The submission deadline for our first issue of slips slips is right around the corner. In the final stretch, I’d like to walk through a few more influences behind this project, in the hope that what excites me will excite you too. My intention had been to take a luxurious full-length soak in each of these publications, but suddenly it’s December, we’re a week away from the deadline, and I’m scrambling to keep up with the pace my earlier self established. Each of these inspirations is worth more time than I can give it right now, but please enjoy these brief glimpses until I can return to them in the future.

THE NEW YORK WORLD

As I hinted in my initial post, the impetus for the form of our first issue of slips slips is the old-school maximalist overdrive of the yellow press of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And there’s no more iconic example of this than Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World - especially the bonkers excess of its Sunday pages.

My primary exposure to the World has been through The World on Sunday, a wonderful, massive book edited by Margaret Brentano and the great Nicholson Baker in 2005. It’s a massive hardcover that reproduces some of the most novel and bizarre examples of the paper in its heyday. For a mainstream paper, some of its experiments in design and illustration feel downright avant-garde.

While the content in these examples can be bold, sensationalistic, and frankly irresponsible, I’m very inspired by the way the information was presented. Every page is a playground that broadcasts an urgent appeal to the widest possible audience - men, women, children, in all parts of the country. For all their boundary-pushing, these pages are clearly meant to be enjoyed, and we hope to bring some of that spirit into slips slips.

THE WHOLE EARTH CATALOG

Launched in 1968, the Whole Earth Catalog served as the Sears, Roebuck & Co. of the hippie era. It was a thoroughly commercial project that attempted to bring capitalism to the level of the counterculture (as opposed to what actually happened, which was the exact opposite) - a kind of underground Amazon connecting self-sufficient consumers with specialist products from around the world. Though there was a physical Whole Earth Trunk Store in the Bay Area, the majority of Catalog listings facilitated direct interaction between hundreds of small businesses and the communes, back-to-the-landers, outcasts, and rejects who needed them to create new forms of community out of the mainstream. But along the way, it turned into something even bigger - a reference volume of the wider world, a pre-internet on paper.

The Whole Earth Catalog’s founder, Steward Brand, named the project after a campaign he’d mounted to persuade NASA to release official photos of the entire globe from space, with the idea that this image would show people we’re all in this together. The contradiction between this lofty communal wish and the publication’s more libertarian strain contributed to Brand’s disillusionment, and despite a series of later supplements and updates, he shut down the main operation in 1971 (though he would continue to publish occasional sequels and supplements over the coming years). As it turned out, Brand went on to become an early Silicon Valley guru, believing that technology could bring around the kind of utopias his compatriots envisioned. (Whoops!) I’m in the middle of reading his biography right now in order to better understand his trajectory and figure out where the egalitarian, DIY promise of the Whole Earth Catalog might still be able to flourish in the tech dystopia that Brand himself played a role in creating.

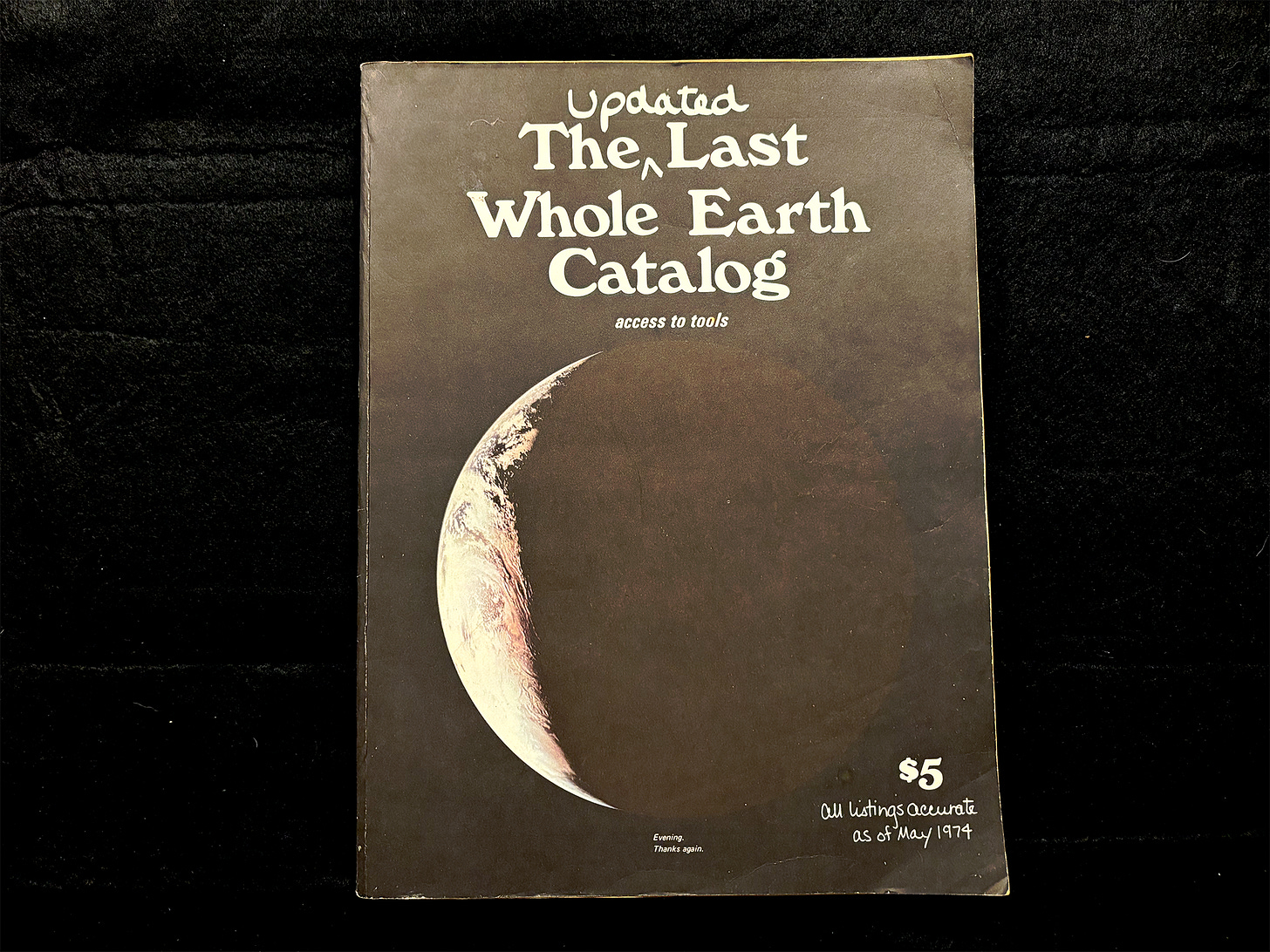

Beyond the purpose and promise of the Catalog, I’ve spent much time poring over some old copies and accompanying books to absorb their evolved version of the stuffed-to-bursting design pioneered by the New York World. Each page is a mosaic of product listings, snarky asides, and talmudic cross-commentary - all filtered through the lens of those attempting to build alternatives to the mainstream. This approach opened the way for a lot of playfulness and innovation; the Last Whole Earth Catalog (1971; these pics are from the 1974 reissue) even features an embedded novel - Divine Right’s Trip, by Gurney Norman - serialized across 450 pages in boxes on the lower right corner of each spread.

There’s so much we can take away from the Whole Earth enterprise. First and foremost, our interest in making slips slips a “community on paper” is a nod to the thousands of people who forged lasting bonds through the Catalog - as merchants, consumers, writers, editors, staff, and readers. While I think we’re more in tune with Brand’s mid-career philosophy (his follow up publication, CoEvolution Quarterly, explicitly took up the theme of our unavoidable interconnectedness), the idea of creating a publication that allows us to circumvent traditional channels is highly appealing. And of course the Catalog’s wonderful, home-grown, shabby-cluttered visual style will live in my heart always.

SEMINA

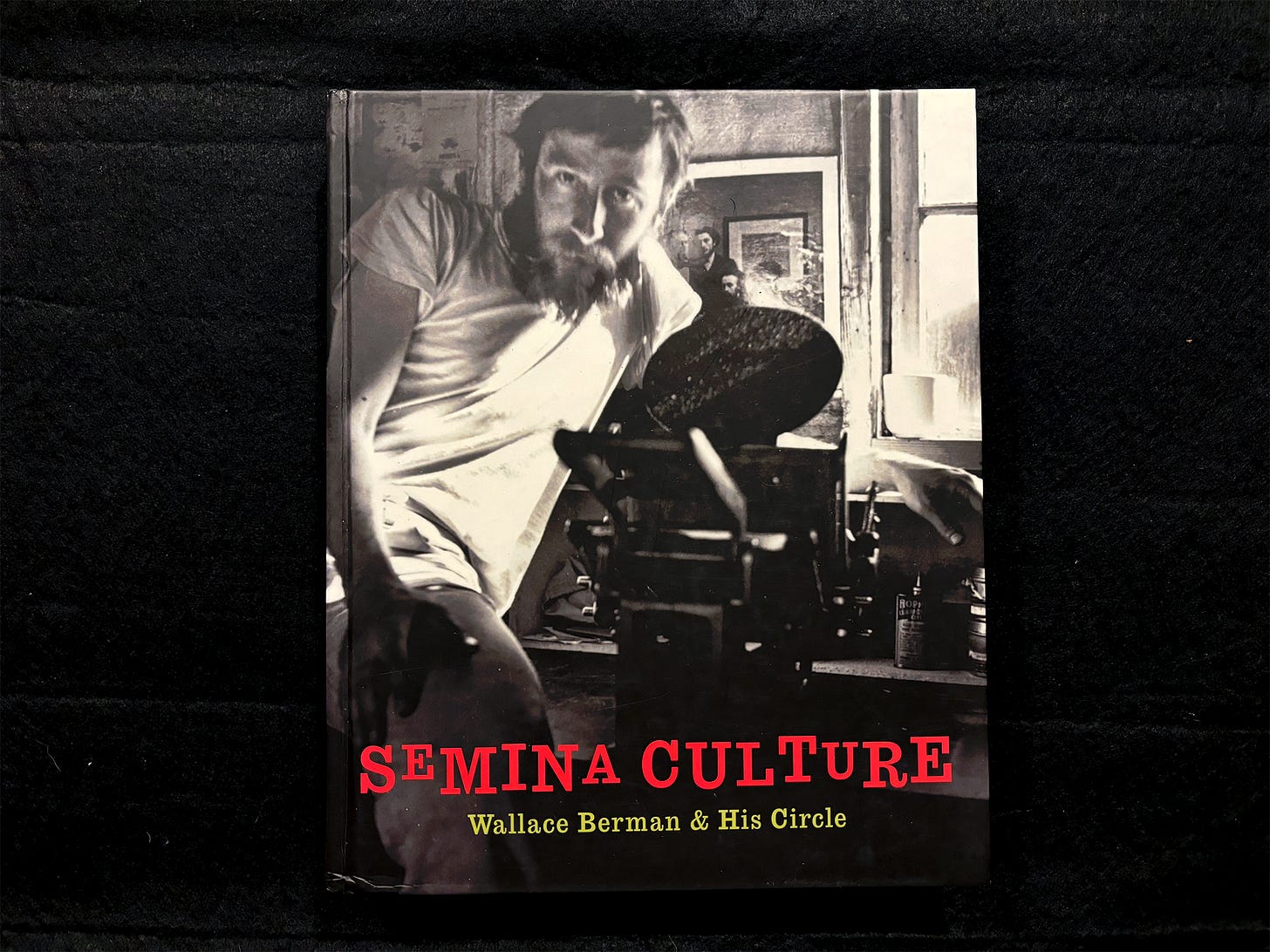

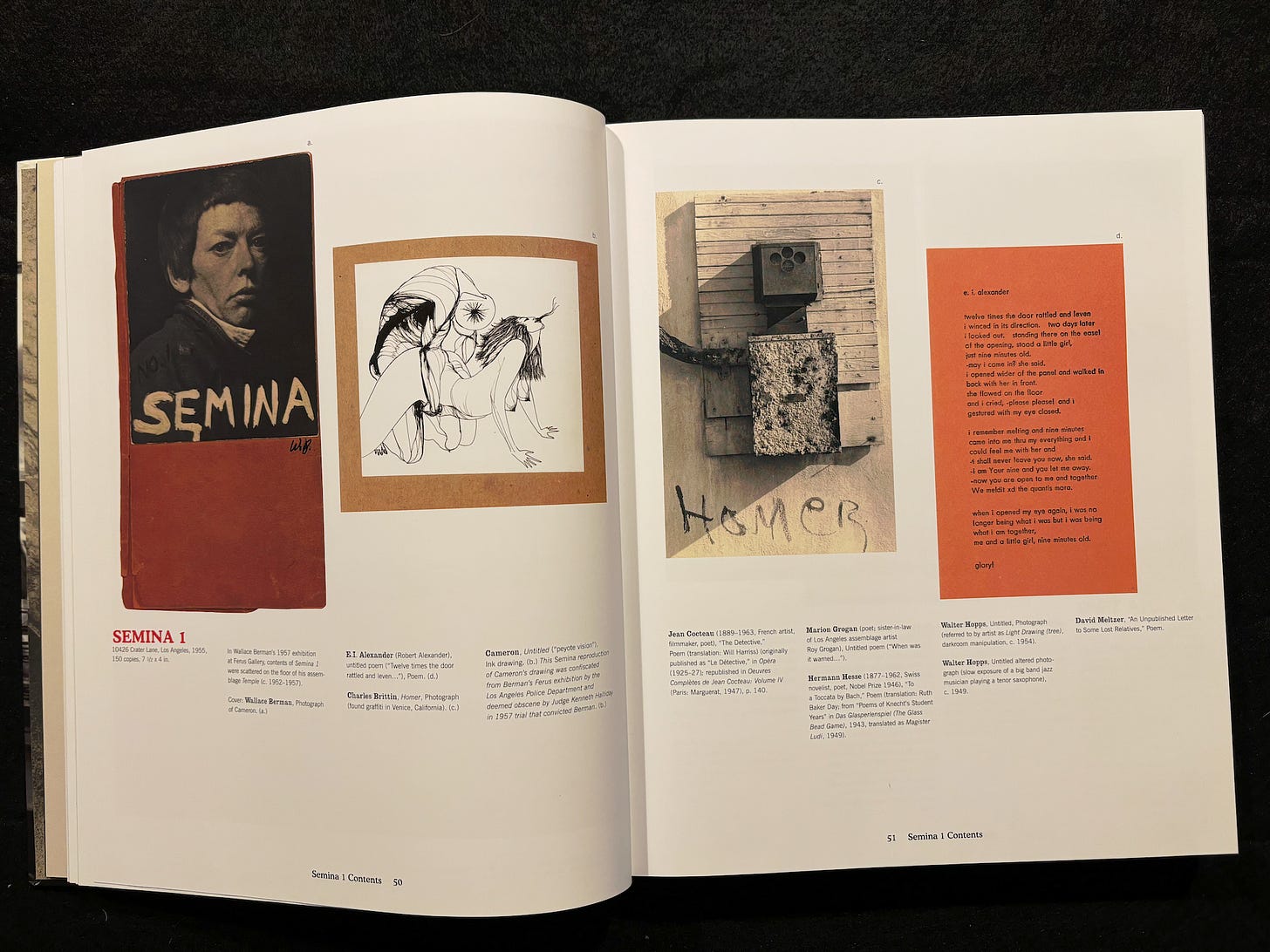

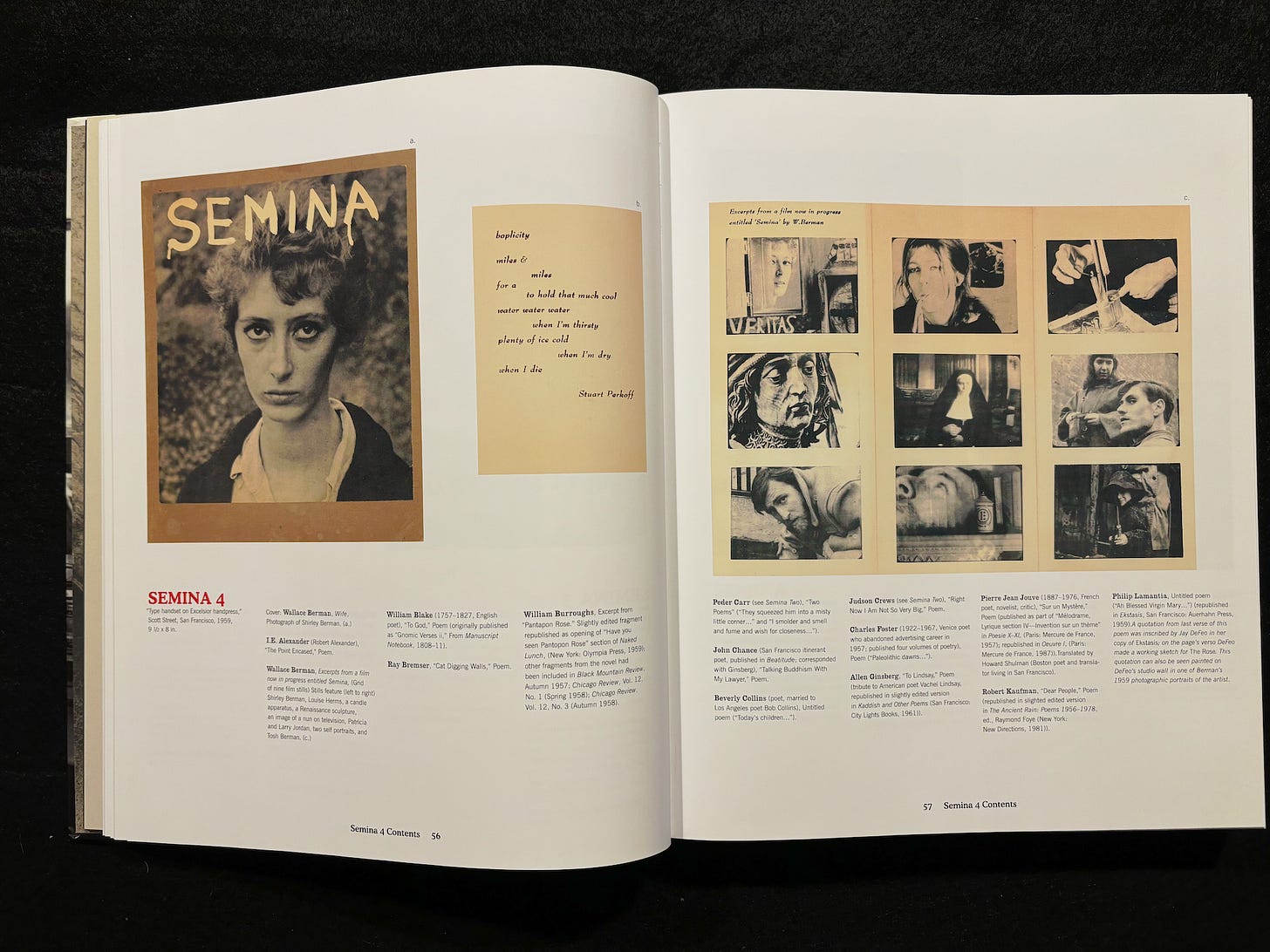

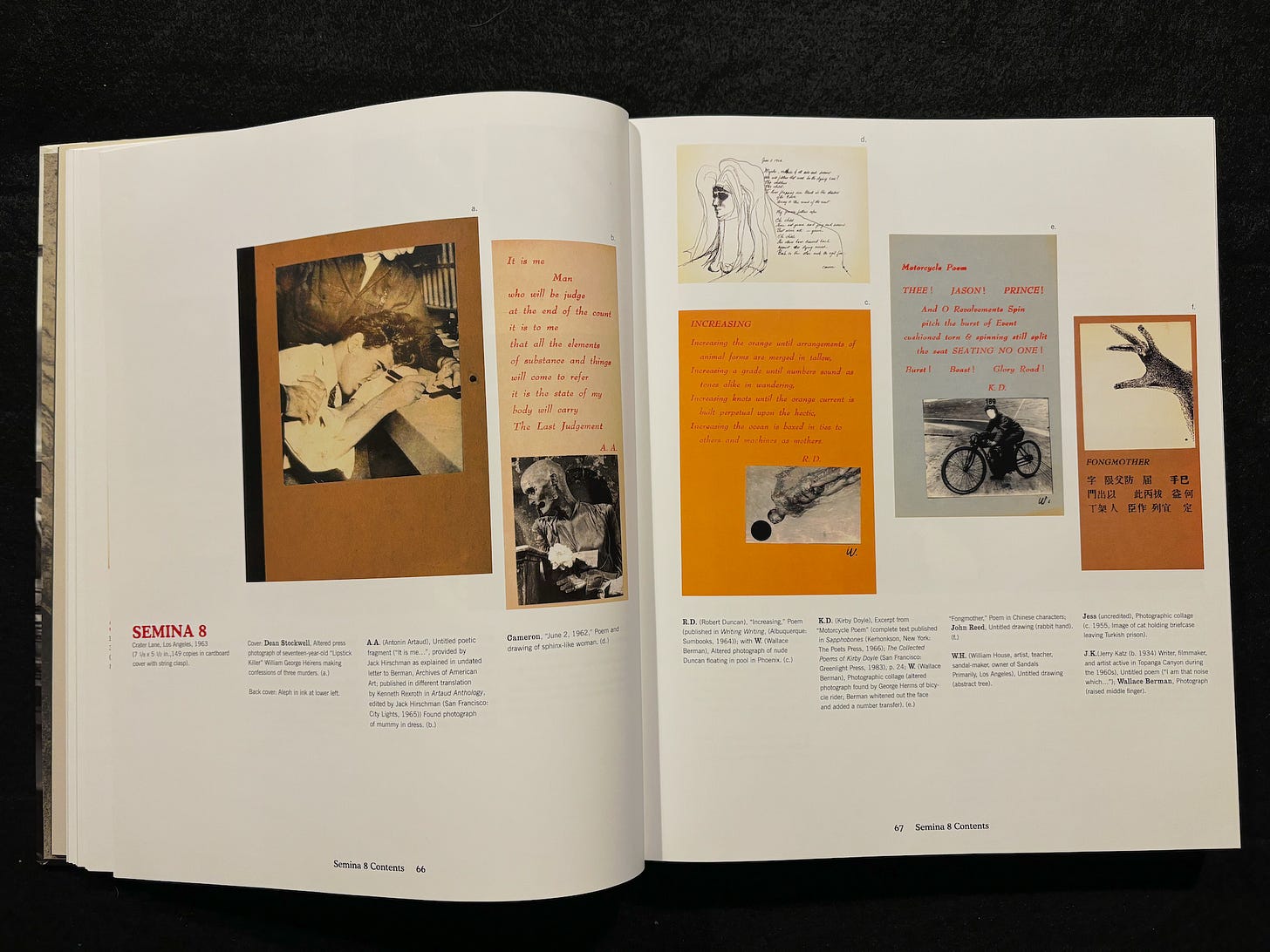

Semina is so legendary as to be almost a dream. Published from 1955 to 1964 by the West Coast Beat artist Wallace Berman, it only lasted nine issues, of at most a couple hundred copies each. Semina was never available for subscription - it came to you because you knew Berman, or because you were a member of the wider bohemian network, or because a series of arcane coincidences brought it to rest on your lap. Semina was a rare cherished gift, and the few copies that still exist go for many thousands of dollars at auction today. (The images here are from a wonderful book called Semina Culture, which catalogues an exhibit about the publication and the many artists who orbited around it.)

While Semina’s spareness is a contrast to the flashy superabundance of the other items on this list, it still reflects an intrepid spirit of exploration. Each issue of Semina took a completely different format. It often arrived as an envelope filled with separate elements - sheets of paper, cards, photos, each with a carefully curated work by a different creator. Some issues consisted only of a single poem and image. Semina came out sporadically, only an issue a year, driven entirely by Berman’s own inscrutable rhythms and interests.

As its title implies, Semina’s most enduring influence was as a seed that sprouted in the minds and work of the many people it touched. These include its contributors and their satellites, including well-known Beats like Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure; artsy Hollywood types like Dennis Hopper and Russ Tamblyn; and trailblazing women artists like Jay DeFeo and Cameron. But equally important are the many small, personal publications that sprung up in later years, inspired by Semina’s ethereal influence. In some ways, Semina was one of the first zines - homemade, highly idiosyncratic, carried around person-to-person and by word of mouth, making a quiet but powerful impact far beyond the organs of mass culture.

In its quiet, grounded minimalism, Semina is worlds away from some of the more boisterous models of the New York World and the Whole Earth Catalog. But I’m endlessly inspired by its purity of intent, its earnest explorations of form and content, its refusal to buckle to the way things are “supposed” to be done, and its deeply personal quality - not only in terms of how it was created, but how it was distributed. Semina plays an almost mystic role in my imagination - the product of serene passions that somehow rise above the fray to provide insight and solace during turbulent times.

THE PAPER SNAKE

If any guy had a claim to being a living publication, it was Ray Johnson. A New York artist whose work came of age in the brief breather between abstract expressionism and pop art, Johnson started his career as a collagist and assemblage artist before veering away from a more traditional route to fame to indulge a prankish interrogation of the ways we communicate.

The Johnson oeuvre is vast and overwhelming, encompassing countless individual “works” that can seem fairly meaningless individually but add up to an astonishing portrait of a restless creative mind. His life was his art, and vice versa - there was no distinction, and it seems that he was pretty much “on” at all times, in every breath and gesture. Ultimately, this approach to his work was so all-encompassing that he ended his own life in 1995 by at age 67 - perhaps it was the only way he could envision any kind of rest.

Despite all this, his career is an uninterrupted stretch of joyous play, almost entirely conducted as collaborations or performances with limited audiences; whatever else his life may have been, it wasn’t conducted in isolation. The strain of work he might be best known for is mail art - the practice of sending a cascading series of small, individual artworks to friends and collaborators via the postal service, a project he referred to as the New York Correspondance School [sic]. When you became the object of Johnson’s attention, the flow of poems, drawings, collages, and other ephemera could apparently become a bit oppressive, but it also made you a player in art history.

Rather than tackling the entire oeuvre, I want to focus on one output of this work. The Paper Snake is a publication of mail art sent by Johnson to artist Dick Higgins, a co-founder of the Fluxus movement, who curated and designed a book showcasing dozens of the pieces as seen through Higgins’ own idiosyncratic eye. The result is a true collaboration, which not only spotlights the weird wonder of Johnson’s work but underlines the complex collaboration between writer and reader, sender and receiver, artist and viewer.

One of the things I find most energizing about Johnson’s work is the idea that any transaction, no matter how small, can yield art - and an accumulation of such gestures can have a wide, unpredictable impact. An artist is not an island, and an audience is not aloof - relationships can activate an exchange of energy through mutual attention and involvement. Sometimes this can happen on small slips of paper, and I find that exciting.

There you go - four exciting publications that are converging in our own modest endeavor before branching out again to influence others - like you? - in strange and unexpected ways.

If you find any of this interesting, do please consider sharing a word or an image or two for slips slips. Deadline is next week, but drop me a line if you need more time - I’m sure we can work something out.

LAST CALL! Here’s a reminder of what we’re looking for:

WHAT IT IS: slips slips is a new literary publication, named for a line from Gertrude Stein, that aspires to build a community of voices on paper. The first issue will be published in early 2025 in a broadsheet format that takes inspiration from the stacked cacophony of 19th-century newspapers, with items laid out in columns across multiple pages that mimic the experience of browsing through an entire world at once.

THEME: The theme of the first issue will be "Dispatches" - in other words, brief, urgent bits of information and insight that desperately need to be shared. These can come in the form of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, drawings, etc. The content is, of course, up to you, provided it conveys the sense of an important message from a world - inner or outer, actual or imaginary - onto which you have a unique perspective.

FOR WRITERS: Please send a submission of no more than 500 words, in any genre, style, or format you prefer. Titles are encouraged but not mandatory and will not count toward the word limit (unless they're super-long).

FOR VISUAL ARTISTS: Please send 1-5 small, black and white images that would reproduce well on newsprint (e.g., not too much delicate detail). These can be either a serial/sequence or stand-alone images - in the case of the latter, we might pepper them throughout the publication rather than running them together, unless you specify otherwise.

NOTE: If submitting poetry or images, please keep in mind that the formatting of each entry in this issue will be in vertical columns - this could affect the positioning of line breaks or drawings.

DEADLINE:Please send us your contribution via email at slipsslipsslipsslips@gmail.comno later than Friday, December 13. We will contact you if we have any concerns or to confirm that your contribution will be included in our premiere issue.