Look, you know what you’re getting into at this point, so no need to belabor the intro. Alarmingly, this isn’t everything I’ve read over the past month-and-change, but they’re the ones that did the most effective job of poking my brain with a stick. I put them in alphabetical order, because what else would you suggest?

So hey, what have YOU been reading recently? The only thing I like more than reading books is learning about new books I’ll want to read - so what have you got?

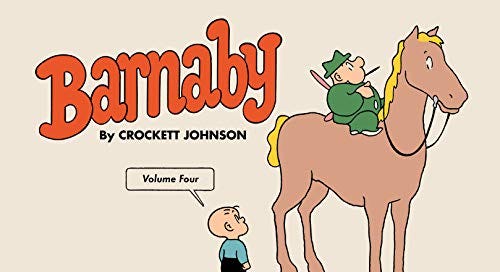

Barnaby, Vol. 4: 1948–1949 by Crockett Johnson

You probably know Crockett Johnson as creator of one of the all-time great children’s books, Harold and the Purple Crayon (though let’s please not talk about the upcoming movie adaptation because I simply can’t and won’t). But his true opus is a daily comic strip called Barnaby that ran for a small but passionate fan base from 1942-1952. The title character is a five-year-old boy indistinguishable from Harold, but its real star is Barnaby’s fairy godfather Mr. O’Malley, possibly the greatest ineffectual blowhard in American literature. With its typed Futura lettering and precision-minted visuals, Barnaby’s visual modernism was supported by antic storylines and wonderfully witty dialogue that make you wish Johnson had also been a playwright (indeed, Barnaby was adapted for the stage multiple times). This is the penultimate volume of Fantagraphic’s five-volume reprint series, which has done important working reviving one of the lost masterpieces of the comic strip form.

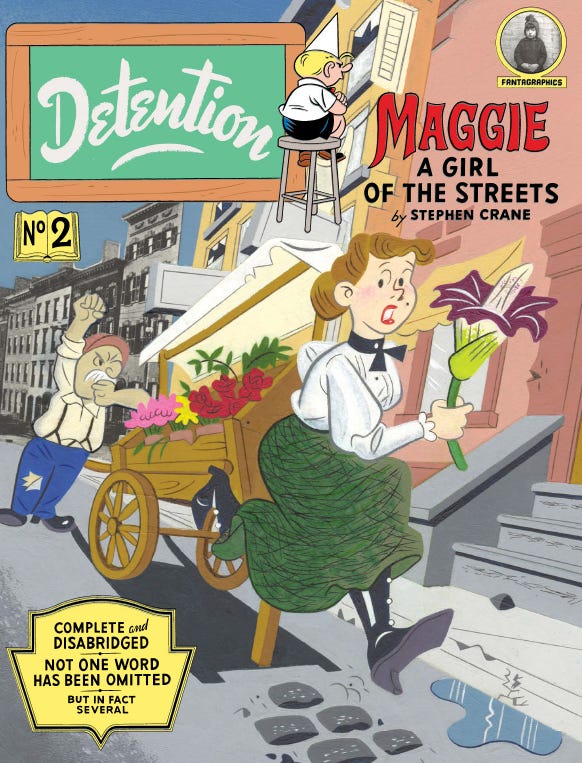

Detention #2 by Tim Hensley

Tim Hensley is a contemporary cartoonist who chews up mid-century comic styles and storytelling only to spit them out in deranged, subversive shapes. His first book, Wally Gropius, is a dada mashup of teen tropes and Bauhaus references; his follow-up, Sir Alfred #3, envisions Alfred Hitchcock as the unlikely star of a kids’ comic strip, in all his controlling, obsessive glory. Detention #2 is simultaneously both more straightforward and more experimental than those previous titles - purporting to be the second issue of a Classics Illustrated-style literary anthology title (there is no Detention #1), it is a comics adaptation of Stephen Crane’s novella Maggie: A Girl of the Streets that gets stranger the more faithful it is to the source material. Characters stolen from Mad Magazine’s Don Martin and the Family Circus enact Crane’s tale about a poor young Bowery woman’s societally-ordained fall from grace with jarring juxtapositions of slapstick and pathos; this is one of those “you’ve got to see it to believe it” kind of things.

In the Freud Archives by Janet Malcolm

Last year I read (and wrote about) Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer, which she was driven to write after getting sued by one of the subjects of this earlier book. I wanted to see how the saga began, and it’s a doozy. In the early ‘80s, Malcolm, who had written a previous book about psychoanalysis, interviewed all of the principals in a scandal of succession around the titular institution, which was created to control access to many of Sigmund Freud’s most important papers. The apostasy at the story’s center threatened to shake the foundations of the field, but Malcolm was more interested in the players’ limitless capacity for self-deception. What makes this book interesting isn’t the Freud stuff per se, but the spectacle of others jockeying for the clout bestowed by his name and reputation as if it were a metaphorically loaded football. Malcolm allows her subjects to ramble on and on, patiently observing as they tie their own nooses to stick their necks through. It’s no wonder one of them sued her - it must be horrifying to see one’s self so naked and defenseless on the page. She won in the end, though - both in court and in the story she told in this book.

Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo

One of the pillars of Mexican literature, Pedro Páramo is a chilling surrealist ghost story about a young man’s search for the rich, brutal father he never met. Considered a progenitor of magic realism (the effusive foreword by Gabriel Garcia Marquez credits it with inspiring his One Hundred Years of Solitude), this modernist classic from 1955 has just been republished in a definitive English translation. Rulfo offers very few signposts in the haunted town where the story takes place - you swim around in his portentous prose wondering who and when you’re reading about, forcing you to pay vivid attention to his hallucinatory images or else go mad yourself. It’s a book where the narrator dies halfway through, a development that has no effect whatsoever on the structure or content of the story. We’re all going to die, Rulfo seems to be saying, so maybe we’re dead already. A short but heavy read, unlike any other.

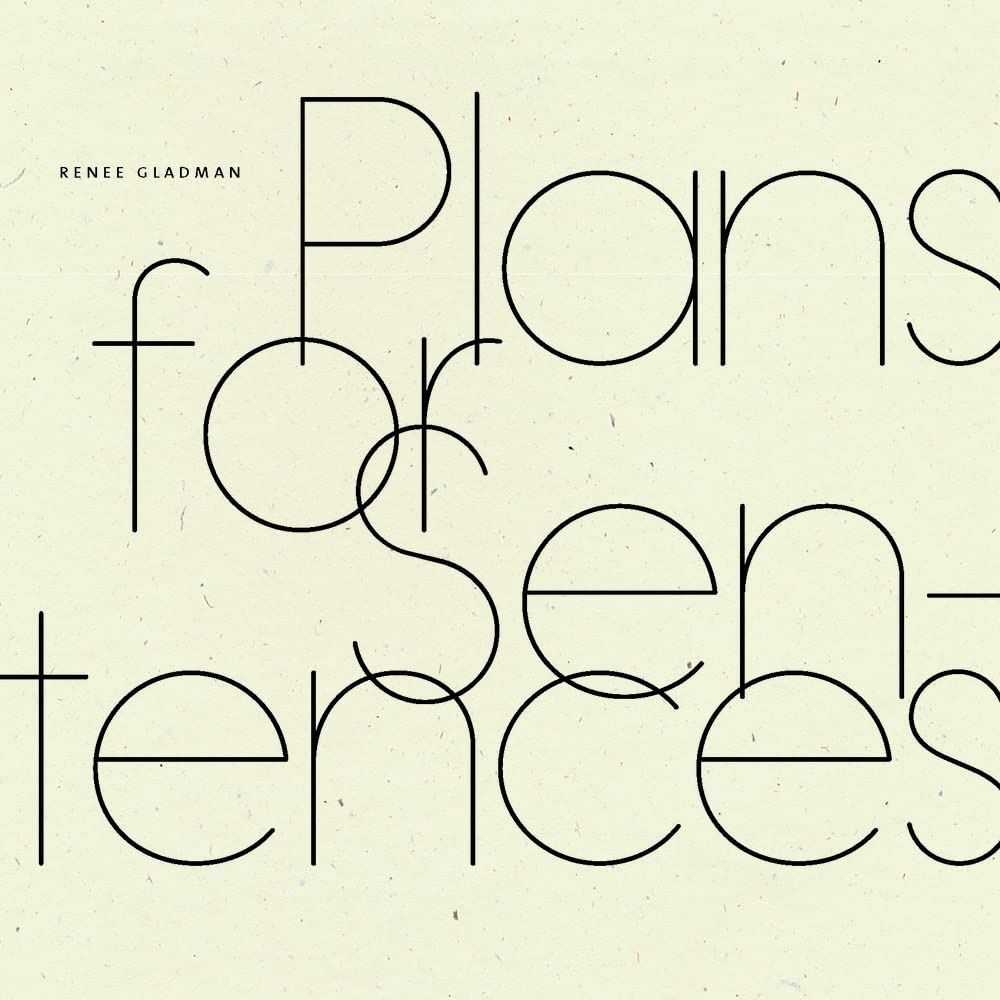

Plans for Sentences by Renee Gladman

Cities and sentences are the same kind of thing: man-made constructions designed to string together bits of meaning. The poet Renee Gladman explores this concept over the course of this book, which is either a long illustrated prose poem or a series of drawings with poems for captions or some harder-to-describe combination of the two. Each left-hand page features scribbles of gibberish cursive that create images akin to maps or blueprints, while the right side features typeset paragraphs that vividly foretell the motions and reactions of a series of as-yet unwritten sentences that may or may not be the ones visualized opposite. Is the text describing the image or the image describing the text? Why not both? Though it all sounds very abstract, this is a work of fascinating graphic and verbal experimentation that casts a unique spell.

Speedboat by Renata Adler

This week, the literary Internet was on fire about a review I haven’t read of a book I have no intention to read, which savaged its author (nothing by whom I’ve ever read) with the accusation that she “clearly wishes to be a person who says brilliant things - the Renata Adler of looking at your phone a lot.” By complete coincidence, last week I read Adler’s experimental 1976 novel Speedboat, which closes the circle by prefiguring the fragmented, insidery, overexposed-yet-impersonal social media world that inspired the quote. The book is a collection of blurbs that never entirely cohere into a storyline - floating images, mean quips that lack a defined target, anecdotes that burst with poignance before leaping headlong into irrelevance. Adler (who, like Janet Malcom, was a longtime staff writer for the New Yorker), savages her own hyperliterary milieu while confidently looking 50 years ahead at the decadence of public discourse. That the book isn’t as disorienting as it must have been when it first came out is its own kind of disturbing.

The War Between the Pitiful Teachers and the Splendid Kids by Stanley Kiesel

Last year a friend suggested that Dash might enjoy this book that he himself had read when he was 12 - he warned me that it was strange, so I smiled and nodded and tracked down a used copy. Then Dash read it and said, “Dad, it’s REALLY strange,” so I nodded and smiled some more and eventually sat down to read it myself. Well, I’m here to tell you that it’s ONE OF THE STRANGEST BOOKS I’VE EVER READ. So yes, the story is exactly what it says in the title: a group of kids at a last-resort middle school for freaks and losers wages war against their cold and uncomprehending teachers. The story starts more or less in the real world, but with each page it descends into a slapstick hellscape equal parts Rabelais and Road Runner. There are megalomaniacal ants, sharks hiding in pools of rice pudding, and an underground series of pneumatic tunnels that suck books from all the world’s libraries, all climaxing in one of the most heartbreakingly equivocal endings I’ve ever encountered in a book for young readers. None of this does it justice. It really is that strange.

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

After putting it off for 15 years, I finally gave in to the literary sensation of 2009. It was really great! If you haven’t read it or encountered the TV miniseries or Broadway adaptation, I’ll remind you that it’s the first installment in a trilogy of books about the rise and fall of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s fixer and enforcer. It’s a narrative dense with historical detail - in this case, all the of machinations leading to Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn and subsequent break with the Catholic Church - but what makes it special is its deep soak in the life and soul of its central character, Cromwell. Mantel makes him such a truly likable guy - cunning yet caring, with a winning sense of humor and a big heart that barely manages to keep up with his astonishing mind - that you eagerly overlook his complete lack of scruples. In this first book, it’s a joy to keep him company on his upward journey, despite the dark clouds that are clearly amassing on the horizon.