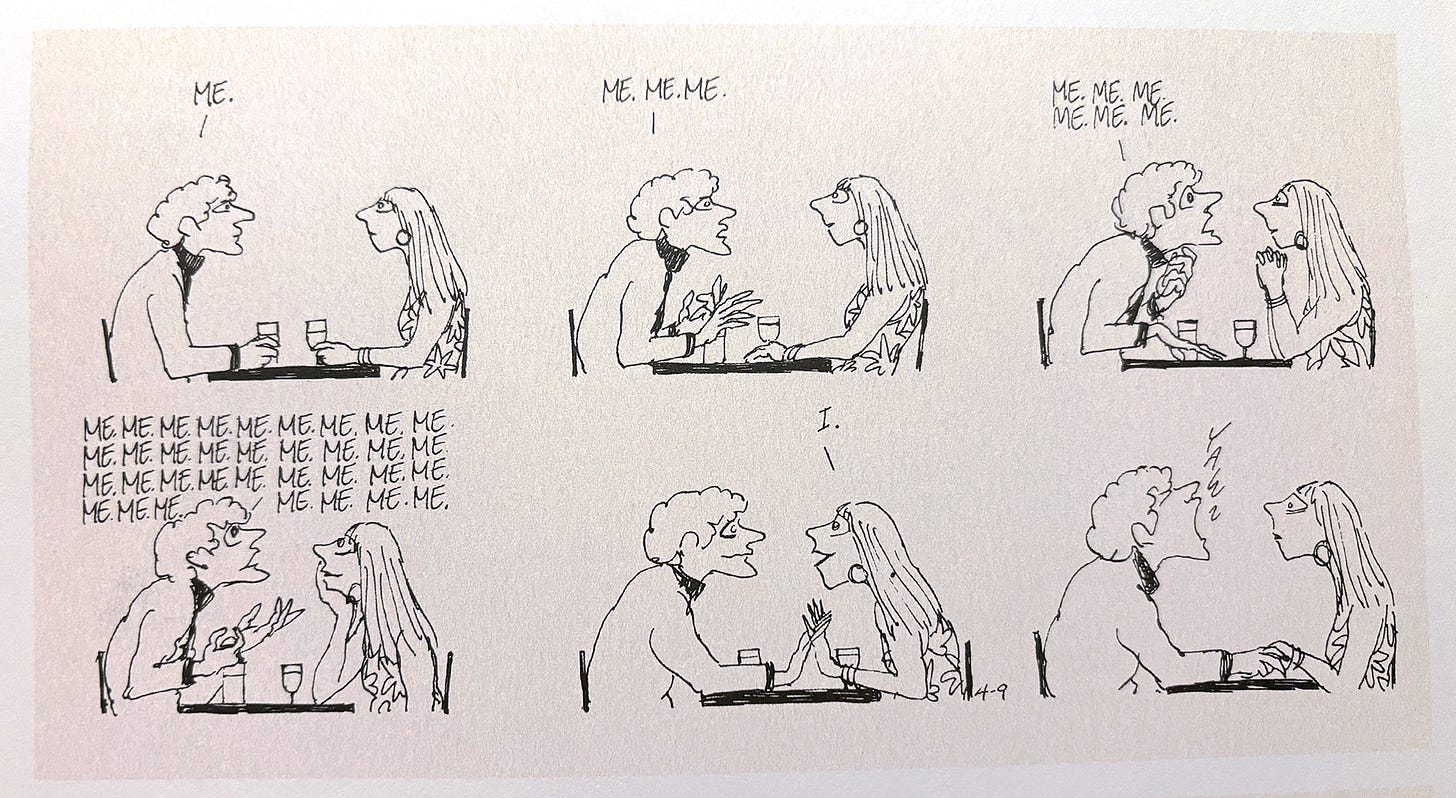

But that’s where the resemblance ends. While Lynch was gnomic and allusive, Feiffer’s genius was for pitch-perfect elaboration. Despite his skillful hand with images, I long saw him as a writer foremost. The Village Voice strips that earned him fame are characterized by their verbal wit and penetrating insights to the cultured milieu of the postwar decades. But beyond Feiffer’s enviable articulation, I’ve grown to appreciate - even adore - the indelibly scratchy minimalism of these images. He places his characters against a blank white background that might as well be called Feifferspace, where they have nowhere to hide from the hypocrisy and cowardice of their words.

You could hardly tell from the Voice strips’ visual sophistication that this was a guy who grew up as a superhero superfan and would go on to write one of the first seminal works of comic-book history, The Great Comic Book Heroes; his work took him far from his inspirations. And yet he started his career supporting that quintessentially dynamic visual stylist Will Eisner on The Spirit, and then went on to be a pioneer of the graphic novel, beginning with his first “novel-in-cartoons,” 1979’s Tantrum. For the final three decades of his career, Feiffer focused primarily on a series of watercolored children’s books that culminated in Amazing Grapes.

In fact, my first conscious encounter with Feiffer’s work was through his artwork for kids - specifically, his illustrations for Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth. This is what I cite most frequently when asked to name my favorite book - and how could I not? It’s about the entire world and how interesting it is. It was one of the first books I remember reading quickly, breathlessly, while walking into school from the bus. Juster’s wordplay and flights of allegorical fantasy were the main attraction, but Feiffer’s scribbly illustrations were a tremendous part of the appeal for third-grade Jeff. His clearly imagined figures and the mysterious scenes they imagine are sketched directly onto my brain.

It turns out he never liked those illustrations, which just goes to show how far you can trust artists. Maybe he saw himself as more of a writer too. After all, his most representative work is all talk - and I mean that as a compliment. It’s telling that his whitespace monologues and dialogues found a second life on the stage, both in an often-revived 1969 revue called Feiffer’s People (a production of which I produced at The Brick in 2012) as well as a series of well-received original plays and screenplays. Note that he never found success as a straight novelist - his work centers the voice, and I believe that it requires some sort of visual factor - either his deceptively simple drawings or the lively artifice of actors - to bring it to life.

In fact, my very first contact with Feiffer’s work happened through a film - though I had no idea at the time, because I was four. He was tapped by Robert Altman to write the screenplay for his Popeye film, which is one of those elaborate one-of-a-kind follies that help Hollywood executives feel justified in their conservatism. It was also the sort of movie that parents were fine plopping their kid down in front of when they got a free weekend of HBO, so some of my earliest memories consist of watching Robin Williams being held down and force-fed spinach before anyone understood that it would grant him superhuman strength. Whether this factored into my own eating challenges as a kid remains unknown, but in retrospect it’s an indication that Feiffer’s world is preoccupied with the effects of force, be it cultural, political, or, in this case, physical. Only a guy with a mind like that could have written something like Little Murders.

For all its charm, Feiffer’s work conjures an unsure world where everyone is preoccupied with status, generally at the expense of others. His characters are pulled inside out, with flagrant ids on proud display as whispering superegos ineffectually dither about the impression they’re making. My friend Trav S.D. lamented Feiffer’s death as the loss of “another link to the kind of America I believed in.” While I thoroughly agree, I also think his clear-eyed anatomization of American dysfunction is perfectly in tune with the current moment. Feiffer was always fiercely political, but even though he took on leaders like Nixon and Reagan head-on, he was unsurpassed at demonstrating the downstream effects of their mendacity on the minds of the humbler men and women of the middle class. The signifiers may have changed - fewer cocktail parties and more social apps - but the pervasive anxiety and solipsistic rationalizations remain the same. The blowhards who bend over backwards to justify their self-defeating votes for Trump, along with the hand-wringers who glory in their helpless outrage at the latest executive order - we’re all Feiffer’s people.

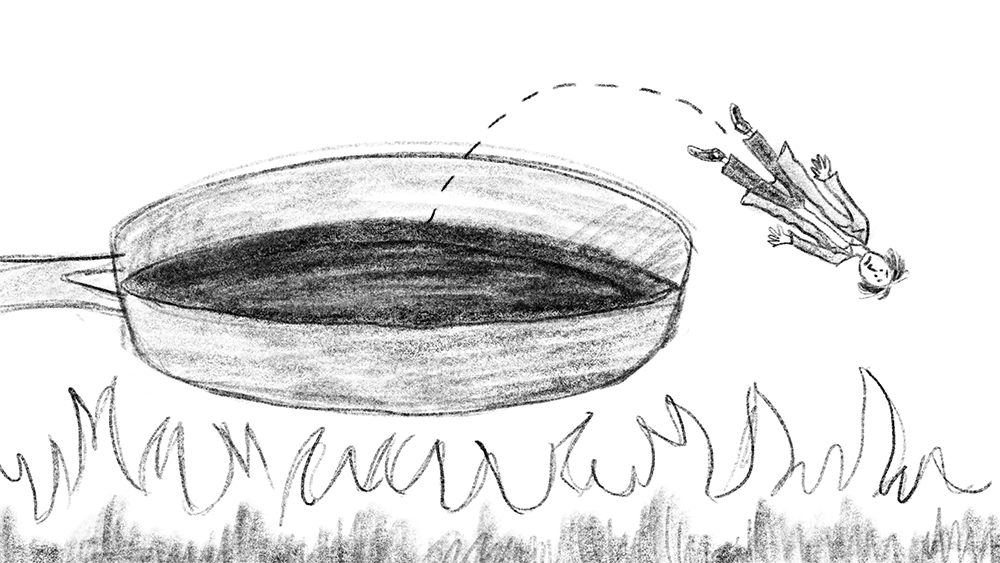

I had the opportunity to shake Feiffer’s hand 30 years ago, when he came to do a reading near my college. It was a tiny little bookstore in the country, and there were maybe two dozen people there in total. I wrote a little comic about that meeting when I performed in Bob Sikoryak’s Carousel series a few years back:

When I was in college, I had the opportunity to see Jules Feiffer read at a small bookshop in Tivoli, New York – there can’t have been more than a dozen people there, so I had an opportunity to strike up a conversation while he was signing my book.

I said, You’ve been a huge inspiration to me, Mr. Feiffer. When I was younger I wanted to be a cartoonist, and now I’m studying to be a playwright.

“Well,” he said, “You’ve managed to go from the world’s worst profession to one that’s even worse.”

In the end, I’m no longer much of a playwright or a cartoonist, but I carry the vestiges of both. Similarly, I’ll carry Feiffer’s enduring influence until it’s my turn to die. I even mean that literally - I was able to get his autograph that day, on my copy of the book he was promoting, A Barrel of Laughs, a Vale of Tears.

David Lynch may have gotten most of the headlines last week, but I believe Feiffer’s influence will prove just as enduring, if subtler. Lynch was a poet of the unconscious, but Feiffer was a student of our surfaces, with all the grimy comedy that entails. He brought his sensibility so many mediums across such a span of time, with such a sharp focus on what made the people around him tick - I hope they’re still talking about him in another 95 years. It’s not like people will be getting any less anxious.