Before the main narrative, here’s a reminder that my new little book, Congress of the Monsters #2: The Affair of the Pairs, is available to read and cherish! You can get your copy by coming to one of my Brooklyn readings on Wed 3/25 or Sun 3/30 (details here) or requesting a copy by post!

In the videotape format wars of 45 years ago, my family backed the losing side. For much of my childhood, a side room in the first floor of our house was dominated by a TV attached to a large, clunky Betamax VCR. Sure, the “Beta” (as we called it) was rumored to have a superior picture quality, but that’s not why we kept it around. It was simply a matter of sunken cost: Why buy a new appliance when the old one works perfectly well?

Alas, this folly kept us on the margins of the zeitgeist. Over a few short years, Betamax rental options from the local video shops dwindled down to nothing, leaving us few opportunities to watch the latest films unless someone brought us to a theater. Luckily, my sister and I became dab hands at taping programs directly off broadcast television, which we proceeded to watch in regular rotation for weeks or months at a time. We recorded the cartoon lineup every Saturday morning (The Snorks, Muppet Babies, Dungeons & Dragons) and watched it over and over again before taping over the following weekend. We wore out tapes of Christmas specials taped from prime-time television (Mr. Magoo, Smurfs, Pac-Man). We played random full-length films captured from TV as a kind of soothing backdrop to homework and daily chores (Annie, Big Business, The Facts of Life down Under).

There was one especially peculiar made-for-TV movie that we both spent countless hours rewinding and rewatching. She visited NYC last Saturday to see some friends and join us at the Women’s March, and that night, for the first time in nearly 40 years, we revisited it via YouTube. They just don’t make shit like this anymore:

(There’s a higher-quality version of this elsewhere on YouTube, but this is the one with the commercials, which makes it the rarer treasure.)

Alice in Wonderland debuted on December 9, 1985, with Alice Through the Looking Glass following the next night. I have no memory of watching them on the evenings of their original broadcast, but I certainly remember whiling away long, lazy hours with them over the months that followed. This was the first time I was exposed to most of the names involved, and it would be years before I connected them with anything else in pop culture. This makes sense, because by 1985 the vast majority of these people were well past the pinnacle of their fame, making this a crash course in the entertainment figures of a bygone age.

There’s Sammy Davis, Jr. as the Caterpillar. There’s Telly Savalas as the Cheshire Cat. There’s Sherman Hemsley as a mouse singing about hating dogs and cats, with Shelley Winters and Donald O’Connor flapping their fake feathers in the background. Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca, Jonathan Winters, Ringo Starr - an actual Beatle! Produced as a comeback of sorts by schlock impresario Irwin Allen - sci-fi TV producer and father of the ‘70s disaster film - the films both feature songs written by square hepcat and talk-show staple Steve Allen (no relation). I had no idea who any of these people were when I was nine, but what a delight it was to sit on the couch shouting their names out last weekend. My sister and I had no end of fun reminiscing about how little sense it all made, and how certain scenes and costumes and lines of dialogue have lingered in the back of our minds for decades. Foremost among them is Carol Channing’s bravura number from the second film (which we’re saving for her next visit):

The cultural phenomenon of Carol Channing was meaningless to me in 1985, but this scene still made an impact. This disheveled woman with her crazy voice singing about the unavailability of fruity preserves - followed by her terrifying transformation into a SHEEP - burrowed in very deep, and, when the clip went viral again a few years ago, we passed it on to our son Dash, on whom its infectious strangeness also left a pronounced impression. Rarely a week goes by when someone in our household doesn’t torture the others by bleating a baleful Channing impression to the tune of this song .

Dash actually decided to read Alice in Wonderland for a book report last year, and he struggled with the task of neatly describing its “themes.” “It doesn’t have any themes!” he said. “The whole theme is that there is no theme!” He ended up doing a great job with the idea that Rev. Dodgson was a logician playing with forms and that his book could be read as a subtle rebuke of Victorian conformity, but ultimately, I think he was right.

Alice in Wonderland endures for the same reason that it’s inspired so many star-studded adaptations. (There was also a 1972 British version with the likes of Peter Sellers, Dudley Moore, and Ralph Richardson, as well as a 1999 TV version with Martin Short, Whoopi Goldberg, and Ben Kingsley - all before Tim Burton’s creepily CGI 2010 remake.) The source material is perfect for this kind of nonsense because it is, literally, nonsense. Bringing these absurd characters to life requires not acting, but presence, making the outline of the original book a perfect vessel for celebrity. It almost doesn’t matter what folks are singing about, so long as they’re singing.

This very open-endedness makes it the perfect foundation for scores of disparate adaptations, from artsy (see Jan Svankmajer) to fartsy (just google around for porn versions - or don’t). Lacking a narrative agenda, Alice leads the way among the best children’s literature in its embodiment of pure play. Its movements are those of a child’s mind reacting with non-judgmental attention to the strange world that surrounds us. Who says something has to make sense to be meaningful?

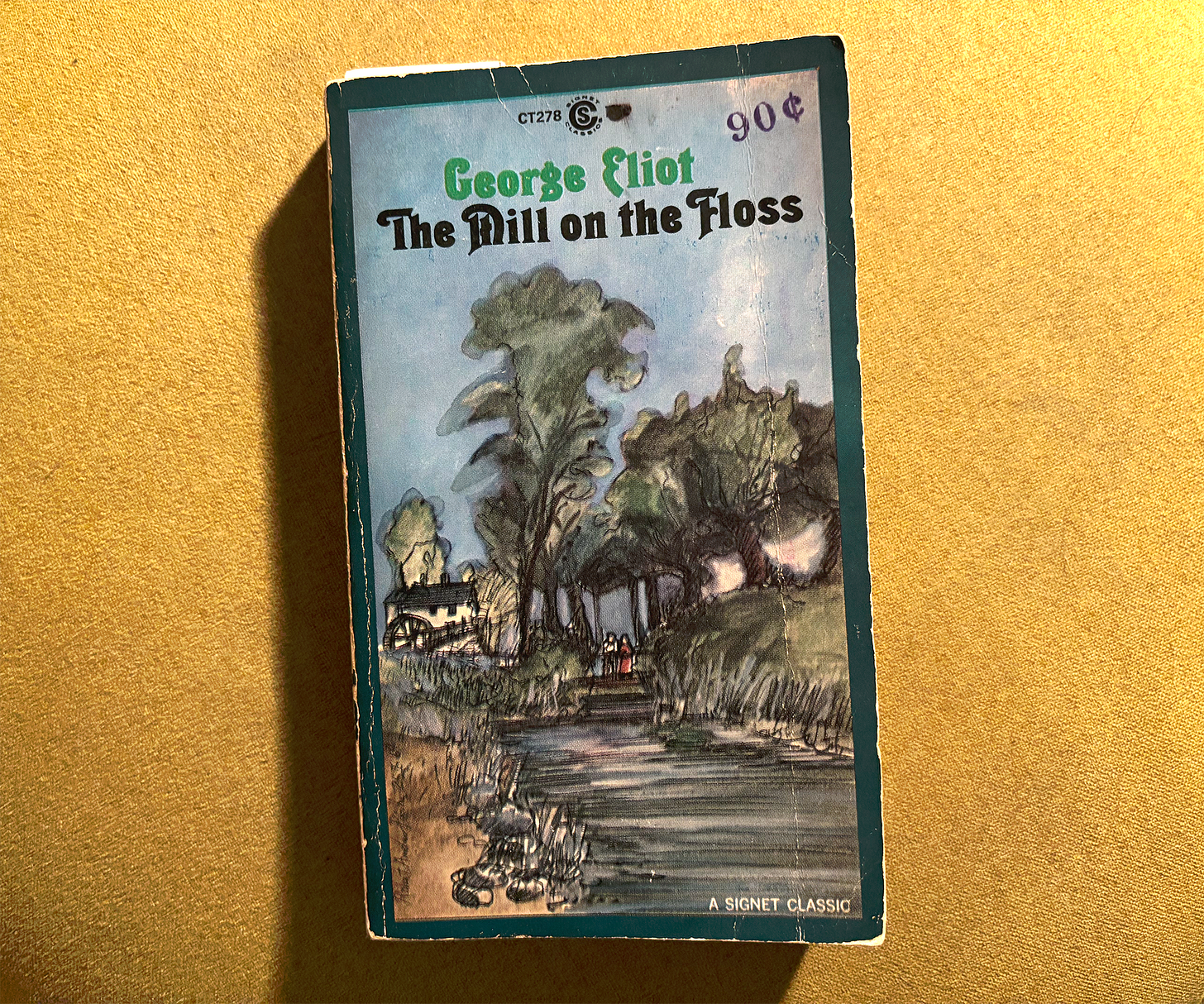

I’m currently about a third of the way through The Mill on the Floss, a novel written five years before Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll’s contemporary George Eliot. So far it is, among other things, a beautifully observed, wistfully sardonic examination of the ways that children’s hopes and emotions grow far more quickly than their ability to navigate their causes and effects. Just this morning, I came across this passage reflecting on the the sensations of Tom Tulliver, the 12ish-year-old miller’s son, returning home after an unpleasant half-year of schooling:

There is no sense of ease like the ease we felt in those scenes where we were born, where objects became dear to us before we had known the labour of choice, and where the outer world seemed only an extension of our own personality; we accepted and loved it as we accepted our own sense of existence and our own limbs. … One’s delight in an elderberry bush overhanging the confused leafage of a hedgerow bank, as a more gladdening sight than the finest cistus or fuchsia spreading itself on the softest undulating turf, is an entirely unjustifiable preference to a nursery-gardener, or to any of those regulated minds who are free from the weakness of any attachment that does not rest on a demonstrable superiority of qualities. And there is no better reason for preferring this elderberry bush than that it stirs an early memory; that it is no novelty in my life, speaking to me merely through my present sensibilities to form and colour, but the long companion of my existence, that wove itself into my joys when joys were vivid.

This goes a way toward illuminating my attachment and awe for the 1985 Alice, a peculiar televised confection that mashed together so much of the world that existed before I was born and left me to puzzle out its mysteries for myself. Freed from “the labour of choice,” its random presence in my life established the need to find pattern and significance in a world I didn’t create. That’s why I cherish it, and so much like it, in all its garish awfulness.

As the safety I was fortunate enough to grow up in recedes with greater velocity into the distance - fueled not just by the inevitability of aging but the rampant dismantling of the society that made my safety possible - I’ve spent a lot of time dwelling on not just the attractions of the past, but the qualities that make them attractive in the first place. I do this for comfort, to be sure, but also to try and get a better handle on who I was then, and what that means for me today. I was happy once, and felt like the world was good - is that still possible now? How can this type of thinking provide solace and relief as we struggle against the nihilism of a world that wants us to be nothing more than products or victims? What use is there in uselessness? In this sense, nostalgia is not automatically a retreat, but can be an earnest striving for understanding the qualities that made life a joy before the oppression of Knowing Too Much.

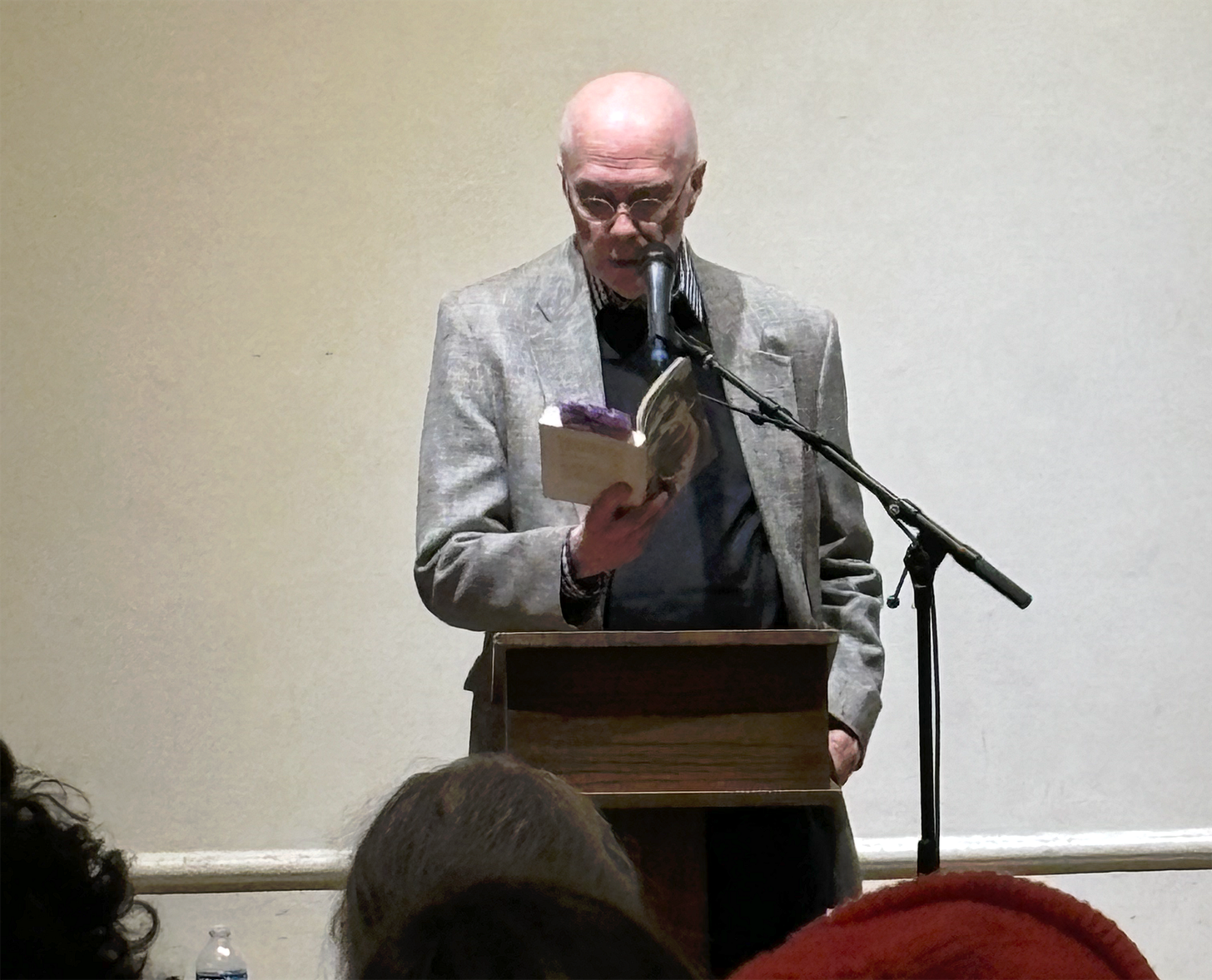

This week I also had the pleasure of attending a reading by the award-winning poet and memoirist Ron Padgett. I was familiar with Padgett as a friend, collaborator, and flame-keeper of the late artist Joe Brainard (who inspired this piece), and I’ve been curious to explore his poetry in a bit more depth. Among other things, I’ve been enjoying a reprint edition of his early collaboration with his fellow poet Ted Berrigan, called Bean Spasms (illustrated by Brainard), which reflects a similar unfettered sense of playfulness in the friendly rivalry of two young minds attempting to top each other’s giddy inventions.

At the reading, Padgett revealed that, even at age 82, he remains keenly aware of the way his early childhood days shaped his adult sensibilities. He spent about half of his reading sharing excerpts from his new memoir Dick, about his childhood friend and poetic peer Dick Gallup (written after similar memoirs about Brainard and Berrigan, all of whom met in Tulsa, Oklahoma during their youth before eventually migrating to New York). The anecdotes he told about his and Gallup’s antics - like stringing a makeshift tin-can telephone across the street between their houses, which got tangled in a car’s hood ornament in the middle of the night - clearly influenced his need to communicate the weird beauty of the world around him.

Poignantly, Padgett read a short poem from his new collection Pink Dust, called “And Where It Lands” (I had to seek this one out on Google Books, so there might be line breaks I can’t see - but he did read it like a prose poem):

When I was ten years old I set up a target in our backyard and from the front yard I shot arrows over the roof. You’d be surprised how quickly a kid can get good at it. This was a skill that later served me well when I faced the challenges of adult life. It helped me never to become a dolt.

The idle attachments of our childhood, in all their arbitrary ridiculousness, help to form us as we grow. Staying curious and continuing to try pointless things - like blind archery, or poetry, or trying to understand the weird artifacts our culture thrusts upon us - keep us connected to our deepest selves. There’s no shame in pleasure, which is one of the fundamental things that makes us human. Yes, we need to fight and strive and help others, but through it all we need to try and retain our lightness of heart - to continue seeing the world through the trustingly uncomprehending eyes of the kid we used to be, who is hungry to learn more while remaining fully immersed in the present moment. Let’s all strive to stay childish, while doing whatever we can not to be dolts.

I loved a series hosted by Shelley Duvall, called Faerie Tale Theatre, on Showtime. She was the executive producer, host & narrator. The first episode featured Robin Williams as the Frog Prince. It ran from 1982-1987, with 27 episodes. I just watched the Frog Prince on youtube, bringing back fond memories of Robin Williams and the series. Thanks for sharing the Alice series. Carol Channing was definitely larger than life. Enjoy 😉

My mother also rued having bought the Betamax! (“A 50/50 shot and I blew it.”) And. I am even now afraid to play the clip of Carol Channing’s transformation.